Books for Precocious Kids and Big-hearted Grownups

~by Dan Pinkerton

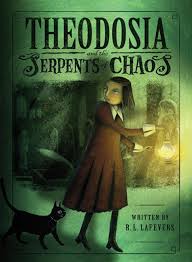

Theodosia and the Serpents of Chaos, by R.L. LaFevers

Like many households, ours is in the midst of a Sherlock kick. I tried explaining to my kids that Sherlock Holmes first appeared back in the nineteenth century, but I think it’s still tough for them to envision him without a cell phone and unlimited free texting. We powered through the current season in a bit of inspired binge viewing and were left afterwards with that pang of emptiness one experiences when forced to bid farewell—even if temporarily—to a beloved TV companion, whether Walter White or the Starks of Winterfell or the rebooted Sherlock Holmes, that “highly-functioning sociopath.”

To fill the void, I suggested we watch the 1985 Barry Levinson film Young Sherlock Holmes, a reimagining of the character as a teenaged student. Penned by Chris Columbus (who would later adapt Harry Potter for the screen), the script stays true to Doyle’s vision of Sherlock. Even as a youth, Holmes’s powers of perception are astute, and during the course of the film he acquires his trademark affectations—the violin, the pipe, the funny hat…even Watson.

My parents took me to see Young Sherlock Holmes when I was ten, and it made quite an impression on me, but in the intervening years I hadn’t re-watched it, so I was curious how the movie (and I) had aged. Inevitably, Young Sherlock Holmes wasn’t as magical as I remembered, but it was still well worth the three-dollar rental fee. My wife spent parts of the movie toying with her phone and clearing the dinner dishes and my six year-old daughter lost interest midway through, but my eight year-old son remained rapt throughout.

You bequeath these artifacts of childhood to your kids with a certain amount of trepidation. It’s a proposal, an invitation, and you worry about being spurned. I felt the same way when introducing my son to Charlie Bucket, Encyclopedia Brown, and Marty McFly. And he has introduced me to Greg Heffley and Captain Underpants, so maybe it’s not a proposal but rather a cross-generational swap. (This is where I thank my dad for Hank Williams, Chet Atkins, and Patsy Cline.)

The villain in Young Sherlock Holmes is set on revenge and has recruited an entire cult to aid in his efforts. The bad guys shoot their targets with darts that induce hallucinations so frightening they compel the victims to self-destruction. These cultists, with their robes and blowguns, seemed more menacing to me as a kid; now they seem slightly silly. The filmmakers expend a lot of energy, and animation, on the hallucinatory scenes, which can likewise either frighten kids (judging from the pillow over my daughter’s head) or prompt giggles from them. Mixed in are some enjoyable but parenthetical scenes that do little to further the plot, one of which involves a school challenge where Sherlock is tasked with recovering a stolen trophy. Other extraneous scenes detail his friendship with an old inventor and his run-ins with Inspector Lestrade. (In Sherlock, Lestrade is very nearly a friend, but in Levinson’s film the inspector primarily views Sherlock as an irritant.)

These disruptions keep the storyline from ever really gelling, and we end up getting a lot of clarifying info via voice-over after the fact. If forced to guess, I’d say the power of the movie for me at age ten derived partly from my infatuation with one of the characters and her subsequent death: in short, a gut reaction that has given way over the years to a more clearheaded approach, which is the danger you run in returning as an adult to books or films you loved as a kid.

The cult in Young Sherlock Holmes originated in Egypt; it is a religious sect dedicated to Osiris, god of the dead. In the film this British fascination with Egypt is touched on fleetingly, but Osiris and Egyptology also popped up in a book I stumbled across not long ago, likewise set in London at around Sherlock’s time. The book, Theodosia and the Serpents of Chaos, was one I bought my son almost randomly. He loved it, and in another of those instances of cultural exchange, I started reading it based on his enthusiasm. Chaos was written by a Californian named R.L. LaFevers. I mention she’s American because it makes her depiction of turn-of-the-century London all the more impressive. Likely she and Theodosia are well-known to readers, and describing the book as though it were some lost relic merely demonstrates my own ignorance of contemporary kids’ lit. Still, for me at least, Chaos was a great discovery.

