142 pages, $10.00

Review by Matt Pincus

George Bataille (1897-1962), a prominent French literary figure from the ‘20s to ‘50s, would be rolling over in his grave at the fetishization of pornographic actresses such as Alexis Texas, Rachel Roxx, Tanner Mayes and Teagan Presley. Desire in modern pornography is a parody of itself, as actresses are expected to make eroticism look so intimate and real their viewers forget they’re faking it. Stuart Kendall, the translator of The Little One (1942) and The Tomb of Louis XXX (1947), which together make up the book Louis XXX, writes that “erotica is the activation of desire, its implementation, wherein words, genres, discourses, images and texts, get on top of one another and become sexual.”

The Little One, originally published under the pseudonym Louis Trente, is made up of short, incomplete passages centered on a destruction of self-image. A declarative sentence attempts to affirm the speaker’s identity in reality: “I break the tie that binds me to others.” Soon, identity is split though, as if in a ritual of imagination, similar to the hallucinatory poetics of Rimbaud. The speaker says, “Evil is love. Innocence is the love of sin.” Bataille identifies with the impossible, or rather takes authority symbols such as God and perverts them through images of “a sexagenarian virgin,” also incorporating a brothel. The speaker goes on, in Nietzschean fashion, to say, “there is / only / the impossible / and not God.” The text literally starts to become a reordering, or as the speaker says of evil, “a disorder from the perspective of a different order.” Stuart Kendall mentions Beckett’s Molloy in relation to the text, and the passages are literally illusions produced by the speaker themself, writing out an impossible imagination forbidden to the author.

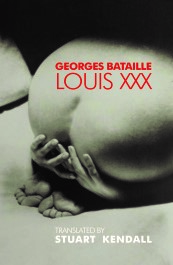

The Tomb of Louis XXX, the title work of the text, is comprised of three short poems: ‘The Oratorio’, ‘The Book’, and ‘Meditation,’ and included two pictures, one of a woman exposing her genitals and the other a mutilated human being burned at the stake. A telling line that brings one back to the infamous Story of the Eye says, “the SKY is inverted in our eyes.” The reader is included to invert themselves when on the following page the sky becomes “the crack” and further, “wound is fresh,” which bleeds until “there is no longer any eye / it’s me.”

The unbounded transcendence or freedom of identity for Bataille is founded in transgression. The woman’s genitals in the photograph become a “laceration” which transgress to an unbounded freedom of the imagination, “wherein I read that which kills me.” Suffering in the photograph of the mutilated human takes on a similar theme, as the speaker meditates on the torture victim, becomes erect, and in a moment “of horror, of light, brought me from the depths to the heights.”

Stuart Kendall’s translation and commentary shows his extensive research and background in studying Bataille, as well as consideration of different drafts and versions of The Little One and The Tomb of Louis XXX floating around for many years. His analysis of Bataille’s pseudonym is especially insightful and eye opening. An obscure work in the history of transgressive literature has, for the first time, been given definitive and due recognition.

***

Matt Pincus was born and raised in San Diego, CA. He received a B.A. in English and World Literature from Pitzer College and is currently an M.F.A. candidate at Naropa University’s Writing and Poetics program. He has a review of Dodie Bellamy’s Cunt Norton forthcoming in Rain Taxi.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)