BY BRIAN ALESSANDRO

—

AT FIRST, SHE HESITATED TO CLICK ON THE LINK. As a rule, Lorna deleted emails from unknown senders, though few ever made it past her spam filter. She felt safe opening this one. The subject line read “Dr. Truman-Hall, I am NOT a Robot! Please read me! EOM.”

Lorna clicked the embedded URL, a YouTube destination, and watched herself give a lecture from two days ago. She recalled that it was the day she’d slipped up and gone on a rant in her Gendering Culture class. She had discussed the myth of rape, about how there were parts of the violation that could be construed as desirable (“I mean, who doesn’t like a show of strength?” she’d said), the complicity of females in their own degradation, the “problem” with gay and effeminate men, and the sovereignty of heterosexual masculinity. She had held these views for years and written about them in numerous articles and books, but pushback had historically been confined to civil discourse between academics, lively and respectful debates in university auditoriums. Her new book, The Wanton Feminine, forthcoming in a few months from Dowling House, her most high-profile publisher, would set the record straight.

The clip had only been posted a day ago, but already yielded four hundred and twenty thousand views and eighty-seven thousand comments, almost all of which excoriated Lorna. Some even demanded a live-streamed suicide.

“Though I consider myself a progressive, my gripe with the left is that they absent things like common sense, basic biology, and ancient history.” Lorna watched herself address the students in the five-minute clip. “Girls need to smarten up and start acknowledging human nature—and especially male nature—as something concrete, not theoretical or elastic. Not something that will bend to the whims of political correctness. The brain has a tendency to mistake pursuit for desire, but that’s not entirely what I’m talking about here. I do believe that we’re built this way on an evolutionary level to perpetuate the species, though. It follows that those alpha men who effectuate change and keep the world spinning forward are also inclined to conquer sexually. Without beta permission, without omega timidity. They are biologically pushed to spread their seed. To propagate. Shaming those men into believing that there’s something wrong with that impulse will surely extinguish their flames. The constructive fires that build cities and cure diseases and produce great art. Women are neurologically wired to accept the conquest because they know on some unconscious level that they’re welcoming in an alpha seed and thereby helping civilization advance. And for the last time, please stop writing about the fluidity of gender in your papers. Gender is not fluid. It’s as fixed as a tumor or a clogged artery.”

NOW Lorna looked around her austere office and wondered if she’d been playing the clip too loud, if anyone in the hall could have heard it. She lowered the volume and put on closed captioning for the duration of the video as she searched her memory for which students might have had his or her phone out during class. As there were over eighty students in attendance, the clandestine recorder was as much a mystery as the anonymous sender of the email.

LORNA WEATHERED THE STARES AND SNEERS with admirable indifference as she walked across campus. The muffled comments and audible hisses were more impactful—how she loathed this neologism or more precisely the back-formation of the word into an adjective— blows to withstand. CUNY Merkin’s faculty and students were nothing if not up on their viral video sensations. And all the chatter that would follow. Multiple Twitter storms and FaceBook fusillades erupted. She had happened upon them after closing the YouTube video and researching the national witch hunt playing out online. It all left her dazzled. She almost chimed in but decided she’d better not.

Even the barista at her favorite café across the street was awkward when handing her the receipt. She’d been an affable young woman, a graduate student who was fond of Lorna’s work and conversation, if not tips. Her nametag read “Sam,” but Lorna always thought she looked more like a Sue. The young woman flashed a half-smile and busily moved on to the next customer waiting in line, eyeballing Lorna with unease, if not impoliteness. Were so many people really that plugged into YouTube? It’s not as if the clip had been broadcast on any of the major networks or 24-hour news channels. Not yet, anyway.

A group of protestors, politically-active doctoral candidates that Lorna had recognized from past colloquia, had gathered at Merkin’s main entrance and held placards that read “No Room for Hate Speech!” and “Beware Traitors Infiltrating from Within!” and “Stop the Sexists!” and “#MeToo is NOT a Passing Fad!” and “Toxic Masculinity is a Cloak That Even Women Can Don!” They shouted their slogans with theatrical brio.

Lorna sipped her hot black coffee and hadn’t realized that the demonstrations had been organized in her honor, even though they’d co-opted one of her phrases—donning the masculine cloak. It became clear that she was the butt of the joke—that’s what this whole farce was, after all, a joke— when one of the protestors saw her and began hissing. The others followed suit. Lorna turned away, red face and wide-eyed, and brushed past them, spilling some of her coffee on her pants and scuffing the side of her shoe on the base of a nearby concrete planter.

CONSTANCE DE LA ROSA, the chair of the cultural studies department, entered Lorna’s office with authority. Closing in on sixty-five, Constance was breathless, if not flush, by having made the urgent visit. As if she had run up the stairs from her office three floors below.

Lorna, obfuscating any signs of annoyance, looked at her. “Constance?”

“Are you kidding me with all this?” Constance spoke in a smooth, unnecessarily breathy purr. The kind of feminine, neither sexy nor expedient, that always got on Lorna’s nerves.

“What?” said Lorna, slouching.

Constance, her silver-black hair coming slowly undone from its bun, paced with a menacing majesty. “That video, Lorna—let’s get right to it, you know the one I mean—the one that’s been all over social media all morning. It’s going to cause some trouble. It is causing trouble!”

Lorna stood, began watering her numerous succulents, and nodded, absorbing Constance’s admonishment. “I didn’t’ know I was being recorded, Constance.”

“That’s beside the point. The things you were saying shouldn’t have been said in the first place! The department doesn’t need that kind of attention. Not in this climate.”

“The department doesn’t? Or the university doesn’t?”

Constance’s cheeks bunched when she winced. “What difference does it make? The department is the university!”

Lorna continued moving around her office with the pitcher. The plants were thirsty. “Oh, an honest and direct answer. I like that!”

Constance hurried after her. “We don’t support your views, Lorna. Not on this one.”

Lorna stopped again. “What’s the problem, exactly, Constance? What’s so threatening about—”

“You can’t be serious asking me that? What you’ve said about women and rape and gay people … it’s just downright bullying, Lorna. And frankly bigotry.”

Lorna’s top lip curled into a livid smirk. “The hypocrisy is stomach-turning.”

“There’s no hypocrisy!”

