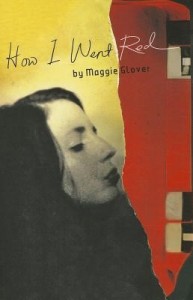

73 pages, $15.95

Review by Molly Sutton Kiefer

The narrator in How I Went Red by Maggie Glover is fierce and unafraid to break wide open, share her intimacies, her scuffed-up linoleum, her junk drawers, her bank bills. This voice comes from the kind of friend you’d crack open a beer with at a late-night kitchen countertop, lean over and tell the secrets of your worst day. This kind of honesty builds a kind of trust for the reader, a take-off-your-coat-and-stay-a-while feeling.

So much of How I Went Red is yearning towards a new start, another envisioning of the self. The poem “In West Virginia” begins: “Each morning was a fresh, blue breakdown.” In “A 350-Pound Man Receives Liposuction on Channel 43,” we observe the gruesome surgical transformation of not only the observed but the observer, ending, “I / was inside / my own skin, upon another bed // of record loss, a home I / made myself of blow-back and skin, inside— / how many hands to make a bed?” Even dreams can refresh the narrator; in “Poem for a Night Shift”: “I fall back into the dream / where I am among the red mountains, / a purple storm flashing: an indulgent ordeal / of color and noise. I awake with the dull impression / that something has happened, somewhere, again—” And then Glover gives us the Amnesia sequence, poems about forgetting to remember again.

At a longer stretch, these poems also explore the concept of loneliness while in reality not physically alone. “Cartographies of Sleep” brings the narrator to Brooklyn to an old friend, where

“We mix mimosas and pathologies.

We make a sign for the fire escape:Like we are kids again.

When she falls asleep in her chair,I take pictures with her phone,

save them under, The Party You Missed.”

Perhaps part of the thesis of How I Went Red can be found in the title “To Come Home Again,” which waterfalls into the line “is to see the rose bushes, wild with their cold fists.” The self in this collection of poems is examining this, what it means to partake in returning, in beauty and harm, in the self—all of these things mingled, separate, at once.

Maggie Glover reveals a bit about the title on her blog:

“When Isaac Newton first divided the color spectrum, he believed that there was a connection between each color and other aspects of the universe. The color red constitutes life (the color of blood), but it also represents solitude because it signifies danger and risk. Its abrasiveness is sometimes off-putting, sometimes arousing – either way, it demands a heaping amount of attention that can be completely exhausting. At the end of the day, sometimes it’s easier to just to leave red the hell alone.”

The multi-part title poem starts as feisty as the description is: “I like to say, ‘I would fuck this city if I could,’ because I can’t.” It shifts, she leaves home, sees a therapist, wears a turtle ring reminiscent of the “tiny dead turtles / scattered around us on the checked tile” of her childhood home, goes home to dye her hair red “all the way down to the root.” This rite-of-passage cycles and recycles, moves what’s not needed down the drain.

Glover gives us all manner of form: we have a poem of couplets, followed by one dashed across the page, then a sonnet dedicated to Marc Jacobs, later still a poem in double column that works when read both across as well as down the page. In these poems, she still maintains a casual tone—her poems peppered with “anyway” and “blah blah blah.” Too, there are found poems using the language of Vogue and poems invoking lyrics. There are some gorgeous images speckled through the manuscript: “the icy hem of snow” and “the hostess hands out small jewels of liquor.” Glover is bold as she brings forth the visceral: a horse’s placenta is “dug at the smell with [the dogs’] paws / and teeth until they found it. // tucking inside their mouths / that which he had hidden in the earth—“ The poems are littered with the discarded, the broken: sneakers, empty cans operating as ashtrays, a handleless pan, a lost key. In “The Garden Party,” the revelers are “still young / and the starlight sticks to us like spray paint.”

One of my favorite poems of the book comes towards the end and is titled “On Recovery.” In it, we are taken to the seventh birthday party of her autistic nephew where he “[enjoys] the grass for hours in bare feet, like I once did / on Ecstasy, rolling in a field until, mud-covered, I told you / ‘This is why people hug.’” There is the thrill at daffodil buds and the birthday cake with “sugar pixels.” She writes, “My sister says it takes him / hours to recover from any emotion” and brings us to this tender and heartbreaking conclusion: “We watch / the video of my sister taking him home after his birth, / and when he cries, she pulls him close, trying to explain: / ‘You were once that small. Once, I could hold you like that.’” The language here is concise, exact. It is what it needs to be. This is the strength of the collection—nothing is over-adorned, each moment well spent, a precise examination in muscular form.

***

Molly Sutton Kiefer is the author of the hybrid essay Nestuary (Ricochet Editions, 2014) and the poetry chapbooks The Recent History of Middle Sand Lake (2010) and City of Bears (2013). She is a founding editor at Tinderbox Poetry Journal and runs Balancing the Tide: Motherhood and the Arts.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)