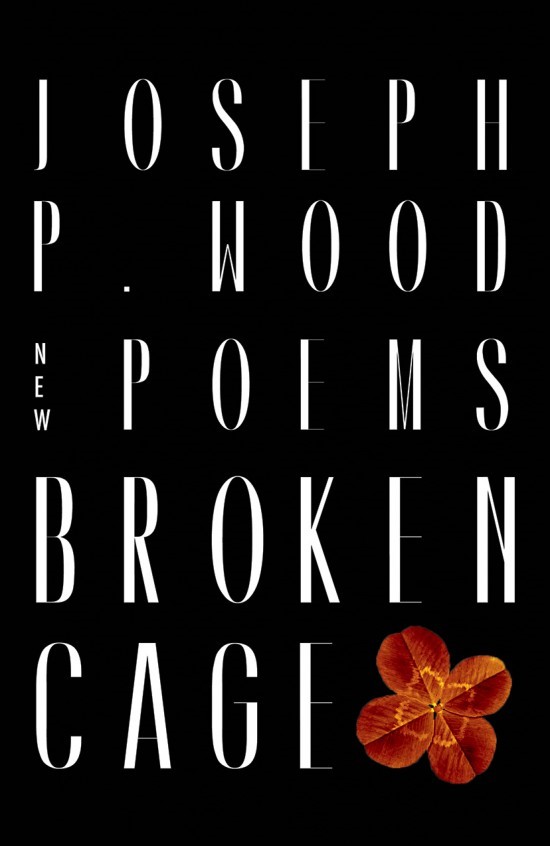

78 pages, $15.95

Review by Anaïs Duplan

Now I the rower gentle on the water. Now I the water gentle / in refraction.

from “Little Schooner”

I can’t help but squeal in excitement whenever I read the first two lines of Joseph P. Wood’s poem, “Little Schooner.” The poem comes late in the collection – it heads the third and final section, Part III: Old-New World – but it’s perhaps the most enthralling poem in Broken Cage, for its music and for its painful sincerity. Nevertheless, while it’s decidedly salient, “Little Schooner” is only as powerful as it is because it lives in the world that the surrounding poems bring into existence.

“Now I the rower gentle on the water.” The speaker, the rower, is alone, as he almost always is. So follows an unrelenting self-scrutiny, which the reader encounters again and again in Broken Cage. For example, in “Of Anxiety,” Wood bombards himself with unanswerable questions. “Joseph, why do you shake like an egg / in quiet, why do you pontificate to the pan / like a wife, why do you hold the pen // shaking Joseph.” He is ruthless here: while one Joseph interrogates, the other Joseph quivers, unable to respond. In “Poor Ex,” the overwhelmed speaker continues to tremble:

My hands shake like boats––tossed on the sea

into which I’m falling––Captain, my pills!––lost

among the inlets––babble-brained––morosely

my hands shake.

The brain appears in many places throughout Broken Cage, and most every time it’s to signal dysfunction and loss. These are expressions of what it is to feel defunct, incapable, and anxious. Yet, just as the infirm brain recurs, so too does the Captain. In moments of turmoil, the speaker calls out to the Captain – as if to show that he’s being directed by some other force, another more powerful figure – the Captain – who as yet, will not answer or help him.

In my many readings through Wood’s third book, I’ve become more and more insistent that every one of the lines in “Little Schooner” has its parallels elsewhere in the collection, and that the poem is itself a microcosmic representation of Broken Cage – and so I include the poem in its entirety:

Now I the rower gentle on the water. Now I the water gentle

in refraction. If this the moon, I befuddled by its light

touch on owls, on feathers, on one bare branch settling

the rower toward stasis. If I drown it will be in my genitals,

that dreary drooping flesh I detest––it put you in hospital

and daughter arrived to this sick, sad world. I was blighted

in my skull’s noxious water. I rowed in circles gently

so as not to incur reflection. The moon insisted on light.

The speaker tries to avoid his own reflection on the water and in this way, prevents two things: first, he avoids seeing himself (which would prompt that terrible self-loathing), and second, he rebuffs his own presence in the world, the sick sad world where “everyone is a patient” (“A Hot Mess”). Broken Cage, perhaps against its will, holds a mirror up to that world, holds a mirror up to itself.

Another sense in which “Little Schooner” speaks to the entire collection is in its music. (In the past few weeks, I’ve found myself going about my day unconsciously repeating that lilting line, “Now I the rower gentle on the water.”) Wood is clearly a fan of the rondeau forms. Part I: Variations on an Innocent Axis is made up largely by the poet’s well-executed triolets. That’s why the explosion into prose in Part II: Broken Cage comes as such a surprise. Whereas the formal concerns of the first section did the work of containing and framing the speaker’s laments, the second section is simply too feral for restraint. “21st Century Pleasantries,” a prose poem detailing an encounter with a friend, is borderline out-of-control. “Gutter Catholic Love Song,” an extended rumination on the speaker’s crisis of faith, moves at a tremendous pace. Imagine a world where Mike Tyson and Jesus are standing side-by-side and the ponies are drunk. It’s an exhilarating, if baffling, world.

Finally, in Part III, it’s as if the two preceding sections have merged. Wood’s formal concerns remain clear, but the incredulity and ruthlessness of his voice have not at all waned. So too, “Little Schooner” shifts in and out of its own prosody, while the tone of voice shifts in and out of adulthood – the omitted articles in the line, “it put you in hospital / and daughter arrived” recall a child’s speech. Nonetheless, the resignation at end of the poem is decidedly retrospective – from the perspective of one who has battled for a long time. The line, “The moon insisted on light” is an almost definite foreshadowing of the world-shattering last line of Broken Cage. But of course, I won’t give that away.

***

Anaïs Duplan is a Haitian-born poet whose work has appeared in or is forthcoming in Transom Journal, BLACKBERRY, Birdfeast, and The Silo. She is a member of the HEIMA artist collective in Seyðisfjörður, Iceland where she hopes to construct a series of spacesuits in the Afrofuturist tradition.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)