LaFevers has that writerly knack for evoking a setting—whether a museum, a London street, or an Egyptian tomb—with a few quick strokes. Her prose is lively and vivid, her characters engaging. The heroine, Theodosia, is in some ways the antithesis of Sherlock Holmes. Holmes, announcing the game is afoot, tends to lunge headlong into mysteries, whereas Theodosia is more reticent. Sherlock is a grown man with resources at his disposal; Theodosia is a young girl brushed aside by grown-ups and forced to enlist people willingly or otherwise into her schemes. Sherlock’s talent is his eye for observation, while Theodosia’s is her unique ability to sense the curses that have attached themselves to the Egyptian artifacts her mother collects. (Mom is an interesting character, an American woman who does the traveling and excavating while her husband stays home cataloging the discoveries.)

For all their differences, Theodosia also shares some of Sherlock’s quirks. She’s as sharp as he is, with a preternatural knack for puzzling out Egyptian hieroglyphs and stopping evil spells. When the need arises, she demonstrates a Sherlockian ability to read and manipulate people. Perhaps most crucially she is, like Sherlock, a lonely soul. Sure, he has Watson trailing a couple steps behind but he lives primarily in his own mind, and while Theodosia gathers Sticky Will (a child pickpocket) and her brother Henry into her plan to recover a gem called the Heart of Egypt that has been stolen from the museum, it is Henry who points out her friendlessness to her. Ordinarily Henry is away at boarding school, Theodosia’s mother is in Egypt, and Theodosia’s father is present only in the most cursory way. He’s obsessed with his museum work, leading Theodosia to prepare his meals for him and sleep at night in a stone sarcophagus in one of the museum galleries.

The plot of Chaos moves swiftly. After the stone is stolen, Theodosia, Will, and Henry trail a suspect through the slums of London, where a brutal stabbing ensues. Theodosia meets Lord Wigmere, a kindred spirit who has, like her, dedicated himself to destroying Egyptian curses. He convinces Theodosia she must recover the Heart of Egypt from Count Von Braggenchnot, who intends to put the gem to evil use. After obtaining the Heart of Egypt, Theodosia must return it to the tomb where it was unearthed. This involves stowing away on a ship bound for Egypt and ultimately confronting Von Braggenchnot and his henchmen.

British schoolchildren setting off on adventures is nothing new (see C.S. Lewis, Philip Pullman, et al.), and the genre had a particular resurgence courtesy of J.K. Rowling, but some efforts have been more successful than others. I read the first book in The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place series, for instance, and found it somewhat tepid, with a lot of strange thumps and ominous foreshadowing but not much of a payoff. LaFevers, on the other hand, has created a likeable heroine and a page-turning narrative. Admittedly there are a few familiar elements. Sticky Will speaks and acts as though he arrived directly from a Dickens tale. The comical character names—Theodosia Throckmorton, Nigel Bollingsworth, Count Von Braggenchnot—echo those of Young Sherlock Holmes (Rupert Waxflatter, Chester Cragwitch). And Von Braggenchnot’s plot closely hews to the scheme set forth by the Nazis and Belloq in Raiders of the Lost Ark. In both cases, the Germans believe their artifact will serve as the ultimate weapon, and Von Braggenchnot, like Belloq, has more selfish ulterior motives. Von Braggenchnot’s plot—essentially world chaos—echoes Moriarty’s in the recent Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, though to be fair LaFevers’ book predates the movie. (In a side note, the ritual sacrifice scene in Young Sherlock Holmes closely mimics a similar scene in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which came out a year earlier. Good movies borrow, et cetera.)

If, like mine, your family is looking for ways to fill the Sherlock void, check out Young Sherlock Holmes or Theodosia and the Serpents of Chaos, especially if you’ve got boys at home in the eight to ten year old age range. At the end of Barry Levinson’s film, after the credits, there’s a teaser of things to come when the villain’s identity is finally revealed, but it appears the box office wouldn’t allow for any further school-era Sherlock adventures. The best thing about Theodosia and the Serpents of Chaos? There are sequels!

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)