$12.00, 68 pages

Review by Rachel Mennies

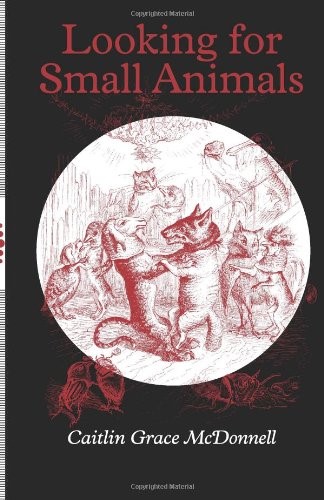

Because it’s the worst place in the world to find the correct answer to anything, and because I never take my own advice, I type one of Looking for Small Animals’ lingering-after-I-finish-the-book subtexts, “Are humans animals?”, into Yahoo Answers. And chris160444, his avatar a growling, wild fox, gives me an answer that I believe McDonnell might echo: “The worst animals on the planet,” my new friend chris says, “are humans.”

The tameless, yet complicated animals inside us come alive early in Looking for Small Animals: “The animal started lashing at fifteen,” the speaker of McDonnell’s poem “The Moth” tells us. We read this collection, McDonnell’s first, to see where the animal leads us: to understand what an at-times-savage, at-times-peaceful human speaker can teach us about a world gone machine, about our distances from and connection to our nonhuman co-citizens.

At the intersection of our animal and human worlds lie some of the most powerful poems in this collection. “Sleeping with Emily Dickinson” imagines the poet as the speaker’s sort-of-teenage-bestie, sort-of-pet, with the speaker declaring her intentions at the outset: “I would sneak in through the window, / bring her sweet meat.” And in “The Mice,” the speaker imagines her parents’ marriage as “small animals?/ hidden in cupboards,?/ among papers stuffed in drawers, / in the food.” In these poems, the animal sneaks into our human selves, revealing our instincts and desires. Here, we confront our animal selves most frequently when we slip into our unconscious: as in dreams, where most of this collection’s animals surface and wander. “Stiff family of?/ chairs thinking in the / bright dark,” considers the poem “Blue Mountain,” “Wild boars in your dream / nudging the fence.”

In considering this animal/human connection, Looking for Small Animals employs a sly prosody, making use of repurposed and nonce forms to heighten the stakes of the collection’s “feral” poems. The unconventionally-formed “Feral Ghazal” considers the radical juxtaposition of nature and technology and, as do many of the collection’s poems, invokes the author by name:

In a basement in California, a woman sleeps cradling a phone.

The heightening of one sense necessitates diminution of the others.

All change begins with disruption.

The process of one animal taming another is both violent and loving.

And you, Caitlin, what will it take to hold you still…

Here and elsewhere in the collection, California becomes a place both wildly natural and overwrought by human change—and the speaker’s positioning in that landscape, as she navigates “natural” forces of illness and “human” forces of divorce, among others, grows increasingly compromised. Other poems, like the sonnet “As of Now,” make use of a more straightforward formal tack, but grant the reader access to the same wild, curious speaker: “You must learn listening. Not just to / small animals tucked in crevices?/ in cupboards and bodies. // But to strange, misguided arrows / that climb you mountains rather / than glowing lazily in still ponds.”

As with form, McDonnell also plays with our expectations of the speaker’s voice in the collection’s poems—here, a sort of writing-process metanarrative rules the day, as McDonnell pulls back the curtain on how a poem comes together, showing its complicated journeys. “Form and Content” most overtly takes us through this process, with the speaker declaring at its outset that

This poem has an anonymous woman in it.

It is going to make you watch the birds peck out her eyes.

It will so convince you of the grief of the world,

you will actually enjoy the way the birds eat at the woman.

By anticipating the reader’s reaction, “Form and Content” becomes both poem and its metabolism, giving the reader a sort-of-mirror, sort-of-window into their interpretations of the work against the speaker’s. McDonnell employs this process-metanarrative approach elsewhere, as in the poem “Letter to Teacher,” where McDonnell foregrounds these moves as writing advice, elegizing a former teacher who gives her advice on the very poem unfolding before the reader:

(And here you’d tell me to give more information.

We’re not mind readers, and we’re probably more

ignorant than you fear we might be.)And no, you wouldn’t suggest

I come right out and say it,

but the father needs at least to

make an appearance…

Here, we meet the strangely visible animal bones of the writing process-in-progress. We see the risks the speaker admits to taking as she elegizes her former teacher in verse. There’s the risk of writing wrong; the risk of remembering wrong, or of depicting something somehow inauthentic, in elegy, to the original person or experience, “because that would be wrong, to pretend seduction / wasn’t part of the process // of attaining truth, tangled in a golden mesh.” There’s risk in showing the reader how the writer writes; there’s also reward, however primal, in resonating loss outward as McDonnell does in these elegies, in gathering the experience in all its misremembered moments for the reader and presenting them in the righteous jumble of drafting.

If my Yahoo buddy chris is right—if we humans are indeed the “worst animals”—then Looking for Small Animals complicates this position in a welcome and challenging way. It grants us a glimpse into the deep complexities of human grief and loss, and considers our relationship to the rest of the “kingdom” with one eye toward criticism and another toward concord. If we humans are the worst animals, then Looking for Small Animals could serve as our instruction manual for betterness; its wild poem-communions could maybe even bring us part of our absolution, as we come to understand our own animalness and to see with new eyes the animals among us.

***

Rachel Mennies is the author of The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards, winner of the Walt McDonald First-Book Prize in Poetry, and the chapbook No Silence in the Fields. Her poems have appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Journal, Poet Lore, and other literary journals, and have been reprinted at Poetry Daily.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)