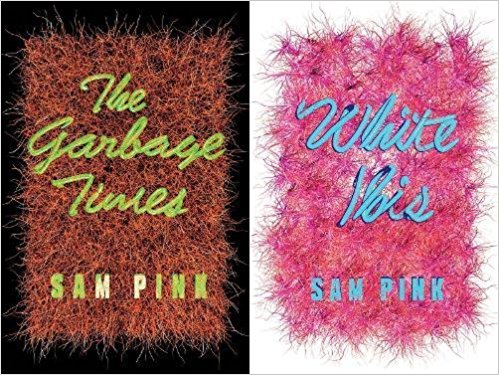

(Soft Skull Press, 2018)

REVIEWED BY CHRIS VOLA

__

During the past few years, Chicago novelist, poet, and indie-lit cult hero Sam Pink has also become a prolific artist. The hundreds of paintings, drawings, and collages – which he sells via his Instagram and Twitter pages – are all beautiful exercises in abstract chaos: forcefully wrought swirls of bright blues, yellows, and pinks, jagged, black-lined geometric patterns staggering the foreground like cell bars, vaguely sinister anthropomorphic shapes lurking in the background, the sense of something monstrous just barely held back in the moment before it finally bursts free, a feeling that’s amplified by the pieces’ bizarre, occasionally violent titles like “The Ache is Beginning to Yell and I Love It” and “Siccing Myself on Your Ticker.” It’s an idiosyncratic cacophony that longtime Pink devotees will find intensely familiar.

For the last decade or so, Pink the writer has developed a similarly caustic yet addictive voice, first in prose poems and short stories, and later in a series of short novels starting with 2010’s Person. The gritty, profane, and always hilarious tales chronicle the exploits of, ostensibly, the same young, unnamed narrator as he navigates various unsavory Chicago neighborhoods, moving from filthy apartments to dead-end jobs to casual liaisons featuring deranged street folk with names like Spider-Man and Sour Cream, all the while unleashing antisocial one-liners (“The thought of calling off work is like the thought of suicide, just nice to think about”; “My ideal date would involve painful silence. My ideal date wouldn’t involve me”) that are as extreme as they are blackly candid. It’s never so much what he does that makes him so appealing – although talking smack to a tarantula named Roy or burning down a future ex-girlfriend’s trampoline does sound like quite a morning – it’s the simmering, bullet-sharp shape of his inner monologue, a coagulation of thought-snippets and pleasingly vile fantasies that shirk slacker clichés in order to honestly, unflinchingly critique and dismantle what he believes are society’s countless accepted absurdities in the hope of creating something better. An ideology best summed up during a moment in Rontel (2013) where the narrator is watching his brother snatch an old kitchen appliance someone’s left on the street and, without any premeditation, toss it off a nearby building:

The microwave hit the ground a few feet in front of me and compressed a little, sending out small pieces.

It was great!

Always felt like, if I could pause time, I’d just go around and break everything then un-pause time, leaving people unharmed but everything else broken, even clouds, mountains, and the sun, maybe a fish or two as well.

Here, as in much of Pink’s oeuvre, a prayer for violent, planet-level deconstruction is tempered by an unsentimental yet powerful need to be a part of the world and to find something to love amidst the self-imposed exile. But this need is rarely if ever met. Each new book ends with the narrator still mired in the same minimum-wage squalor, a lack of narrative momentum, that, while not necessarily detracting from the quality of the work, can sometimes feel a bit redundant. All of that changes by the end of Pink’s latest two-volume release, The Garbage Times/White Ibis, in which the narrator finally manages to uproot himself from Chicago, a surprising shift that results in the author’s most complete, engaging, and funniest work yet.

The Garbage Times picks up more or less where 2014’s Witch Piss leaves off. The narrator finds himself trudging through another frigid Chicago winter wearing a secondhand coat “the color of drug shit” and working as a barback/bouncer at a dive bar populated by the usual assortment of degenerates, prostitutes, and Vietnam veterans with bowel-control issues. His journeys to and from work, and his frequent hellish descents into the mold and trash-soaked basement of the bar are peppered with his standard, comically awkward social interactions, scathing analyses of children’s books featuring a movie-star dog on a skateboard, and relatable observations about the inevitability of literal and metaphorical trash: “There was always dirt. There would always be dirt. There was no escape from dirt. If you remained in motion your whole life, it still buried you.” While there is still an occasional glimmer of ironic hopefulness amidst the filth and faux-gleeful self-disgust (“acknowledging in advance the possibility of defeat so as to prevent defeat”), the first chapters of the novella seem to be possessed of a greater weariness than in any of Pink’s previous efforts, the sense that “bleeding from all these invisible wounds” has begun to take a serious toll that no amount of posturing or escapist fantasies of theoretical violence can fix, a feeling that is only amplified after a tragedy involving a beloved pet. However, in trademark style, the narrator forgoes any kind of real self-examination and buoys himself with a small streak of luck (in the form of a free sandwich) as a familiar inertia seeps into The Garbage Times’ final pages, punctuated by an imagined kiss so powerful it assassinates the sun. In short, the book feels like another weirdly entertaining pit stop on the Sam Pink highway to nowhere, which makes the opening of White Ibis all the more jarring.