“Constance …”

“And we won’t even get into how you believe women secretly desire being oppressed within patriarchal systems. From that ludicrous article you had published last month! The Atlantic used to have standards—”

“I never said they desire being oppressed. I said they long to be named, designated: ‘Whore.’ ‘Mother.’ ‘Loose.’ ‘Frigid.’ Women are like all other people. They require leadership.”

“And that appalling thing you wrote about a woman’s worth measured by how much they’re willing to –”

“Look, these kids spend upwards of seventy-five thousand dollars a year on a liberal education, to think freely, to expand their scope, and yet you’re prepared to deny their educators the right to think liberally, to speak freely! It’s the exact definition of hypocrisy, Dr. De La Rosa!”

Constance gathered herself, took in a deep, hearty breath worthy of a master vinyasa yogi, and spoke softly, slowly with eyelids firmly half-mast. “And Slate Review just published an essay denouncing you. They criticized Merkin for keeping you on staff. They say we’re complicit. Aiding and abetting a criminal.”

Lorna scoffed.

“And it’s had almost two hundred thousand hits already, Lorna. It was just released this afternoon.”

Lorna sobered up. Retrieved her stoic mask. “Clearly, my words have been taken out of context and distorted. The Wanton Feminine will be out in a few months. I’ll be touring with the book and I’ll be able to clear up all the confusion.”

Constance shook her head, her eyes heavier than before. “We’re working on having the video taken down, but as far as the article … it doesn’t help and now in light of what you said in class … We can’t have it. Write a retraction.”

“I won’t do that.”

“Then you’re alone. The department and the president will send editorials of their own to The Times distancing ourselves from your views. And from you, Lorna.”

Lorna pondered the threat with a demonstrative gusto. She shrugged. “I’m tenured. And need to grade papers.”

Constance left. Lorna watched the YouTube video three more times, counting the increasing number of hits with each viewing.

LORNA’S EIGHTY-FOUR PUPILS LISTENED with a rapt attentiveness. Their tacit enthusiasm would electrify Merkin’s largest lecture hall. Or so she had relished believing. She got off on the energy that her seminars had elicited in undergraduates, apparently. Prided herself on telling the kind of truth missing from contemporary academia: that of the ugly, offensive variety. She owned her ugliness. Cuddled her offensiveness. Cultural studies as a subject was still relatively new and students were eager to learn as much critical theory as possible if for no other reason than to show off their creative connections between disciplines and earth-shattering insights at cocktail parties.

She should have made an attempt to move on and away from the YouTube clip, but the cold war brewing between her pupils, ghoulishly bathed in the blue-white glow of laptop screens, and herself was a battle from which she’d not shrink. Though the circumstances couldn’t be more awkward, Lorna would make the video the centerpiece of today’s Gendering Culture class. And it being a lecture, there’d be fewer opportunities for talkback or scrutiny.

“Good afternoon. You have by now all seen this YouTube clip of my lecture last week, which has been circulating on social media, I’m sure? You were all at that session.” Lorna paused with a delightful smile and gay eyes. “And one of you even recorded it.”

Some students shifted in their seats, others leered, ready for an apology or a confession or a gloriously well-executed excuse

“What I said wasn’t new. I’ve been writing about it for the past twenty years. You’ve all had time to read my book, The Civilized Masculine: Unnecessary Crisis in The Age of Traumatized Selfhood and should know my positions by now. None of this was done for shock value. Or to hurt anymore.”

A male student, black, preppy, bespectacled, and likely a senior based on his age, raised his hand but began speaking before Lorna had a chance to call on him. “You really think that women ask for rape?”

Lorna sighed and hunched a bit, approximated well the mien of an embattled woman. “I see my comments were taken out of context. Tragically, you all weren’t able to detect the nuance and subtext of my delivery. If only you had been keeping up with the reading, you’d have been able to better understand what I meant.”

Lorna caught them, the faces, the expressions made by newly educated kids who liked to prove street credibility by schooling others, usually older and in modes of power, like parents or employers or teachers. They rolled eyes and shrugged shoulders and curled lips into mocking smirks.

Actually, she could never be sure if their sneers were for her or her intended targets.

“So, then, a summary.” Lorna reviewed her book, thumbed through the dog-eared pages, then put it down. “Listen, I’m less interested in dwelling on the role of women in all of this. The so-called victims or ‘receptacles.’ They’ll get their hearing in my new book, The Wanton Feminine, coming in a few months. No, no. We’d be better served understanding the so-called perpetrators, the ‘violators.’ Men. When scrutinizing the behavior patterns and reactions exhibited by males in today’s society one is wise to consider the archetypal roots found in male icons of centuries and millennia past. Ramses II. Alexander the Great. Caesar Augustus. Henry VIII. Napoleon. King Herod. King Solomon. Hitler. Though their pride ultimately led them to ruin, it also fueled a quest for greatness, and here we are after all this time still discussing their indubitable glories.”

Some of the students, those who weren’t busy muttering foul sentiments under their breath, nodded and jotted notes or punched keys. They annotated copies of her article. They wrote immediate responses, rebuttals. They logged their triggers.

“Envy between even heterosexual males spawns a strange desire. The second-fiddle beta or lowest-rung omega endeavors not to just steal the alpha’s place, but to supplant the alpha himself! To be him. Or defeat him. This odd craving generates a disruption in the beta’s or omega’s ego. The disrupted ego occasions bizarre role plays, toxic theater, and dangerous charades. The said role plays, theater, and charades foster varying humiliations. Their humiliations cause carnage. The tools of their combat and disaster are now voyeuristic, judgmental bystanders, ever-recording cellphone cameras, and an omniscient internet. Before, it was a coliseum. The envy cuts deep. A need to assert and prove one’s self arises. Women, caught in between, become collateral damage. Remarkable this masculine toxicity.”

Some of the young students sniggered but admitted uneasy truths, anyway. Others shifted again with a detectable agitation. The note-taking and keyboard clacking persisted. Lorna paused for a dramatic beat, seductively, sweetly eyeballing the front row, all of whom looked up at her with a dense air of uneasiness. She diffused with a gentle disposition. Maternal, soothing.

“Men, not broadly mankind, but straight men specifically, are prone to self-immolation. They are ruled by the command to conquer and create. When they find themselves unable to do either they choose destruction and death over surrender and submission. And there always remains one obstacle too insurmountable to fathom for the great heroes of history, be it India for the Macedonian emperor or Waterloo for the French dwarf. All supreme men are hungry dogs seeking domination. And, yes, I realize that Alexander was bi.”

