University of Iowa Press

70 pgs, $18

Review by Molly Sutton Kiefer

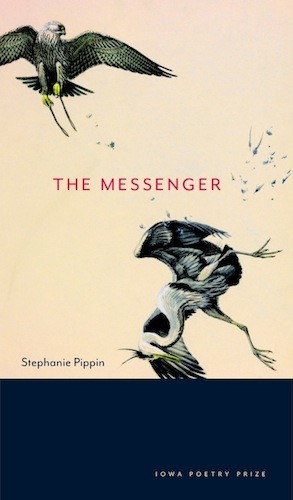

Stephanie Pippin can turn a swoon-worthy phrase. Admittedly, I could spend the whole of my word count copying down the syntactical constructions Pippin created, but I will rein myself in with a few to share: “this sky of promiscuous wings,” “Their jeweled eyes lamp the ash,” “The red fruit, with its buds / Like a string of little time bombs,” “the green / throat of an elm,” “winter’s / blood clock counting / mice,” “The waves in their gray / Ruches remind me / Of tormented pigeons,” “stargazer / lilies wilt like angels / overthrown, a bed of throats / collapsing,” “sogged with August, / morels swelling like lungs.” These images are the sorts I collect, as if an ornithologist in the field, tucking samples into my notebook for the specimen tray at the museum.

Poems with wings: fifteen. Eggs: eight. Feathers: five. The last poem contains all three. Other words I could have counted: blood, death, bones.

Know too, that “his feathers / are holy things” and in a poem such as “Hatch,” “It is hard to give birth / to yourself.”

Pippin’s bird-adorned collection is rooted in her experience volunteering at a local bird sanctuary. In an interview with the Boston Review, Pippin shared, “It required an entirely new (to me) relationship with wildness.” In these poems, there is a calm juxtaposition of the narrator’s experience with a general birdly examination: there is mourning, violence, curiosity, tenderness, and not all at once, but not singularly either.

Directly in line with her volunteerism is the experience of gutting and preparing food in “King Vulture.” She writes of a kind of necessary regret in participation:

” I am sorry for these small

creatures that come to me dead;even as I clean them I turn their heads

away.”

She is fully in her human self as she disembarks the bits of creature, observing the hunger of the vulture and writing, “The rest is routine: I / defend myself as he feigns to eat me. / This is love.”

The following poem, “January,” gives us a kind of enfolding of the narrator with the wild:

” I find [the doe’s] hollow

shape is the form I want

to sink into, pushing

my limbs into hers”

These poems are muscular, only adorned with the image when absolutely illuminating. The poem “Diving Horse,” where “His body is pure screen for the eye / to build its miracles,” ends with the lines

“I love him as I love everything

human that makes me want to fall

and be delivered

headfirst into darkness.”

The boundaries between human and animal are crossed with longing—each still separate, still human and animal. There is an embodiment, but also a shared experience.

The grief elegized is a slender thread we get glimpses of— “your small grave / opened.” And this loss, which seems to be rooted in the human world, is contrasted with the expansive loss in the wilder world, particularly present in her poem “Lone Elk,” based on a herd slaughtered for its land to store weapons of war. In the midst of this poem, we learn “the weight / of the dead is the same / as the weight of the living” and are given images such as “On a table the skull / of a yearling reaches / maturity.” Later, life rises in that field, despite the haunted ground: “Asters rise / like steam from the grass. / A thousand eyes are opening.”

The poem “Homecoming” gives empathy to the cruel acts of the bird:

He is dreaming

children in a phalanx of vultures, their dead

wings hum in his chest when I lay

my ear to it—ragged

gutterals of breath, chest

where the starving

swarm.

Rather than hook the focus on dead children, there is a sympathetic vision of the vultures, showing exactly how we live linked in life-and-death.

The poem “Brazil, 1832,” which inserts phrases from Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle, ends with the lines, “At night I am cut / Free. I confuse myself / With birds.” The narrator never truly seems confused though—longing, yes, but always a separate self, a self that sees the world in color and rich, loamy viscerality. Pippin opens that wild world for the reader in slender, quiet poems lush with both human and aviary desire.

***

Molly Sutton Kiefer is the author of the lyric essay Nestuary (Ricochet Editions, 2014) as well as the poetry chapbooks City of Bears (dancing girl press, 2013) and The Recent History of Middle Sand Lake (Astounding Beauty Ruffian Press, 2010). She is a founding editor of Tinderbox Poetry Journal, is a member of the Caldera Poetry Collective, and runs Balancing the Tide: Motherhood and the Arts | an Interview Project.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)