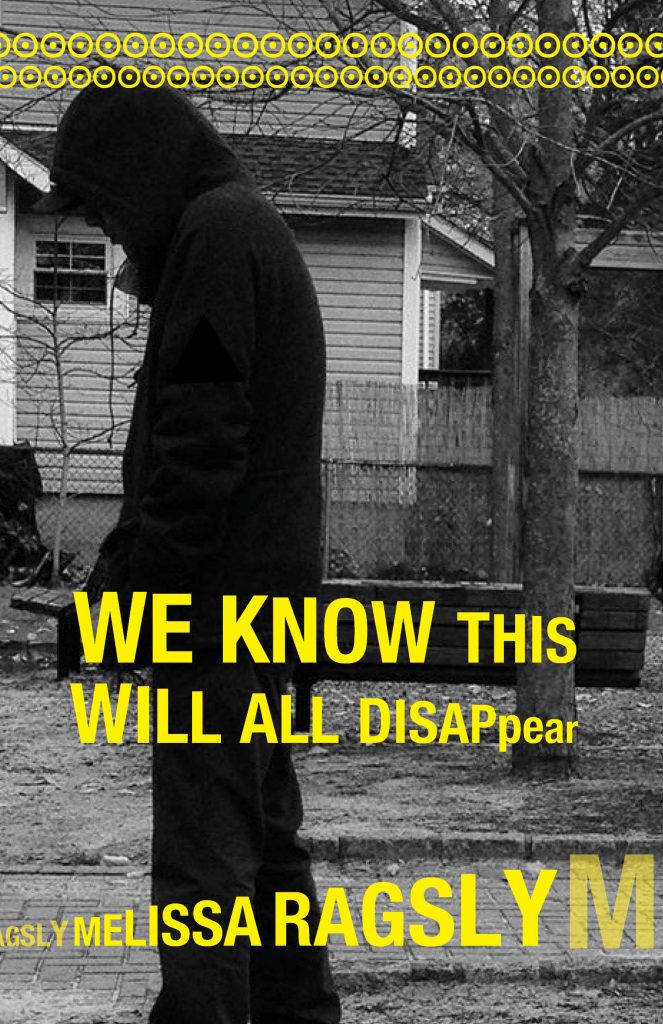

PANK Team Member Emily McLaughlin sat down with our 2019 Fiction Contest Winner (as selected by Gabino Iglesias) and 2020 PANK Books Fiction Contest Judge Melissa Ragsly to discuss the incredible stories in her debut collection We Know This Will All Disappear.

Emily McLaughlin: A strange time to have your book come out . . . What has the book launch during a quarantine experience been like so far?

Melissa Ragsly: Honestly, I have nothing to compare it to, but it’s definitely felt restrained, happy to have it out in the world and a network of friends and writers to share it with. I don’t think it can replace some of the traditional elements of a book launch. A launch in quarantine might be less expensive, no traveling required, but I think it’s limiting in terms of who has access to a book. If you are promoting through your own social media, there is less chance of breaking through to someone new. I’ve done some virtual readings and some more are coming down the pike, but I’m also imagining next summer, I’d be able to do more in-person readings in bookstores and bars. The intimacy of what I write seems best experienced in dark rooms, not screens. Maybe it would be best if I recorded bits of stories in sound files instead of Zoom events. I’d rather you hear these stories in that context. It’s been a challenge to think creatively in any context as our lives have changed so much in the past few months. Adding to that pile by coming up with solutions to creatively market a small press book? It’s surreal.

EM: When you read “Bio Baby” for the book’s launch at AWP, does feel of another lifetime. That story is even more moving read aloud. Since then, the more time I have spent pouring over the sixteen stories here, the more I am floored by how perfectly crafted and polished each one is, how you pack so many exquisite details into short spaces, how each one performs the tricks only stories are capable of. I could bring each story into my creative writing class and hold up as an example to students: “this is how you write a short story” and then point out, and this is how much work you can expect it to be. Can you walk us through your drafting and revision process, maybe how much time you spent on revising one story versus another?

