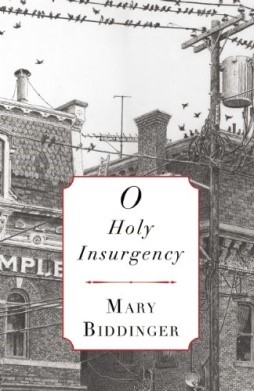

91 pages, $14

Review by Sara Henning

O Holy Insurgency, Mary Biddinger’s second full-length collection of poetry, investigates the trope of love poem within an unrelenting rustbelt backdrop. This universe of desire is not just a savvy reinvention of romance, but a meditation on power in a stifling world. As I read these poems I am reminded of Helene Cixous’ apropos words from “The Scene of the unconscious to the Scene of History”: “at a certain moment for the person who has lost everything, whether that means a being or a country, language becomes the country. One enters the country of words.” Biddinger forfeits her physical tie to a world that fails her with a linguistic soiree of feminine Eros. These candid poems apply hyperbole and tender grit to form at times surreal, at times playful, explorations of lust as it exists in a woman’s body.

The first section, fittingly titled “Anno Domini,” Latin for “in the year of the Lord,” induces reverence in a beloved as one worships in a house of faith. The speaker’s bond is both sacred idol and defense against an underwhelming landscape. The section’s opening poem, “Dyes and Stitchery,” prepares the reader for a psychosocial climate where dogs are designated drivers, children buy cigarettes, and dirt roads are lined by “elbow-high corn.” Yet, here we meet the speaker’ object of affection, and read on as she ignites with him linguistic cataclysms that reverberate through the rest of the book.

These cataclysms confront objects, their excesses, and a need to escape these conditions. Through them, we encounter ecological destruction and blunt complacency. In “Craftsman,” for instance, we are barraged by the images of headless deer the beloved trips over walking across a highway, while in “Prelude to Our Escape,” enraged owls dominate sewers. While all of this roils, the speaker continues to find Capitalist wreckage all around her: “storefronts all cloaked with the same/mirrored plastic” (“Craftsman”), even fields “woven with artificial corn” (“A Gauntlet”). In her city, slaughterhouses and red sequins meld fluidly with rattling bridges (“Metropolis”), yet her lover’s body invigorates in her a site from which she can create a universe from words.

Through withdrawing into a dependence on her beloved’s physical body, a conventionally passive and feminine move, the speaker discovers not only intimacy, but an avenue for linguistic play. In “A Bildungsroman,” the couple is likened to “paper dolls/accidentally printed too close” that “overlap . . . in the most unseemly places.” Actualization of self is actualization of the other, the speaker seems to coo. The small universe of corporeal love, though uncanny and strange, slogs on strongly against an unambiguous, Midwestern horizon that has become its antagonist.

As the first section culminates, the reader is left with a setting that becomes more and more broken. When the chaos threatens to subsume, the lover rescues the speaker as in “Confluence”— “instead of sweeping/ up pieces, you carried me away/to the hill.” It would be foolish to call this move a simple act of codependent-woman-reaches-to-strong-man-for-exodus. Lest we forget, or truly believe the speaker when she gestures, in “Pieces of Myself As a Piece of Red Candy in Your Mouth,” that “[she] would perish within moments unless buried in the crease of your neck.” The speaker searches for a catalyst for transcendence, and finds a lover.

If the first section leads the reader through a speaker’s need for transcendence and a landscape that stifles it, the second section, titled “Ave Verum Corpus,” Latin for “Hail, True Body,” probes the choice the speaker makes to turn to physical love for a solution. What is the true body that lives because of, or outside of faith, the section title seems to ask? For Biddinger’s speaker, it is a body with which to revel unabashedly, a body meant reinvent the world. The poems that follow are hymns to sensuality, bestowing carnal caveats to everything.

For example, in “Genesis,” the lover “invent”s the speaker with his mouth, while the lover begins when he “s[ees] [her] thigh” in a way that gestures mutually Metaphysical carpe diem. As “Incarnation” intones, “Sorrow? And what for?” “Every night we remake us/as our skin transubstantiates.” Every night is another night to defy the world with the body, and discover proofs for not only existence, but empowerment. Yet this is not without an effort that skirts hyperbolic overcompensation. In “A Diorama,” the speaker’s “head/once broke through the bedroom wall” because “nobody/anticipated our vigor.” In “An Excursion:”

some nights we just slammed

ourselves against all doors

in the hotel, screaming our love

is better than your love.

Love is a relentless gesture, the speaker seems to want to tell us. And for the speaker, it is also an auspice, dirty incantation, desperate plea for understanding embodiment. Love is the answer to everything that confuses, abhors, or is strange.

***

Sara Henning is the author of the full-length collection of poetry A Sweeter Water (2013), as well as a chapbook, To Speak of Dahlias (2012). Her poetry, fiction, interviews and book reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in such journals as Willow Springs, Bombay Gin and the Crab Orchard Review.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)