34 pgs/$14

Review by Tricia C. Gonzales

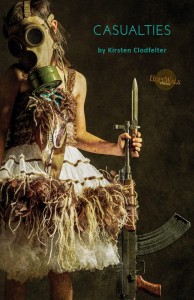

A young military wife anxiously awaits her husband’s return, a motherless teenager seduces/is seduced by her best friend’s Army-enlisted brother, a Kuwaiti-born daughter of a Gulf war vet seeks out her father. These are some of the characters that populate five beautifully written stories in Casualties, the debut collection by Kirsten Clodfelter and first runner up of the 2013 RopeWalk Press Editor’s Chapbook Contest.

Each story in Casualties stands solidly on its own but the way they are grouped together makes the title that connects them that much stronger. “The first casualty when war comes is truth,” the opening pages inform the reader. The stories are told from the distinct voices of the women who are affected as a result of each one’s connection to a man in military service.

In the opening story, “The Silence Here Owns Everything,” we are introduced to Natalie, a teenager learning to navigate the transition from adolescence to adulthood. The titled sections “A Lesson for the Young Cartographer,” “Welcome Home,” “Routines,” “Compensation,” “Two Neatly Labeled Boxes,” “Entropy,” “A Negotiation of Desires” and “A Parting” reveal much about the plot so that, like the main character, we are also “surprised and not surprised” by how the story unfolds and yet we are no less moved to empathy. We are moved because the story is interesting not just for what happens, and we do not read on simply for the plot. We read because Clodfelter has portrayed a believably compelling character in Natalie and we grow to care about her.

“Where Will I Go in Search of Your Safety” and “Homecoming,” the second and third stories, contain some seriously gorgeous prose that will make you want to plagiarize and claim it as your own. “Where Will I Go in Search of Your Safety” has a dream-like quality. The narrator receives a call from someone – possibly her husband, and “as he talks, his faint, uneasy laughter is swallowed by the crackling static.” The static reminds her of the fragility of this moment, “an electromagnetic transmission carrying our voices through a distant satellite.” Often there are long pauses in their conversation where the narrator believes “he’s [forgotten] himself… and is maybe staring down his sadness.” There’s a scripted ending for their call where he tells her he’ll dream of her, that they’ll meet at Otter Creek. Dutifully, she replies, “I’ll wait for you.” What she holds back is that she won’t be seeing him at Otter Creek. “I will never be able to find that place during sleep, that until he comes home — if he comes home — every night I will dream the worst for both of us, as if that will keep him safe.”

“Homecoming” features the same unnamed narrator as in the previous story. It isn’t explicitly stated how much time has passed but it is enough for her to anticipate his return. “I wonder what we’ll do together, the three of us crammed inside these walls trying to figure out how to unbecome strangers,” the narrator wonders. The neologism “unbecome” is simply perfect.

The fourth story, “My American Father,” is told with prose that is careful but not stiff. A young woman born of a Kuwaiti mother and an American father, who is a Veteran of the Persian Gulf war, searches for and confronts him nearly two decades after her birth. Their first meeting happens at a New Jersey bar described as not “crowded or smoky.” The main character has imagined this moment before. She imagines her news wouldn’t shock him; that it would, in fact, be a confirmation of “something he’s felt all along.” She waits at the bar for the right moment to introduce herself and after some time passes she loses her nerve and tries to leave but instead bumps into another bar patron. There is a commotion and she hurries to the door but halfway there, she turns around stands and looks at her father “daring him to know [her].”

Casualties ends with “What Mothers Fear,” a story that opens with a bomb explosion and a panicked mother diving for cover with her infant. The story ends with a sense of uncertainty and this is the right note to strike. “For now, I pull my baby close and rock him against my body like we are adrift at sea, still unsure of where we’re going or if we’ll ever make it there.” Clodfelter holds her readers close as though knowing she will be letting go momentarily and we, the readers, having experienced these stories through her empathetic rendering of compelling characters, have become casualties too.

***

Tricia C. Gonzales studied creative writing at George Mason University, has been published in Peeks and Valleys, A Southern Journal and was a semifinalist in Glimmer Train’s Very Short Fiction Contest. She lives near Washington D.C. with her husband and son where she is a staff writer for a software development company.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)