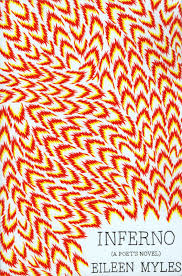

271 pgs/$16

OR Books, 2010

Imagine you come into a room all wooden and light, say it’s a bar, or an old converted church. You’ve come in out of the NYC street (LES or East or West Village) into this space; there’s Eileen Myles, sitting at the head of the great oak table. She’s reading from her book to a crowd you cannot see, but know are there. Only, she isn’t just reading; she’s pulling a thread, a thick gleaming wet copper strand of the parallel New York you have never seen and never will. She’s pulling this from out of her solar plexus, her navel, her heart, her –

You stare, you marvel. Who can do this? Pull this brilliant sparking length out of themselves, out of their body and into the world. Anyway, you are late, and sit down on the lowest seat at the table, not knowing what to do with your hands. Eileen doesn’t notice you, and why should she? She is speaking with the poets, from the vantage of The Poet. You feel a little humbled to be witness to this:

Ever since a time when poets were reciting not looking down at all, looking deeply into their own memories and reading or re-experiencing  and later when people did start writing the thing down it was a prose record, a literal recording, not wanting to make something happen on the page, instead just a way to hold it. The words still a pump from one poet’s inside. pumping blind.  And now these little containers, things that tell us, from so many centuries ago. Ancient broken pots. By the time I got my hands on one, when that occurred I just sort of wanted to cuff the white space of it. You know, knock it around. It exclaiming – to depict a world of so many surfaces, wider than a book, the world’s pouring would have to be a curve, the line would be running, cursive, infinity a fight. The words needed to splinter off in some way just to describe it, so that any one poem would be a surge and nothing more, an intrepid break in time.

There are many such moments of awe. Here is poetry as life, as fracture and space and texture and time – the many things poetry is apart from black marks on white page .  This is thrilling. This whole book is vivid and raw, broken now and then with a beautiful daring syntax. But as she reads – and it really does feel as if Myles is reading this, in one great breath, in your direction – you begin to fidget.

Sometimes, the poet is haughty. Sometimes cruel – as when she watches, lets, her dog maul a hedgehog on the lawn of a rich benefactor’s garden, and admits to enjoying the blood and the kill. Attitudes trouble you. The gossipy nature of things. He’s fat. She’s no good as a poet. I was with X, we did Y. Or maybe I did Y and X one before the other. (X and Y being married or otherwise). Â Yes, this is memoir, but this is also a novel, so why does it feel merely related, and not unpacked?

You do not ask for moral lessons. In a book that loosely purports to follow the structure of Dante’s Divine Comedy (not just the Inferno of the title, but the Purgatorio, and Heaven as well)Â you might expect more obvious structure. Advancement, if you could call it that. The voice of Myles is Virgil, and you are Dante, but Myles is telling you, oh, that’s Ulysses burning in fire forever. Or is telling stories so bright and compelling, but now you want to be guided down by her, with her, to the depths of hellishness and up again, curving through punishment or endurance, into bliss. Not with morality, and not with neat ends tied up. But –

Yes, Myles does tell her story of becoming a fulfilled poet and a lesbian (moving from straight to queer as though on a journey towards her aligned self), and she is so compelling to listen to – but the way she presents the story is also too much. Too much is said, retrod or half-trod the first time, stamped in the second. The fracturing, somewhat cyclical or refrain-driven nature of the writing which makes it so beautiful is also what detracts from a sense of cohesion. A sense, too, that the story is being told, but not particularly for you. All those names you don’t know, all those bright sparks, places, collectives, New York of the seventies, eighties, nineties. You don’t get to feel any of the heat. You are Dante as a blind ghost, hovering above Virgil’s head, as he tells and tells.

You get up from the table and make to leave. Eileen is holding court, and the copper keeps spooling brilliant out of her, like the ropes of lava that she encounters on Hawaii, and her story is thick and real, but not for you, no gift unless you know how to grasp these things, and you don’t, you are afraid to ask permission, unlike her, though maybe one day, you think, looking back on the scene through the window, breathing a little yourself against the glass, making it opaque so you can claim at least this little blankness for your own, you will.

Helen McClory was raised in both rural and urban Scotland. She has lived in Sydney and New York City and is currently to be found in the Old Town of Edinburgh in a three hundred year old flat opposite a tunnel into the underworld. The manuscript of her first novel KILEA won the Unbound Press Best Novel Award 2011, and publication is currently being sought for it. To keep the wire steady, Helen is working on a second novel about the intersections of love, failure and technology set in New York, New Mexico and Cornwall. Progress on this at: Schietree

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)