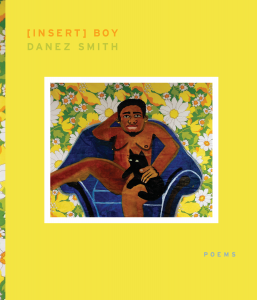

116 pages, $16

Review by Peter LaBerge

“Being black, holy, drunk, my mother’s son”

Thank God for good poetry. Thank God for good poetry collections that leave necessary emotion in their wake, and thank God for poets like Danez Smith, who—through his debut Lambda Literary Award-winning poetry collection [insert] boy—demonstrates that what is political should be openly approached in personal terms, and vice versa. In [insert] boy, Smith ignites a discussion about life as a queer person of color in today’s racially charged, orientation conscious society. Through the arteries of movement, music, and religious (or non-religious) experience, Smith allows us to imagine life from his perspective in a way that only the most powerfully evocative poetry can.

The collection begins simply enough. In the opening poem “Black Boy Be,” Smith compiles a list of similes that complete the sentence “Black boy be _________.” We meet a character who ranges in manifestation from “a village ablaze” to “an ocean hid behind a grain of sand” to “blood all over everything.” Within the first few lines, we effectively meet a character who represents the world. Ultimately, we come to find this sense of motion informs many of the poems in the collection. In the first “Poem in which One Black Man Holds Another,” “the black boy falls into himself / & you mourn everyone ever.” In the third poem of the sequence, the narrator “make[s] fire in the absence of storm.” In “The Black Boy & The Bullet,” “one’s whole life is a flash.” By emphasizing the fast-paced, always static nature of his narrator, Smith enhances the experience of [insert] boy’s reader by reinforcing both the urgency of his message as well as the entrancingly violent quality of the events that transpire.

Similarly, the presence of music seems to correlate with the narrator’s control over and ownership of his body. In “King the Color of Space, Tower of Molasses & Marrow,” the body quite literally becomes music—the poem begins, “I hear music rise off your skin. Each hair on your arm a tiny viola…” We also bear witness to the power of music to connect two separate bodies, as “I sing / this man in my bed all night, my mouth a loose choir / & his body a gospel…” As Smith leads us to later poems, music seems to acquire significance with regard to his relationship with God and religion. One of many examples of Smith’s approach lies in his poem “Song of the Wreckage: [So me & the boys ride out to smoke].” Smith writes:

…If there is a (or in spite of?) God

let my small brown lips know their full brown lips before I rotlet us slow dance in the moonlight &, later, from behind

let us sway until we fade into a brown & endless light.

By “slow danc[ing] in the moonlight” whether “there is a … God” or not, Smith liberates himself (and, with any hope, queer readers) from centuries of self-doubt, self-hatred, social influence and internal/external racism & homophobia in the span of one four-line stanza on the subject.

In fact, throughout the collection, Smith establishes his God character as refreshingly flawed. To Smith, God is a man who makes bets with the Devil only to see “[He] is too drunk to see that he’s down” (“Song of the Wreckage: [I’ll trouble the black corpse water…]”); God is an essence who inhabits only “in the saltiest parts of men” (“On Grace”). In fact, in his poem “Craigslist Hook-Ups,” Smith brings his “daddy”s into conversation, writing, “forgive me father for I have called another man daddy.” Through his artful merging of “daddy” roles with varying levels of masculinity, Smith not only expands his poetry to deeper critical and social appreciation, but also lends credibility to broadened conceptions of what a man (particularly a queer man, and even more particularly a queer man of color) can be.

By its very structure, [insert] boy offers a chilling glimpse of the subtle yet largely accepted social norms that perpetuate problematic aspects of the society in which we live. After all, who facilitates the change in how we refer to the narrator, and who determines the lens through which we view him? Certainly not the narrator himself; it is Smith, with each of six section headers meant to be inserted into the title—first black, followed by papa’s lil’, ruined, rent, lover, and again. By establishing a world in which the narrator simultaneously cannot control how he is portrayed and must continually either overlook or submit to the various discrepancies between his identities, Smith makes a powerful statement about the “battle nobody ever named / more than struggle”—living outside the problematically authoritative realm of whiteness in the Western world (“For Black Boys”). With any luck, his message will be here to stay.

***

Peter LaBerge’s recent poems and reviews appear in Beloit Poetry Journal, The Iowa Review, Best New Poets 2014, The Southeast Review, Sixth Finch, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and Indiana Review, as a finalist for the 2015 Indiana Review Poetry Prize. He is the recipient of a fellowship from the Bucknell University Stadler Center for Poetry, the founder and editor-in-chief of The Adroit Journal, and an undergraduate student at the University of Pennsylvania. For more, visitwww.peterlaberge.com.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)