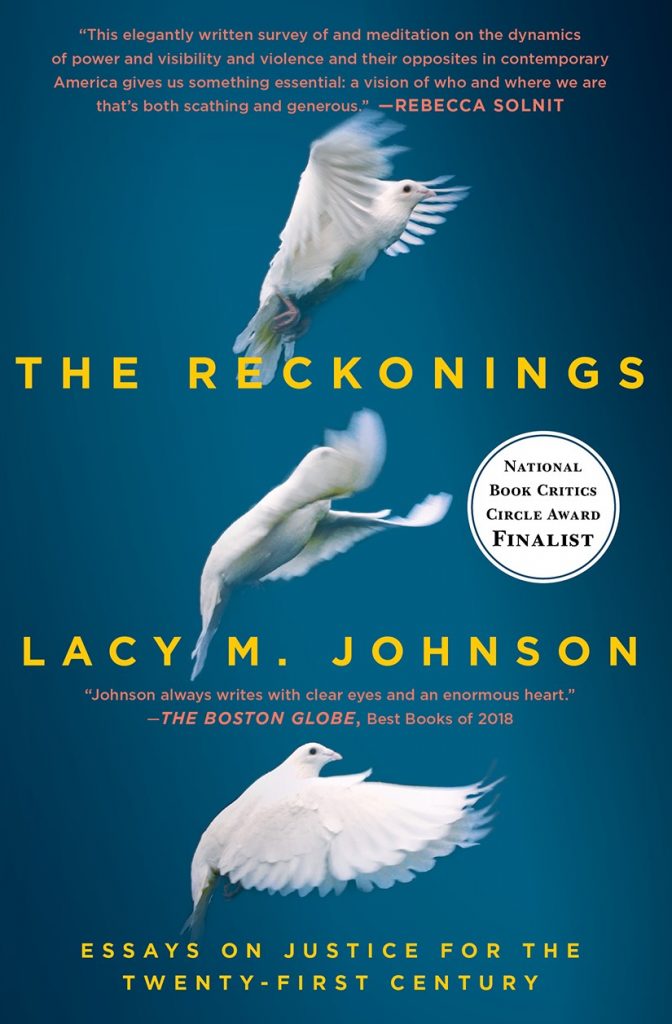

(Scribner, 2018)

INTERVIEW BY JO VARNISH

—

Lacy M. Johnson’s collection of essays, The Reckonings, is a powerful meditation on the issues of violence, justice and mercy. Through writing that is at times deeply personal, and her commentary on politics and culture, Johnson challenges the reader to examine their beliefs and their actions.

Jo Varnish: Your memoir, The Other Side, is a beautifully crafted account of an horrific trauma you experienced at the hands of a man who has evaded our societal norms of justice by fleeing the country. How did The Other Side inform or inspire your writing of The Reckonings?

Lacy M. Johnson: I feel like I’ve already told the story of how a question I was repeatedly asked while on tour for The Other Side prompted the inquiry I pursue in this book, so I’m going to answer a slightly different question, which is how these two books work together. In The Other Side I write the story of a horrifying trauma — how it changed me to survive being abused, kidnapped, raped, and very nearly murdered by a man I once loved. It changes me still. The Other Side is a story about memory and experience, about the fiction of before and after, and about how, because I will never “get over” what happened, I have instead learned to carry that story of it with me in ways that feel more or less okay.

The Reckonings is a different book — different in form because it’s a book of essays rather than a memoir, but also because it is a book in which I allow that earlier trauma to become a theoretical tool with which to interrogate violence more broadly — sexual violence, ecological and environmental violence, racial violence, gun violence. In the process of that interrogation, I realized that the many violences I write about in this book spring from the same source, which is the particularly white supremacist patriarchal belief that power only ever means power-over, and that strength is only ever synonymous with cruelty and force. What can trauma, as a theoretical lens, teach us about justice? How can occupying a vulnerable subject position — open, candid, exposed, unarmed — help us to interrogate the stories we tell about how stories should end, about what we owe to one another, and about how to build a world that is more just and equitable than the one we live in today? — these are the questions I wrestled with in The Reckonings, which is rooted in my own experience of violence, but uses that experience as a lens for looking at the world.

JV: Both The Reckonings and The Other Side were finalists for National Book Critics Circle Awards, and were widely critically acclaimed. The Reckonings has been described as a ‘thoughtful and probing collection,’ (Kirkus) and you as writing with ‘palpable compassion and brilliance,’ (LitHub). Does the validation of your words and sentiments resonating so strongly with your peers give you hope in this time of division and unease?

LCM: I don’t think of hope as the result of any kind of interaction — and certainly not of critics with my work — but rather as an “orientation of the spirit” (Vaclav Havel), or perhaps as an ethical commitment. When we look at the massive problems that face us in this moment — climate change, racial violence, sexual violence, mass shootings — the magnitude of each problem individually and collectively can feel like just too much to overcome from where we are right now. The scale is too massive, we tell ourselves, and we lose hope. But I think a lot about the trope in science fiction we have come to readily accept: that a person can travel to the past and make some small change that radically alters the future. But what we accept less readily is the idea that we can make small changes in the present that radically alter the future. I think hope is a commitment to action right now, an investment in a future that has not yet been revealed to us, and possibilities we can’t yet see.

JV: Lily Meyer, in her review of your book for NPR, wonders if the #metoo movement might be a reckoning. Do you view it as such?

LCM: Only partially. A true reckoning would require a more substantial shift in the balance of power. Perhaps you noticed how each time this movement makes a step forward, our stride is met with backlash, and a reframing of our collective narrative about the epidemic of sexual violence against women as an epidemic of false allegations about men. A real reckoning would make that reframing transparent and ineffective — or, better yet, impossible. I think we’re moving toward that but we still have a long way to go.