Lorna felt the ions shift in the lecture hall, the eagerness to share thoughts and push back against theories that didn’t sit well was in the dense, uneasy air. And yet she was capable of making the suspense linger. She would push the lesson and her students’ nerves further. The tension was necessary as it provoked concentration and remembrance; she was a professor who demanded absolute concentration and complete remembrance.

These lectures were her art and she would somehow reclaim that goddamn, motherfucking YouTube video.

“It takes literal balls to build a culture. The bold push from the testes produces civilization and advancement. My blend of feminism permits the worship of men who have made the world their own and those few women who have … donned the masculine cloak … and done so for themselves: Cleopatra, Elizabeth I and even her ruthless half-sister Mary, Victoria, Thatcher, Clinton. Essentialism has its limits as a philosophy. As a science, it is an experiment intended for ceaseless empirical research.”

Whereas it had been the more delicate men who were most vocal in their braying at her pronouncements up until this point, the women in the room had now suddenly found themselves jeering their teacher’s pseudo-defense. Lorna enjoyed this the most. To trouble young girls, to upend their new, ill-informed feminism, to chip away at the patina of their self-congratulatory activism and performative outrage. But still, she worked toward disarming with a loving glow.

Several female students were now shaking their heads and had crossed their arms, silently and in solidarity refusing to take notes, protesting any more propaganda from this self-loathing woman. Lorna’s calculations were not off; by her estimates two-thirds of the whole class will have joined them by the time her session was up.

“Several volumes of this epic could be filled with the data amassed on the transformations undergone by the alpha and his beta. And their omega. Their change is seemingly ineluctable. It must be a demoralizing revelation indeed when these men find out that they are unable to control their own personalities, and that they had seized control of them like angry poltergeists, intent on either breaking them or recreating them.”

Lorna could tell at this point that several of her scrawnier, meek pupils were searching the auditorium for the jocks, the models, the physically superior specimens. The inadequacies screamed. The jocks, the models themselves basked in the silent adulation. The bitter atoms between the alphas and betas and omegas caused the female students to tingle in all the appropriate places. Lorna tingled, too.

“Finding comparisons between the ‘tournaments’ held by the competing men and idolatry and the ancient gods requires no leap of faith. Even as the beta and omega succumb wholeheartedly to nihilism and even anarchy in their self-loathing-fueled destruction. He who shirked the dictates of logic and abided by the commands of delusion. Fastidiously, and with fetishistic relish, the beta and the omega work toward the solution to his problem: debilitating self-doubt in the shadow of their alpha.”

The small, quiet, bookish boys—the first to have been audible in their disagreement— had begun to rock back and forth in their seats, their knuckles white, their cheeks flush. Lorna imagined that the jocks, the models were by now fluffing their feathers, their tumescence likely apparent had she looked closer. She couldn’t be sure who’d recorded her, but she could manage the temperature in the room. And when tactical, quiet her judges with congeniality.

“The lazy analysis suggests that men are inherently sadistic and women masochistic. This is one of life’s great fallacies. Men, not women, are the true masochists as their failure is inevitable and the suffering their conceit is destined to afford them will reveal itself as the humiliation for which they implicitly thirst. For more on this see my previous examination of self-importance, Theater of Violent Happiness published in 2010 by Lakehouse Ltd.”

The females in the classroom scribbled with personal grudges. Lorna wondered what criticisms they were inventorying, what caricatures of her they were drawing, what phallic symbols they were sketching. She made eye contact with one student, an East Asian girl whose expression ambiguously bordered on scorn, or maybe rapt attentiveness. Lorna averted her eyes, set them on her notes.

“Please understand this. The beta and the omega do not pine for success or power in the conventional Western sense. He seeks no fame or grandeur for their own sake. Rather, he is after a deeper-dwelling fish. He plumbs depths, leagues-beneath the surface. He fights murderously for self-acceptance. His introspection is so focused and pointed that one would feel a sense of shame when in proximity, first for themselves for not digging as ardently, and then for him, for the beta and the omega, for doing so. A man of his time and at a certain age ought to turn his attention to others, elsewhere, outward. He should come to the cold realization that he and his contentment or sense of achievement or worth no longer matter. The alpha is so satisfied with who he has manifested into that self-reflection is to him a vain, pointless exercise.”

Lorna thought about her husband Risk and son Theo, and their designations. How would she rank them? Among the alphas? Certainly not. Though Risk would like to think of himself as worthy of the station. He was no omega. Beta, then. And what about Theo? Her son was firmly planted amid the omegas. The lowest. Her theories had originated as a reaction to her marriage. They were developed as a reaction to her son. Risk engendered an intolerance with faux, forced manliness, while Theo implanted an impatience with a complete disavowal of natural states.

A young female student—Hispanic, short, overweight, and starter stylish in pink and black plaid—raised her hand with a fiery ardor, waving a paperback novel in the air; she sighed irritably. “But wait!”

Lorna’s eyes rounded. She paused, clasped her hands, and stood with a cocked head and warm smile like an unthreatening grandma. “Yes, my dear?”

“What about what Herman Hesse wrote in Narcissus and Goldmund? We’re reading it now in our German literature class,” said the girl, thumbing through the book to a dog-eared page. “Here. ‘We are sun and moon, dear friend; we are sea and land. It is not our purpose to become each other; it is to recognize each other, to learn to see the other and honor him for what he is: each the other’s opposite and complement.’ Why does there have to always be a pissing contest?”

“Well, Hesse meant well as a permissive fiction writer, but that’s really all it is. Fiction. Also, his blend of pseudo-spirituality is to blame for this awful wave of nonsensical New Age pop psychology. He was a fraud and a weakling, I’m afraid. A narcissistic coward.”

The ardent student looked down and closed her copy of Hesse’s novel. This business of analyzing student psychology in the moment of intellectual delivery was a tricky affair. It had never thrown Lorna before, but these days, what with the video burning down her reputation, the steel had run from her nerves, and she was becoming distracted and driven off course. She redirected her eyes once again and fixed on a crack in the wall, found comfort in its inevitability.