The second novella begins with the narrator suddenly and inexplicably escaping a Chicago apartment “that owes us nothing” with his new girlfriend and new kitten in tow, with only the vague intimation that he is ready for “the next level.” They drive to Tampa and move into the girlfriend’s brother’s vacant house and the narrator takes to exploring a landscape as beautifully lush as Chicago is desolate and dirty. Animals have always played an integral role in Pink’s books, offering a welcome respite from “the things with real teeth and power. The monsters. The real motherfuckers” – those infinitely flawed sufferers of the human condition. Amongst all the exotic Florida wildlife the narrator encounters – alligators, bobcats, snakes, lizards, his girlfriend’s brother’s loveable mutt named Bam – nothing is more mysterious than a gangly white ibis that can be found constantly pacing at the end of his driveway. The bird takes on an almost mythological yet undefined significance, a symbol that both befuddles and enthralls him.

But no amount of birdwatching can save the narrator from being dragged to numerous family social functions with his girlfriend, where he is forced to interact with exclusively “normal” people for the first time, experiences that are more harrowing for him than the darkest bum-strewn alley. After much internal gnashing, he forces himself to survive children’s birthday parties, country-club happy hours, and unexpected visits from needy relatives – a world he has spent years avoiding – by diffusing the utter insanity of contemporary suburban life with dark, witty humor and facing his many fears with a greater depth than ever before. While he still allows his manic imagination to go rampant – a troop of cute Girl Scouts at a sleepover party becomes a terrifying cabal bent on global enslavement, middle-aged men in boating shorts/shoes morph into lethal predators – he never allows himself to go completely off the rails, as he has many times before.

In earlier Pink books, the narrator has always felt more like a mouthpiece for his ideology than a fully fleshed protagonist, a faceless everyman whose sharp-tongued misanthropy is powerful enough to be relatable without any kind of relevant backstory. But relatability is not the same as intimacy. White Ibis offers character building on an unprecedented scale for Pink, perhaps because the narrator’s new environment is more conducive to exposing more of himself, or maybe he’s just less guarded as he gets older. Regardless, it is fascinating to finally get a glimpse of his previously undescribed life as a visual artist and fiction writer and bear witness to his many insecurities and perceived failings, but also his obvious pride in being able to connect with others, most poignantly in the form of an email from a transgender fan who is able to ward off suicidal thoughts with the help of the narrator’s previously published novellas. The last chapters mark an uncharacteristic but welcome transition to relative domestic tranquility, punctuated by one last encounter with the narrator’s favorite bird. The white ibis isn’t a disconcerting omen, he realizes, but rather a profound reminder to never forget where he comes from, and to more objectively accept all of the diverse facets that comprise his personality: “The white ibis stood in place for a second, eyeing me, then flew a little bit away – which is probably a good rule for how to behave around anyone…I watched it, knowing then that we were never meant to be friends. We were too similar.”

Naturally, art imitates art, and the perception of an individual piece can be directly influenced by an examination of the artist’s larger body of work. Consider Pink’s recent painting “A Group of People Vaguely Operating as One” (which was painted in the author’s home in Tampa, and which, full disclosure, currently hangs in this reviewer’s living room): at first glance, your eyes are pulled in any number of directions, overwhelmed by the green and yellow constellations of seemingly random swirls and pulsing lines, a jumbled dystopian cityscape collapsing on itself. But as you focus a little harder, you begin to notice another layer to the piece, a vaguely humanoid/robotic figure near the center, arms raised and seemingly at peace, merging with the various patterns and shapes that no longer seem random but somehow part of something larger, something indefinite but strangely hopeful, and you realize that the painting’s title isn’t an ironic joke. The first word that comes to mind is one that is rarely, if ever, employed when discussing Sam Pink: harmony. The same feeling permeates the final pages of White Ibis, showcasing a battle-toughened, confident writer at the top of his game, no longer shackled to the same cyclical narrative, and with no inclination as to where he’s headed next. It’s a sense of intriguing uncertainty that one imagines is as refreshing for Pink as it is for the reader.

__

Chris Vola is the author of two novels and a collection of stories. He writes and bartends in New York.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)