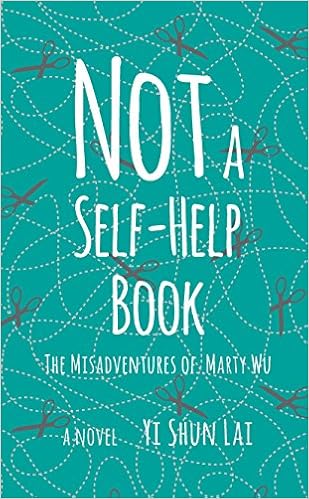

Shade Mountain Press

218 pages

Released May 6, 2016

REVIEW BY MELISSA OLIVEIRA

—

As long as we suspect we’re falling short in some area of our lives, there’s really no end to the books we will buy to try to improve: a 2014 article I read stated that self-improvement was “a $10 billion per year industry in the U.S. alone.” As it turns out, when it comes to solving the problem of ourselves, we have very deep pockets — and solving herself is exactly what Marty, the smart but hapless narrator of Yi Shun Lai’s wonderful new novel, Not A Self-Help Book: The Misadventures of Marty Wu, seems on a quest to do.

From the outside, twentysomething Marty Wu appears to be doing pretty well. She moved to New York from Taiwan when she was five, and when the novel opens she has a job in Manhattan working in advertising sales for a magazine. Unlike her previous job as an illustrator, advertising sales isn’t a line of work that particularly excites Marty. Still, she appears to be good at it: the early pages of the novel find her on the verge of closing a deal that promises a fat bonus check.

Yet Marty, whose story comes to us in the form of a diary she began on the advice of a self-help book, is someone we come to know intimately, and all is not perfect in Marty’s world. We know, for example, that her fascination with self-help books borders on an obsession born of insecurity. Each interpersonal interaction and emotional reaction is noted carefully in the pages of this diary and compared to an ideal version that she might have read, say, in The Language of Paying Attention to YOU or a similar user’s guide to life. We also know that advertising sales is a poor fit for this vibrant and creative young woman, and that the aforementioned bonus check is a potential way out of the gig. Alone at her desk, she listens to fashion and design podcasts, and daydreams about investing her windfall into a little storefront: the type of warm and intimate costume boutique that would, she hopes, allow clients to “slip into another skin” for a time.

But Marty is our heroine, and as she says herself, “I think somewhere in one of my books it says that I must be a Protagonist, like characters in novels. Protagging is hard. Characters in novels never have it easy.” Yi Shun Lai, for her part, pulls no punches with Marty. Rather, as Lai steers Marty into increasingly uncomfortable and painful situations, Lai writes with an incisive humor and a light, chatty tone that often had me laughing aloud as I read.

While this was one of the funniest books I’ve had the pleasure of reading in a while, though, it isn’t all laughs. Marty, we understand, has a serious longing to go after what really matters to her, but she is hobbled by variety of obstacles — the very challenges that made her such an avid consumer of self-help books in the first place. The promise of such books, after all, is one of hope — hope that Marty might finally learn how to be a better leader, colleague, saleswoman, daughter, person. Since there are no guides for learning simply to be a better, stronger Marty, our narrator flails. She searches relentlessly for advice from people and books that are so distant from the reality of her life and relationships.

This brings us to Marty’s relationship with her mother. Mama excels at cutting Marty down: thoroughly, efficiently, and often while switching in rapid succession between English and Taiwanese. “I double-step,” Marty writes when meet Mama for the first time, “trying to move quickly, and trip. ‘Sloppy,’ says my mother, only in Taiwanese it sounds like more than that, like you haven’t just tripped, but that you’re a tripping, drooling shadow of a functioning creature.” Watching Marty endure what she does is often heart-wrenching, and we aren’t entirely surprised that she will try anything to please and appease her mom — even resorting to lies in order to make herself seem like the Good Daughter she imagines would make Mama happy. After an epic career misfire in Las Vegas, however, Marty’s constructed self falls away in a hilarious and startling way. Marty, now forced to reevaluate and refocus, decides that the Old World might be a good place for a fresh start, so she accompanies Mama on a trip to the family home in southern Taiwan.

It all sounds very serious in the telling, but the writing is efficient and funny, with Marty’s voice making the whole thing really pop. Still, the centrality of the mother-daughter relationship and how Marty navigates its tremendous challenges charmed me more than I expected. Where another novel might make stronger use of a romance plot to keep us interested, Lai sidelines the romance a bit, giving the mother-daughter relationship enough room for serious exploration and nuance. This dynamic is where all that humor digs deep into the particular challenges of defining and asserting an artistic identity in the world — whether that world is the hectic atmosphere of New York City business, or the strong family landscape and rich tradition of small-town Taiwan, or even just within the heavy gravitational pull of a difficult parent. I don’t wish to spoil anything, so I will say only that there are no easy, one-size-fits-all answers for Marty, and it’s better that way. It’s a complicated journey to learn to help oneself, but it’s also a joy watching this fun and multidimensional character navigate it.

What blindsided me was the expert combination of humor and deep feeling that I found here. Where Not A Self Help Book initially engaged me with its light and enjoyable storytelling, I found that by the final pages I was impressed by the subtlety and the seriousness Lai treated the relationships between the women of the novel. Some, I think, will see parallels between this book and Bridget Jones’s Diary, as it shares some similarities with that book — epistolary storytelling, young female narrator, the preoccupation with self-help books. If, like me, you enjoyed Bridget Jones, you’ll probably delight in Marty Wu as well. My feeling, though, was that underneath the superficial similarities, Not A Self Help Book was an entirely different sort of novel. It’s one that cares deeply for its complicated female characters for their own sakes, and more than for their entertaining antics and romantic attachments. As I read, I felt keenly aware of real, lasting consequences for Marty Wu, as one who must become her own authority on bridging different cultures, ideals, geographies and life stages. A novel that can do all of this and still make me laugh out loud is one I can heartily recommend.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)