150 pgs, $16.95

Reviewed by Jonathan Russell Clark

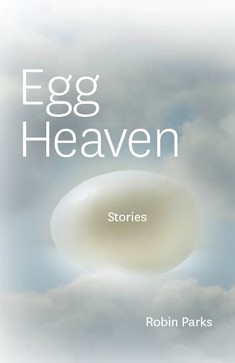

Diners provide the interconnection for the characters in Robin Parks’s fine debut collection Egg Heaven. All set in Southern California, the servers at these establishments move in and out of each other’s lives like their customers move in and out of the restaurants themselves. In “La Playa,” young Bell, after losing her mother and her home, finds employment in the titular diner. Later, in “Delgado’s Family Mexican Restaurant,” we hear of “Jacinto’s Aunt Bell’s restaurant, La Playa,” giving us a sense of what happened after Bell’s story ended. Young Bell, again in “La Playa,” tries to eat at a place called, simply, Breakfast, but “the waitress sat in the back, smoking in the dark, ignoring Bell, so she finally left.” In another story, “Breakfast,” we seem to meet that neglectful waitress.

But these connections are not meant to further the plot. This isn’t a novel-in-stories; it is a collection of interconnected stories. The distinction is important here because Parks isn’t interested in telling one big story but a number of small ones. The autonomy of each piece is necessary for the larger, more important connections to take hold. These characters––these servers and owners, customers and regulars––are linked less by the coincidence of geography and more by the state of their lives––full of loss, fragile hope and fleeting tenderness.

In “Home on the Range,” young Penny boards a bus from California to New York, leaving behind Al, the owner of the restaurant where she worked. In “Los Golondrinas,” Toby and her father Ed try to cope with yet another desertion from Toby’s mother. As noted, Bell of “La Playa” lost her mother, too. Clara, in “Egg Heaven,” still grieves after the death of her twin sister Sara. Their aches follow them, color the language of the prose, so that everything becomes steeped in a quiet, nearly indecipherable sadness, like a stranger’s face, full of suggestive meaning just beyond our reach. “My mother had schizophrenia and perfect pitch,” Laura tells us in “Breakfast,” and she considers what this might mean:

She’d call out “G” when the phone rang, “F” at the doorbell. As I clumsily, slowly, begin the prelude’s arpeggio down the keyboard, like so many drops of rain on a lonely night, I try to remember if this piano––her piano––was always weak in its pitch, and if so, was this what drove her mad, knowing the way she did what constituted a perfect sound?

These are the kinds of questions mourners ask, and Parks, in story after story, gracefully and beautifully taps into the heart of her characters.

To read these stories is to be renewed, as Parks is unafraid to grant her characters some reprieve, some actual happiness, in the end. Contemporary short stories thrive on sudden moments of violence, or the suggested menace of malice, or the tiny, pivotal moment that ends a relationship. Parks is interested in something different, something more humane. In “Egg Heaven,” Vince, a war vet and a sketch artist, yearns for Clara, the haunted waitress. The two share such delicate sensibilities, one can’t help but root for them. But since “Egg Heaven” is a contemporary short story, I dreaded the moment where their union would prove impossible, tragically inches from their reach. But Parks dares––and I use that verb very deliberately, for it is daring––to put them together, albeit tentatively, carefully:

Vince brought Clara’s hands to his lips, kissed each fingertip. They sat curled into each others’ arms until the bell over the door of Egg Heaven began to chime. Customers filled their regular spots and waited patiently for their eggs.

Restaurants are often improvised families, created, often, because each member lacks in various ways the intimacy family provides. Parks’ women––as most of her protagonists are women––seem to both languish and thrive in these environments. They yearn to escape as much as they yearn for a home, for some connection to a sturdy point in the universe. When Zappa points out La Playa to Sunny in the book’s final story, “Floating By,” she says, “I used to work there…My boss was my best friend for a while. Her name was Bell. Isn’t that pretty? She was older, too.” Everything in Egg Heaven culminates to this line––the connections these women share, and the ones they don’t share; the passing of time, so cruelly casual; the temporary comfort we seek that soon becomes permanent––and through a mere 150 pages, Parks has given us the foundation for memories. We know Bell by this point, and it’s a wistful experience to read of her continued life from others. Like the restaurants in these stories, Parks has created, for us, an improvised family, in all its tenuous glory.

Egg Heaven is the first book from Shade Mountain Press, a publisher that aims to end the imbalance of women in the literary world. Parks’ collection is a wonderful way to start such a noble and necessary project, as Parks is a stunningly gifted writer, one whose careful optimism and tender sympathies seem to be, like her characters’, hard won––and all the more meaningful for being so.

***

Jonathan Russell Clark is a regular contributor to The Millions, PANK, and Slant Magazine, and his work has also appeared in The Georgia Review, The Rumpus, Colorado Review, Chautauqua, Thrasher Magazine and elsewhere. He is currently at work on a novel.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)