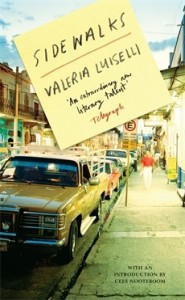

120 pp, $15.95

Review by Jacob Spears

In the essay “Joseph Brodsky’s Room and a Half,” Mexican writer Valeria Luiselli searches out the Russian-American poet’s grave on the island of San Michele in Venice. As she gets lost among the tombstones of other famous artists and writers, she meditates on the futileness of seeking out the burial sites of authors whose work she reveres and the gap that exists between a work and its creator. Her goal of communing with the dead is stymied by an elderly lady who scavenges the graves of people like Brodsky, collecting anything of value some admirer might have left behind. Luiselli feels the fleetingness of her efforts to find the literary in the world, while the elderly woman lets out a cackle, scratches her legs, and is on her way.

Born in Mexico City, Luiselli takes from her experiences as a resident and traveler of cosmopolitan cities to reflect on the author’s place in the twenty-first century metropolis. Like Faces in the Crowd, a novella released simultaneously in the United States, Sidewalks is a collection of essays that imagines a fluid relationship between writers, readers, and the world. If literature does engender readers who wish the world appeared more like art, it also has a history of condemning those who believe the demands of art can be fulfilled by life. In the European literature that has so clearly colored Luiselli’s life as a reader, the most that can be hoped for is to copy what’s already been produced like Flaubert’s Bouvard and Pécuchet. Which is maybe why her attempt to have some graveyard connection with a dead author feels so futile.

Yet, in the second essay, “Flying Home,” Luiselli offers us a way out of endlessly seeking and failing for the world to play out like a story. As she travels across the Atlantic, Luiselli fixates on the tiny projection of the world and the airplane on the screen in front of her. “Those of us who lack patience are condemned to fixing out eyes on the tiny aircraft, as if by staring hard enough we could make it advance a little further.” Like Benjamin in a more technologically advanced age, Luiselli is able to reverse the lens and see the world as a book to waiting to be read. The more the world occurs to us as a representation of lived experience—such as constant real-time feed of our flight on a tiny screen—the more it is the world that demands to be read as if it were something written.

As a result, literature becomes a space for imaginary projection. Both Sidewalks and Faces in the Crowd are interested in the space a story is set in, usually the urban locales of Mexico City and New York City, and how its representation in literature can allow for new spaces that challenge time and identity. “The journeys we make during the reading of a book trace out, in some way, the private spaces we inhabit,” she writes in “Relingos: The Cartography of Empty Spaces.”

A relingo, Luiselli explains, is a term applied to empty spaces in Mexico City’s urban landscape, unplanned absences. For her, relingos become “a sort of depository for possibilities,” the same possibilities literature has. It is not only that habits of reading enable one to “read a city… as you read a book,” but reading a city enables one to read literature as a city, or a space for possibilities to be carved out. It’s here where Luiselli breaks with the French writers who tried to split the experience of literature from that of life, and reveals her affinity with Borges. For Luiselli, like Borges, the continuity between literature and reality is such that, if literature is a process of the imagination, then the world from which art is created is inseparably a part of that dream.

***

Jacob Spears is a writer from Pittsburgh whose work has appeared in Wilderness House Literary Review and Open Letters Monthly. He received his MFA from the University of Pittsburgh.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)