JV: Your essay On Mercy explores the meaning of mercy in relation to death row prisoners and terminally ill children. You write with grace and elegant restraint, and it is, I think, impossible not to be moved to tears as you take us with you to the children’s ward, and give us a glimpse at the lives of the children and their parents. Your threading of the inmates’ circumstances facing capital punishment and the terminally ill children feels natural and poignant in the context of mercy. What inspired you to juxtapose what initially seem to be such disparate situations?

LCM: “On Mercy” is actually the first essay I wrote for this collection. I had been traveling in support of The Other Side and kept getting asked this question about whether I wanted my rapist to be murdered, and a friend who works in criminal justice very helpfully suggested Autobiography of an Execution by David Dow — a lawyer in Texas who founded the Texas Innocence Network to defend people on death row — and that book led me to Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson, who is the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative in Alabama. Both books engage the question I had begun rolling around in my head — how are we to say what anyone deserves? — but approach that question in order to make a critique of the death penalty. I had just recently completed a year of teaching writing in a pediatric cancer ward, and noticed that in the discourse around the death penalty, there is a lot of talk about mercy, about alleviating suffering, about dignity, and in some ways that mirrors the discourse around end of life care that I had overheard during my year teaching in the hospital, though what people meant by those terms when talking about dying children was very different from what they meant when talking about men who are scheduled to be murdered by the state. During a single year, several of my students died and thirteen men were executed by the state of Texas, and the circumstances of their deaths were the subject of two very different but overlapping conversations about mercy: in one case that word meant ending suffering for the innocent and in the other it meant ending life for the guilty. I wanted to think through how one word could have such radically divergent meanings.

(Lacy M. Johnson, courtesy of the author)

JV: In Goliath, you write, ‘We human beings are not born with prejudices. Always they are made for us by someone who wants something. We are told we have enemies who hate us, who want to make war with us […]’ Do you think that it is easier to elicit fear in human beings than compassion? Are there societal factors that predispose an individual to a reaction of fear instead of empathy?

LCM: No, I don’t think we’re predisposed to fear and suspicion and hatred. I’m writing in that essay about anti-Muslim racism following 9/11, and something that didn’t make it into that essay was that following the attack on the World Trade Center I spent a year working as an Americorps VISTA volunteer and my particular placement was to work as a Peace Educator. As part of the training for that position, I learned that by the age of 10 most children have witnessed 100,000 acts of violence in the media, and that because they are naturally compassionate and empathetic, bearing witness to such repeated and prolonged violence damages their empathy in profound and devastating ways. It is far easier to teach a person to fear another if they have already learned not to feel for them.

JV: You describe admitting for the first time in public that you were kidnapped and assaulted in your essay, Speak Truth to Power. You go on to detail a disgusting comment made by a professor in Georgia, jealous of your success, implying that you may have invented the story. I know, as I am sure most do, women who have been raped who have not reported the violence against them. Can you feel the tide shifting against the established patriarchal mindset towards one more inclined to embrace those who have been violated through harassment or assault?

LCM: Yes, It does feel like things are shifting away from a patriarchal mindset, and I think that is part of a broader move away from white supremacist patriarchal ideology. It also feels like the hold the petroligarchy has on our natural resources is slipping, that capitalism is about to collapse under the pressure of extreme economic inequality, and that part of the pressure on these institutions to fail is a growing collective awareness that these are not separate institutions but a single desire to bring the many under the control of the few, and that this desire goes by many different names. This isn’t happening on its own of course, but is the result of generations of social, political, emotional, and psychic labor, and usually the labor of people of color. I think it’s important to note that if it feels like we’re making any progress at all, we have our elders to thank for it.

JV: In your closing essay, Make Way for Joy, you write, ‘Justice means we repair instead of repeat.’ This line struck me as call to action for conscious effort, in ourselves, and in the wider community. Do you think today’s younger generation is more inclined, through their use of social media and their instant connection to an audience, for example, to fight for change, or do you think they are less inclined, perhaps in part due to the constant scrutiny that comes along with that use of social media?

LCM: I don’t think this is a generational issue so much as a cultural one. I notice that many of my students, for example, are reluctant to engage in activism, but if we look to the Parkland students we can see the ways that this generation is not only capable of very effective activism, but are committed to it because the generations before them have dropped the ball. (Fellow Gen Xers, I’m looking at you.) People often deride Millennials for our own cultural failures, but let’s remember that Occupy Wallstreet was largely fueled by the energy of Millennials, many of whom had been economically disenfranchised by the stock market crash and were protesting that there was no accountability for the corporate greed that got us into that mess in the first place, though there were bailouts to rescue those corporations from the consequences of their own actions. My advice to my students in Generation Z, who might feel that the pressure of various scrutinies inhibits their freedom to “step out of line” and into what Representative John Lewis might call the “good trouble” of civil disobedience, is that there is no one who will ever give you permission to practice your own freedoms except yourself, which is why we must support our collective liberation in all the ways we know how.

—

Lacy M. Johnson is a Houston-based professor, curator, activist, and author of the essay collection The Reckonings, the memoir The Other Side — both National Book Critics Circle Award finalists — and the memoir Trespasses. Her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Virginia Quarterly Review, Tin House, Guernica, and elsewhere. She teaches creative nonfiction at Rice University and is the Founding Director of the Houston Flood Museum.

Having moved from England aged 24, Jo Varnish now lives in Maplewood, New Jersey. Her short stories, creative nonfiction, and poetry have recently appeared, or are forthcoming, in X-R-A-Y Literary Magazine, Manqué Magazine, Brevity Blog and Nine Muses Poetry. Last year, Jo was a writer in residence at L’Atelier Writers in France. Currently studying for her MFA, Jo can be found on twitter as @jovarnish1.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)