Lesser critical theorists—typical critical theorists—relied solely on the narrow and limited tradition of the cultural Marxists. It’s all magical thinking, not honest, comprehensive life. Lorna couldn’t stomach the hypocrisy.

A thin-boned boy swaddled in oversized sweaters and pants, clashing patterns, and uncombed hair, twitchy and bothered, raised his hand and began to sweat. Lorna nodded in his direction.

When the thin boy spoke, it was with shallow breaths: “But, I think these are false equivalencies: gay men, beta and omega. Straight men, alpha. Feminine behavior: beta and omega. Masculinity: alpha. I just … I think they’re … false!”

Lorna landed her grandmotherly posturing with a kindly smile. “Oh, but I don’t think so, young man. I just believe that gay men, effeminate men ought to resign themselves to their beta and omega statuses. They have their place in the culture, but it’s just not behind the wheel of the big ship, is all. And straight men must embrace and even protect their masculinity because it is the primary engine that drives civilization. It’s nothing to feel ashamed about. Don’t buy into this ridiculous new narrative that they’re selling you! Look, the Left produces victimhood, plain and simple! They require an oppressor and an oppressed in order for their industry to thrive. You, my sweet child, are not a victim.”

The boy had reminded Lorna of her son. It’s why she wasn’t moved by his trembles, pouting, and deep breathing.

Risk had been his most self-absorbed. Most childish in his pursuits. Playing at boyhood aspirations. And Theo was getting smaller by the day, shrinking into himself, into a cowed and embarrassing boy. They had failed her. She had failed them. Everyone broke contract.

“Family is a sort of a business, a corporation, in which matters of facilities and operations must be attended to. It is a concept that a leader must internalize to keep the institution running through supervision and execution of daily functions, accountability, and principles of growth and improvement. If the omega or beta is the manager of his company, the head of his household, he is remiss in his responsibilities and derelict of duty. And the employees, that is, the wife and child, duly suffer. A culture of criminal neglect and routine embarrassment is one that will not persist.”

Students grumbled to one another, the hall reverberating impatient hisses, as the session was almost over, and lunch was to be had. Lorna needed a strong finisher. She always ended her classes with a punch, something for the kiddies to mull over until the next session. Three hands were raised. She ignored them. Two students had already left early, probably to use the bathroom or smoke a cigarette. No matter, she had plenty of others to populate her captive audience.

“What barbaric grief—the episodes unfurled by the child, the child of the beta or omega, his own depraved public outreach, echoing that of his father. The inherited tendencies toward exhibitionism and self-defeat rear ugly heads. On parity with the tragic Greeks or saddest Shakespeare. And the wife—her own petty, spiteful journey away from kin and into sin. Astonishing, truly, how the dissolution of a perfectly normal and well-adjusted family is begotten by such infinitesimal insults and small, needy flashes of unwise pride. Consider Emerson and Thoreau. The transcendental way. Consider their grave admonishments. Not to stray too far from nature, God, the humble soul. Modest needs. They warned of disingenuousness, of flinging yourself too far from earth. The disconnected face unhappy ends. They fail at grace. Nature scolds them for their hubris. It’s a note worth taking.”

The students at this point had become lost in the maze Dr. Hall-Truman had built around them. Finding themselves in the middle of the labyrinth, the students turned and stared blankly at one another, waiting for a roadmap out, but Lorna had already packed up for the day. The lecture had ended, and she would leave no compass.

ODDLY, LORNA’S HUSBAND RISK TRUMAN had also melted down on a public stage. In a series of performances purposefully recorded for the whole world to consume. Because he was affluent, he could afford the endeavors. An investment banker at a leading hedge fund, Risk spent his way through it, first by funding a charter school network in the South Bronx and Harlem, then by hiring himself as a history teacher (to live out the fantasy of a common man and role model of wayward, impressionable, minority youth) and now he had begun to orchestrate team-building exercises that served as a cover for competitions between himself and the school’s younger, fitter, more attractive science teacher, Dominick Bonaventura. Risk shared his own YouTube channel with Lorna, so far consisting of only several videos, but each boasting thousands of views. She’d already told him about her own Internet stardom, but he dismissed it as a passing fad.

“The way these things work, darling, it’ll blow over before you know it, and it’s not like my channel where I made something, you know? This is just some punk student who’s too delicate a snowflake to handle the education you’re trying to give them. Plus, make this work for you! It’s. great PR! You have a new book coming out soon, right? You can’t pay for this kind of exposure! Use the hype!

Risk competed and strategized so impulsively it had become as natural as breathing.

“Who shot all of these?” asked Lorna, watching her husband first indoor rock climb in Washington Heights, then run an outdoor obstacle course in Upstate New York, then engage in a Muay Thai kickboxing session in Bushwick. In each video, Risk was both predatory and bested. His prey and eventual victor, the young Mr. Bonaventura, Risk’s junior by twenty years.

Risk positioned the laptop on a coffee table in the middle of the living room of their too-large Upper West Side apartment. “Darnell, he’s great with the camera, isn’t he?”

Had he not realized how petty and pathetic he was coming across in these clips? “I don’t understand, Risk? What are these for?”

“Just for fun, Lorna. God. Not everything has to be some symbol for something else.”

Lorna imagined these clips conflagrating, her husband becoming the poster boy for middle-aged men trying too hard to prove their manliness and failing. The insecurity was the stuff of legend, and Lorna would be sure to file it away for another essay. She sometimes wondered how closely her husband paid attention to her work if he knew she’d been all the while writing about him and men like him. Resenting that level of clumsy, ineffectual machismo.

He said, chillingly to Lorna: “Have you given any more thought to Spain?”

Risk’s next escapade, after acting the part of a teacher and businessman, was to pay his way into the bullfighting circles of Madrid and become a matador. It was an outrageous aspiration, but one he would pursue, anyway. He’d already contacted the most famous bullfighter in the country, Javier Alegria, who maintained a cordial relationship with him through Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Perhaps now that he was being routinely defeated by his charismatic young colleague/ employee, and inexplicably—masochistically—sharing it with the consumptive world, Risk was ready to move on. If things got worse in her own virtual life, Lorna would have to move on, too.

