~by Kate Schapira

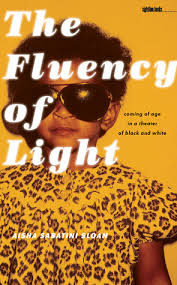

Sightline Books: The Iowa Series in Literary Nonfiction

128 pgs/$17.95

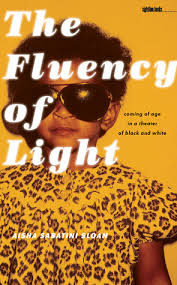

Discussions of whiteness and blackness in America all too often devolve into a series of platitudes. In fear, fury, insistence or exhaustion, statements grow more and more categorical; poetry, complexity, and improvisation leak out. Aisha Sabatini Sloan’s collection of essays—facets of memoir gathered around, crystalized and refracted by works of art and bodies of music—works to put them back.

Sabatini Sloan orders one of her most intense and far-ranging essays, “Silencing Cassandra,” around riots in London when a police officer killed a young man named Mark Duggan. She quotes a BBC interview with a black Londoner named Darcus Howe, who says of his grandson, “’I asked him the other day, apropos of the sense that something was seriously wrong in this country. I said, “How many times have the police touched you?” He said, “Papa, I can’t count, there have been so many times.”’Inaudible remarks continue.” What sound can include both the inability to speak and the refusal to listen?

Sabatini Sloan turns to P.J. Harvey’s howl of an album Let England Shake, Anne Carson’s essay “The Gender of Sound” and playwright Joseph Chaikin to show these riots not just in the context of their history but by the light of works that “[let], like a needle in the vein, the blood out of a sick body, extracting a kind of poison”; that make, according to an unnamed Jamaican musician she quotes, “a sufferer’s sound.” “Silencing Cassandra” also draws glints from Revenge of the Nerds II, the Skatalites, Scared Straight, Secrets and Lies, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Malcom Gladwell, Graceland, Parenthood, and dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson; photographers Lorna Simpson, Charlie Philips and Arnet Francis; writers on music David Katz and Les Black. Writing, in a book about race, of a riot with origins in racism is not unusual or unfraught; what has power is that Sabatini Sloan shows how this is not news, how these works throw off reflections, half-tones, shudders, resemblances we could see if we were watching, hear if we were listening. Continue reading →

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)