Their son, Theo, “Thee Thee” to friends and in online video games, was a different animal, entirely. She knew he’d caught wind of her writings about feminine, queer men. Her son, being both feminine and queer, had stopped talking to her for months at a time whenever she’d publish a book or article or give a lecture on the subject. He’d felt like her lab rat, the thing she didn’t want but needed for the professional profile. Wife, mother, scholar. As a straight woman, it softened her. Made her accessible. All jobs now required a relatable narrative and a likable protagonist. Lorna could be likable. At least on paper.

“Since you’re YouTube famous now, mom, I guess it’s high time I share my channel with you!”

Had everyone in her family been a social media superstar?

Theo’s soft manner and voice, his pasty complexion, his lanky frame. All of it rankled Lorna, but she’d tried to be pleasant. Conceal her distaste for his manifestation. A child knows, though. Theo possessed an uncanny knack for picking up on his mother’s suppressed loathing

His video collection consisted of strangers taking nasty spills, dropping boxes, fumbling groceries, crashing bicycles, tumbling down staircases.

“What is this? Are they friends of yours? I don’t get it, Theo.”

“They’re just people, like, making asses of themselves. It’s all about public humiliation.”

“Well, why?”

She was asking him, her son, with his not completely masculine nickname. Thee thee

Theo looked at his mother as though she were simple. “Because … it’s funny.”

“Is it, though?”

Lorna looked at her son’s laptop and watched one of the videos. A twentysomething white yuppie in an expensive suit getting socked in the mouth while smoking a Cuban cigar in front of Trump Tower on 5th Avenue. The attacker was a homeless man, probably sixty or sixty-five-years old, and shorter than the victim. The assailant had to leap to connect with the gangly investment banker’s lofty jaw, knocking the cigar across the street and the target on his ass.

Lorna had wondered if Theo had paid these people to make fools of themselves or if he’d secretly orchestrated the accidents. An oil slick. A nail. A screw. Hidden twine. A drummed-up altercation. To what extent of sabotage was her son capable?

“Well, all these people seem to think so.” Theo pointed to the views and likes and comments. The numbers still fell short of her own. This was a competition that she had no interest in winning. “I mean, we can’t all be like you, Mom. Instant, overnight celebrity!”

Theo trundled back into his bedroom, a place of comic books, drawing pads, homoerotic cartoon characters sodomizing each other, nests of wires and gadgets and old cell phones and laptops, walls of rapidly outdated video game systems, classic comic books, superhero and horror Funko Pop figurines, caringly-framed posters of the drag queens Adore Delano, Sharon Needles, and Bianca Del Rio, vintage board games, and all the stuffed toys he’d held onto from his childhood. He was the spawn of a nationally vilified cultural studies professor and stunted investment banker living out boyhood fantasies, after all. Lorna should appreciate that much, he always thought; he might be a sissy but at least he was interesting.

AMID the Twitter storm and FaceBook fusillade that she’d periodically check in on, without commenting, and against her better judgement, Lorna, in bed on her iPhone, found two posts sticking to her, one from a college student in Chicago, a male, who wrote about her sermon: “The weak violently protect the powerful. For the poor, the rich, or in Dr. Hall-Truman’s case, for women—men, because there’s an aspiration to become such.” Another, a female high school student in Tucson, called her out in a post: “Social media raised me, not my parents. And it’s because of adults like you, I’m grateful for that!!!”

THE WALL CLOSEST TO LORNA’S DESK was plastered with images of men. Prime men. Primal men. Merciless leaders. Libidinal warriors. Even Russell Crowe in Gladiator and the strapping Spartans with the airbrushed abs in 300. The subjects weren’t erotic in nature however the emphasis was on physique and physicality. In fact, her entire outsized office was full of paintings, drawings, and photographs of powerful bodies in glorious, gorgeous postures. She reviewed a stack of synthesized alpha biographies. Her connections between ancient rulers and contemporary athletes prompted many in academia to compare her to Camille Paglia, someone she had known for a short while when she taught for a year at the University of Pennsylvania as a visiting professor soon after earning her doctorate.

Lorna’s notes on Sargon of the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia, Ghengis Khan, and Ramses II were as voluminous as her dossiers on Michael Jordan, Cristiano Ronaldo, and Roger Federer. Lorna was working toward building bridges between the men of their respective eras and the adoration and emulation they elicited in their followers. She considered modern male megastars to be on a parity with the supreme commanders of history.

Her peers in the department had once supported her views, knowing that it would help her forge a distinction in the field; cultural studies was messy and turbulent and those few whose hypotheses could deliver the zeitgeist in palpable sound bites tended to reap a good deal of attention, appearing on Real Time with Bill Maher. Judith Butler and Jordan Peterson had been recent “co-stars”.

It had been a week since the video leaked on YouTube. The faculty had since rescinded their initial encouragement.

“This bit goes too far, I think, dear.”

Geraldine was a mainstay at Merkin who was closing in on seventy and had earned her Ph.D. in the 1970s, a time when such grand accomplishments felt rarified and radical, especially for women. Her mentor was the eminent and still clandestine Julia Kristeva. Dr. Herzer’s writings on “the abject” mystified her graduate students and sickened her critics who thought that she was too fixated on notions of good and bad breasts, authoritarian and inconsistent parenting and the instability it engenders in the needy, avoidant children they raise.

Lorna stopped watering her succulents and turned to Geraldine. “Which?”

“Here,” said Geraldine, poking the text with the tip of her red pen. “You state all-too-assuredly that even the most accomplished women ought to revere men as the chief builders and managers. That all women need to support their constructions and influence.”

Lorna’s eyes sharpened. “How’s it too far, Geraldine?”

“Oh, Lorna, come on now, I know you value your provocations and polemics, but this is a bit much, no? Especially after the YouTube business. You know, our students complain to me. To us.”

Lorna continued watering the succulents. One, robust and virile in purple, took the water aggressively. She thought she heard it suck in the moisture. Everything thirsted.

“I mean, it’s one thing to criticize men for their compulsion to fight and quibble over penis size, but it’s quite another to suggest that women should worship at the altar of their narcissistic bravado.”

“Okay, Geraldine. I get it. This has nothing to do with the article. Nothing about my work has changed. This is about the video.”

Geraldine’s eyes narrowed. “The video, yes, and the murmur across campus of students who feel unsafe here because of what you’ve said. You’ve no idea the number who want to file a class-action lawsuit.”

Though her office was always the coldest in the wing, Lorna managed to chill Geraldine with her gaze more thoroughly than did the temperature. The artic atmosphere warmed considerably when the remainder of the cultural studies staff walked in ready for their monthly department meeting.

The men entered laughing. Thomas Chen was a short, sinewy Beijing exponent. Matthew Bowman, a ginger from Rhode Island whose years of sprinting left him with disproportionately large legs and an easy strut.

Myriam Farshadi, a twentysomething Persian from Tehran, who had modeled her way through graduate school in Los Angeles and had only recently relocated to New York for Merkin’s appointment, sheepishly filed in after them. She was hoping to make tenure within the next three years.

“Weird tension here today,” said Bowman, only twenty-eight and quicker with his tongue than with his brain. He’d done time at Harvard and then at Magdalene College in Cambridge, where debating was easy, fearless, and as natural as trained rowing on the Charles.

Geraldine bunched up her face in a mischievous smirk.

Lorna ignored the comment and instead reviewed her notes, the agenda for the meeting.

The staff assumed their jocularly fearsome circular seating formation. Oh, these people.

Dr. Chen said: “Your last paper, the one just published in Junk & Noise, was oddly confident in its assertions about homoerotic imperialism and role play, Dr. Truman-Hall.”

“Why was the confidence odd, Dr. Chen?”

Dr. Chen crossed his legs and spoke with a raised chin. “Well, there’s not been a sufficient amount of data collected, yet. It’s still just theoretical.”

Lorna sighed. “But that’s what we are. Theoreticians. Our work is rooted in observation and analysis. It’s also largely guesswork. Creative guesswork.”

Dr. Chen’s dismissive smile, marked by bushy inverted eyebrows and dimples, caused Lorna to reflexively sneer. “Dr. Truman-Hall … Lorna … Our students keep interrupting class to discuss the YouTube video … it’s been over a week and it’s not going away.”

Dr. Farshadi sighed and, a little bored, thumbed through her students’ research essays, which she had been grading before the meeting diverted her. These gatherings were always sullen and tense, not unlike a funerary repast, she thought. And it being the first since the social media bombshell, it was better to have work on hand for the sake of healthy distraction

Lorna took a breath before speaking. “It is the white elephant in the room today, isn’t it? I get it, I do. But, really, what do any of you want me to do about it? I was just doing my job. I have no interest in being that kind of a teacher, who watches her Ps and Qs, censors herself, pleases the students and their parents and the community and the stakeholders. If I wanted to become that kind of teacher, I wouldn’t have earned my fucking doctorate and I would have resigned myself to teaching high school or kindergarten! Do you have any idea how many emails and letters I’ve been receiving? People calling me a cunt and a bitch and a self-loathing woman, a gender traitor! A sexist and a misogynist? Do you?!”

Lorna was taken aback by how angry she’d become. It had crept up on her the more she talked, the more she thought about how useless and compromising the entire affair had been.

“And look!” she ventured on.

Lorna grabbed her laptop off her desk, smashed away nervously at the keys, and then spun the computer around for her staff to see the video playing on Vimeo:

Two suited women, both with close-cropped hair and chalky white skin, spoke chirpily about Lorna, the footage of the infamous video on mute in the background. It was MSNBC and the talking heads were self-satisfied in their tone and regal in their miens.

“She should be censured,” said one woman. “Merkin has a moral and ethical responsibility to patrol and discipline their own.”

“I think she’s a dangerous dinosaur who’s undermining the Democratic party,” said the other. “And in the end, she’ll just end up empowering the Republicans. This is exactly what they want.”

Lorna stopped the clip, put her laptop on the desk, and combed her hair back behind her ears. Her wide, handsome face, often with little makeup and dark eyes with thin lips, wasn’t completely feminine with her hair set back.

Geraldine fixed her stare on a Victorian weathervane and Colonial scale of justice, both patina laden, resting on a mantle close to Lorna’s desk. Her office was stately that way, thought Geraldine. Quintessential in its Ivy League trappings.

“This is what we’ve been saying, Lorna,” said Geraldine. “It’s becoming a bigger story and it’s not fair for us to have to bear the brunt as a department.”

“It’s not nice, the things I say, and I know that, but nice isn’t something I aspire to be. Right is. I am only interested in being right, Geraldine.”

Geraldine made a cartoonish, goofy face. A face that laughed at others, a face to be laughed at. “And do you really think you are with all of this?”

Lorna’s eyes widened in faux cheer. “Bowman, your ancestors were from England, right?”

Dr. Bowman’s grin caused him to redden. His powder blue eyes even sparkled. “English, through and through.”

Lorna nodded, played with her earring. “Chen, your family are Cantonese, though they moved to Beijing when you were in first grade, no?”

“Yes, that’s right. Though we went to Hong Kong probably once a month to visit family.”

That time her father caught her masturbating to a boxing match when she was fourteen. Mother had dismissed it as healthy. He was supposed to have been the more progressive of the two, but it was she who better understood the ways of a young woman’s impulses. What excited. What satisfied. She spared Lorna a discussion. Lorna would graduate to horror films and BDSM videos she’d find on gay websites by college. Popular, respectable teen girl and women’s magazines would never explore these impulses. They were proclivities that no one wanted to touch, consider, or watch.

Lorna stopped fidgeting with her earring and said to Bowman, as though they were faculty gathering friends: “They left, though, because they had trouble with England’s ethnic influence, right?”

Dr. Chen cleared his throat and mumbled when he spoke. “Even after the handover in ‘97, it still lingers. Like a stain.”

Bowman’s eyes narrowed as he chewed his cheek.

“Like a stain,” repeated Lorna. “What kind of a stain?”

Dr. Chen’s compact body with aged muscle seemed to grow bigger as his childlike face took on a hardened countenance. He chuckled and pretended to annotate an article.

Dr. Chen, into his chest: “They arrived in 1841. It was a long time, their stay. They had occupied for a long time, Lorna.”

Lorna tapped her pen softly against her bare left leg, slung over her right. “You’re aware of the emasculation campaign that some British soldiers decided to spearhead clandestinely, aren’t you?”

Dr. Bowman sat up, jaw clenched.

Dr. Chen frowned. “I’m not familiar, no.”

“Apparently, the young English soldiers of a small village outside of Hong Kong, I believe not far from Kowloon Bay, had decided that to make the Cantonese men easier to manage they’d have to break them first of their pride and pesky tendency toward self-defense.”

Dr. Bowman’s sat up awkwardly as his stomach tightened. On his knees, Dr. Chen’s fists balled.

“These young English soldiers would systematically pick out the strongest and most dominant men in the pack, the troublemakers, the agitators. Mostly fishermen or dock workers. Real brutes. And they would ritualistically rape them in front of the whole community. Shaming them. Feminizing them. Many committed suicide. Many others ran away. The British had their reign. As you said, Dr. Chen, it had lasted for one hundred and fifty-six years.”

Dr. Chen snarled and when he spoke it was with a big, wet lump in his throat. “Fucking Limey bastards.”

“Whoa there!” exclaimed Dr. Bowman who stood up on a nervy impulse, dropping his folder and notes to the floor.

Dr. Farshadi gasped and instinctively covered her breasts and closed her long tawny legs.

Red obscured Dr. Chen’s vision and he shook. “Piggish white people. I could go on!”

Dr. Bowman snapped out the epithet, and the word could not be unsaid. He knew he erred when he saw the faces of Dr. Farshadi and Geraldine, both of whom were wearing expressions of repulsion. But Dr. Bowman had only reacted and lost his sense of station, of place, of propriety.

Dr. Chen also snapped, but his explosion was not verbal. It was physical and before he realized what he was doing he had already leaped to his feet, thrown a knee in Dr. Bowman’s ribs, causing his pillar-like legs to crumble, another into his face, and was currently on top of him striking with a crazed repetition the boyish redhead’s swollen mouth, making it bleed.

Lorna’s desk had been knocked over, two of her plants were left smashed, and at least one chair-leg was cracked. But she didn’t care about any of that. In fact, she could barely contain her glow, the grin too bright to shade, and it shone on Dr. Chen, who was panting and revealed the faint outline of an erection when he stood. It shone too on Dr. Farshadi, who had a hand pressed against her right breast and another against her mons veneris.

Geraldine was breathless and flush, her hands out of view.

Nothing like this had ever happened, though Lorna had always hoped and meant it to. But it kept on happening, and delightedly Lorna wondered how’d she work it into her next book without condemning anyone at all. She thought of Plato’s reverence for the Olympians.

Dr. Bowman groaned and coughed up a tooth and some of his lunch as Dr. Chen adjusted his tumescence and the female professors endeavored to steady their breathing. Lorna’s inconvenient insights settled on the room’s queasy inhabitants with an uneasy weight. Though it hadn’t solved any problems, she was satisfied with the support of her thesis it had offered.

Then it was over, for now. It would prefigure future events, Lorna was certain.

THE NEXT FEW DAYS would bring about more Internet-triggered seismic spasms. It manifested next at home. Risk policed the bar and drank too much. Lorna was on the couch and replayed the events of the barbarism in her office. She’d thought about it often since the melee.

“So, it seems that the board has a problem with my behavior,” said Risk, lumbering over a series of wine traps, gripping a bottle of beer.

Lorna was on her second highball. “No kidding?”

“They took issue with how I conducted myself during the team-building challenges and, you know, that I videotaped it, put it online. Fucking shit. They think it reflects badly on me and as an extension on the network. Whatever. Small, mediocre …”

How he conducted himself: pulling Dominick’s ankle as he climbed the tall, plastic rock wall, causing him to dislocate a knee. Tackling him into poison ivy near West Point after he was clearly going to reach the finish line first. Kicking him in the balls during what had been a friendly Muay Thai sparing session. And then electing to upload all of these juvenile, violent shenanigans onto an internationally-accessible website.

“And the Remington Associates, they’re, uh, not happy either. So …”

“So, they’ve both let you go, then? Fired you?”

“Yeah, but not without a healthy severance … and then there’s our savings, right? I mean, we’re fine. Just fine. And this means that maybe we can seriously move forward with Spain.”

Move forward with Spain. As though it were wedding plans or a military campaign. Lorna hadn’t said too much more after his blasé pronouncements.

Why had she ever thought their lives were anything but contingency? Once Spain had seemed like a romantic fling held at bay while they found themselves. They’d never used the phrase found themselves. But that’s what they were doing because both of them were now completely lost. The city was already forgetting them.

She retreated into her home office, smaller than the one at Merkin by half, and checked her emails. The home office featured no plants, no posters of any Adonis or warrior. Just stacks of papers and shelves lined with books.

So many emails from former students and colleagues who wished to express their disfavor or support, scolding and sympathy.

Though at fifty-one she wasn’t all that old, Lorna was dazzled by how quickly the world had changed and how far behind it had left her. The new guard deemed her a relic of a primitive age. Not long ago her theories would be fodder for dinnertime discussion, stimulating classroom debate, and gentlemanly cross-examination in chambers of critical analysis. Now she was just labeled a cretin and a monster.

Multiple requests from legacy media, top brands wishing for interviews and profiles. Lorna would consider, but ultimately ignore the opportunities. She had no need to clear her name or clarify anything she’d said. The email from the publisher of The Wanton Feminine wouldn’t arrive for another week. It would remind her of the morality clause in her contract and cancel the publication of her book, citing “too-tempestuous social headwinds”. They’d allude to the Twitter storms, the FaceBook fusillades, and the coverage on the 24-hour news networks, excerpting the comments and posts, likes and emojis.

BUT she was surprised by how grateful she felt for the momentary attention, negative though it mostly was. So what if the suicide requests and insults had started to chip away at her? She was relevant, again. Perhaps it was time to leave. Start over. Find a place in the world where they didn’t martyr speakers of unpopular truths.

And then an official letter from Sherlyn Lopez, Merkin’s director of human resources. Lorna urgently opened the email. She stared at the screen, rereading the words until her eyes strained, until they made sense. It took many minutes before they did.

Dr. Hall-Truman,

We regret to inform you that your term of employment at City University of New York Merkin has come to an immediate end. Due to your violation of our employee code of conduct Section 4.b) we have no choice but to end your employment with us.

You have until the end of November 2019 to clean out your office and vacate the premises. If you do not comply, your belongings will be packed up for you and you will be escorted off the premises by our security team.

Your courses for the remainder of the Autumn 2019 semester have been canceled and all students have received full refunds.

We thank you for your service to City University of New York Merkin and we wish it didn’t have to end this way.

She could hear realtors picking up the phone and calling to ask if it was true, and how soon would their place be available for staging and showing.

—

Brian Alessandro holds an MA in clinical psychology from Columbia University and has taught the subject at the high school and college levels for over ten years. His work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize twice and the Independent Book Publisher Association Best New Voice Award. In 2011, he wrote and directed the feature film, Afghan Hound, and has adapted Edmund White’s 1982-classic “A Boy’s Own Story” into a graphic novel for Top Shelf Productions. Brian currently writes literary criticism for Newsday.

Brian Alessandro holds an MA in clinical psychology from Columbia University and has taught the subject at the high school and college levels for over ten years. His work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize twice and the Independent Book Publisher Association Best New Voice Award. In 2011, he wrote and directed the feature film, Afghan Hound, and has adapted Edmund White’s 1982-classic “A Boy’s Own Story” into a graphic novel for Top Shelf Productions. Brian currently writes literary criticism for Newsday.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)

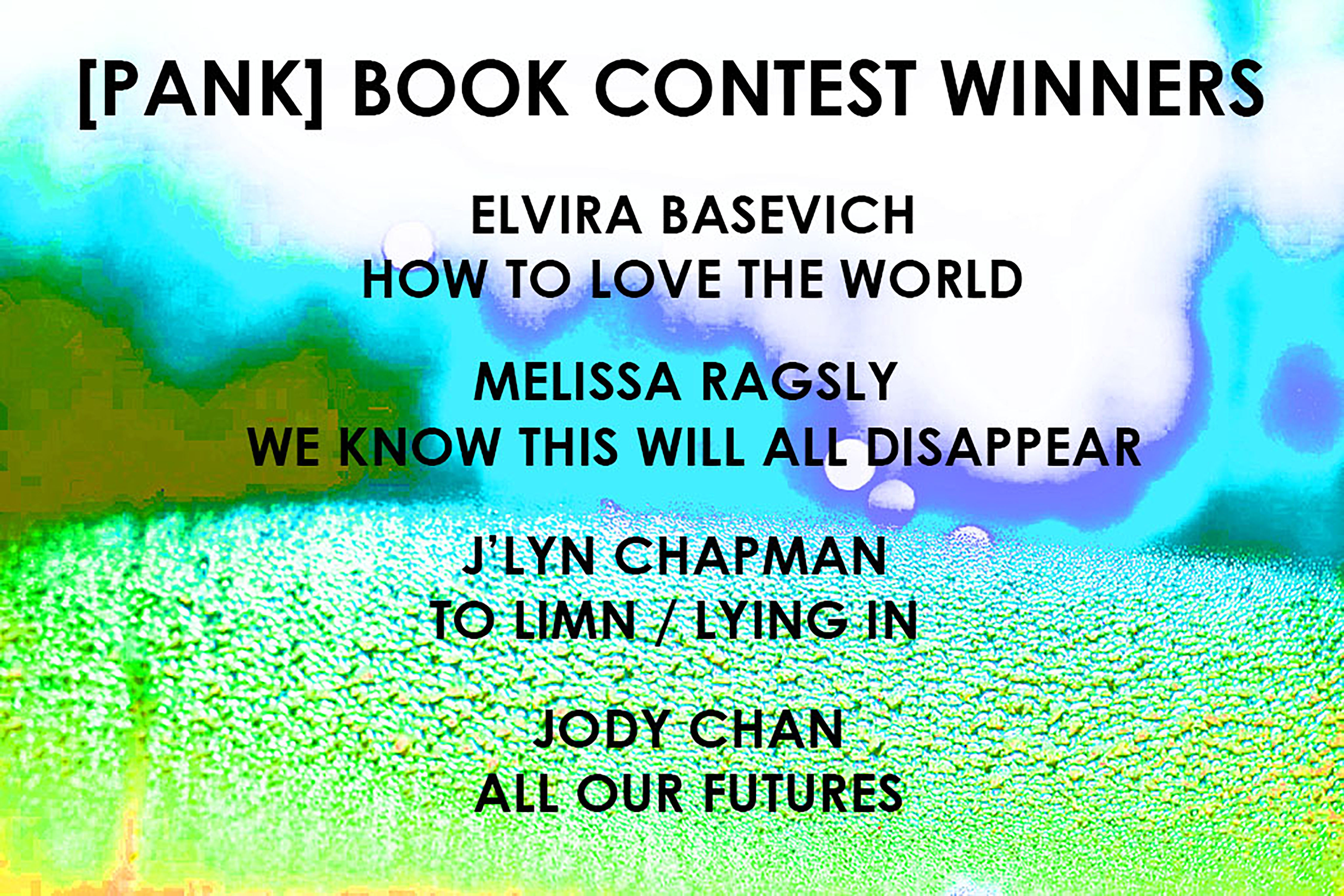

(Autumn House Press, 2019)

(Autumn House Press, 2019) HADLEY MOORE’s fiction has appeared in McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Witness, Amazon’s Day One, the Alaska Quarterly Review, the revived december, the Indiana Review, Anomaly, Quarter After Eight, Confrontation, The Drum, Midwestern Gothic, and elsewhere. She is an alumna of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College and lives near Kalamazoo, Michigan.

HADLEY MOORE’s fiction has appeared in McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Witness, Amazon’s Day One, the Alaska Quarterly Review, the revived december, the Indiana Review, Anomaly, Quarter After Eight, Confrontation, The Drum, Midwestern Gothic, and elsewhere. She is an alumna of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College and lives near Kalamazoo, Michigan. Brian Alessandro holds an MA in clinical psychology from Columbia University and has taught the subject at the high school and college levels for over ten years. His work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize twice and the Independent Book Publisher Association Best New Voice Award. In 2011, he wrote and directed the feature film, Afghan Hound, and has adapted Edmund White’s 1982-classic “A Boy’s Own Story” into a graphic novel for Top Shelf Productions. Brian currently writes literary criticism for Newsday.

Brian Alessandro holds an MA in clinical psychology from Columbia University and has taught the subject at the high school and college levels for over ten years. His work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize twice and the Independent Book Publisher Association Best New Voice Award. In 2011, he wrote and directed the feature film, Afghan Hound, and has adapted Edmund White’s 1982-classic “A Boy’s Own Story” into a graphic novel for Top Shelf Productions. Brian currently writes literary criticism for Newsday.