MR: I’m not one of those people that writes a whole draft through knowing I need to go back and fix everything. I like avoiding the fixing. I start a story with an idea or an image, a feeling really, so I don’t really know what it’s about or where it’s going. I write a page, print it out, edit it for voice and in doing so, usually find the next beat. Write that, repeat until I get to the conclusion. For flash, sometimes, that conclusion or the point of it is hiding in the first draft, but I still try to coax it using the same process. Drafting feels very back and forth, like playing an accordion.

EM: And how do you decide that the story is complete, ready to send to journals?

It’s difficult to write a story and think it’s perfect and it being done is not the same as being perfect. So you just have to accept it’s done when it feels done. When I put it down and pick it up again and it still feels done. It can try to fool you into thinking it’s complete, fake you out a bit, or maybe that’s something that happens to me because I’m lazy and I just desperately want it to be over. You write it and then you have to sneak up on it again after a few days. It would terrify me to write straight through and then go back to the beginning and tackle all its mistakes from the first paragraph. I need to know some of that work is done so that when I am done with it, it’s ready to go out on submission.

EM: I love so many of your lines. This one, in “Napkin of Death Metal” is amazing: “Sometimes just sitting in a bar makes men think girls are waiting for them to come. A girl is a frozen toy mouse marking time until a paw bats them across the floor.” This seems like the kind of line a writer gets in her head and thinks, I have to put this in a story. But maybe not?

MR: That line was added on the last pass through. To go back to the earlier question, how do you know when a story is ready to send—without that line it wasn’t ready. Sometimes a line can only come out once you know better what the story is about and you can either say it straight out, or you can try to allude to it. A line like that is almost for me as much as for a reader, I’m telling us both what it’s about.

I think that the only time I came up with a line first before the story was the opening line of Bio-Baby. “On the morning of my abortion I watched a Teen Mom 2 marathon.” That was going to be a completely different story. More essayistic, more personal and it turned out the complete opposite. But I kept the line.

EM: Each story seems to do its own thing, invent its own way of how it’s going to tell the story, and compiled together, this gives the collection a sense of unpredictability, excitement. Yet there’s a feeling of stability reading them, in that you know each one is going to deliver some kind of feeling of peace. How did you assemble the stories, or envision the structure for the book?

MR: In ordering the collection, I went with intuition, all feel, but the specific feeling I tried to create was something like a wave, so in and of itself, something peaceful, yet unpredictable; delightful, yet destructive. Something whose strength can surprise you. Having both longer stories and flashes, you just want the pattern of them to make sense. You want some pieces to feel like a breath, some like an anchor. A table of contents is like this puzzle you get to play with, shuffle around the order. I did that until I felt I’d translated that feeling of tides.

EM: The majority of the collection uses first person narration versus the five stories told in third. Did you ever feel pressure to write in third for variety’s sake? Does one seem more natural to you than the other, and what do you notice changes about the story when you write about the character in third? For example, in “No One’s Watching” why did you ultimately decide to approach the character from third, not first, as opposed to a story such as “Bio Baby?”

MR: I can full-throatedly say I prefer first person. Writing it and reading it. I want the intimacy of it. When I hear criticism of it, that its navel gazing or self-indulgent, I don’t get that at all because it’s like criticism of first person seems to come from people thinking it’s someone talking to themselves in their own head when to me it’s someone talking to someone else, it’s like a one-on-one confession. It feels like the only way a writer and a reader can bond. I’m also just a very one-on-one person. Third person feels so group to me. Like no one is being honest here, it feels polite, like as if not to offend. I tend to think of third as more appropriate for longer, more traditional stories, almost as a default.

“No One’s Watching” was very different on the first draft. The story as it is now was the flashback in a longer story, so third made it feel distant from the rest of the story. I kept that, I think, because the story itself, emotionally deals with distance that isn’t quite understood by the characters yet. It’s almost like an origin story, maybe you’ll find that character again later in a first person story dealing with the ramifications of those feeling and events in this one.

EM: All of your stories have these meditative poetic lines buried in the paragraphs, as if you or the characters are humble, trying to hide them. Just one example, I could pull so many out as examples: “I wanted to know I had a place that I wouldn’t have to exist for anyone but myself.” Is this intentional to not draw attention to the writing? Does more self-congratulatory writing bother you?

MR: I think if you reveal something vulnerable, or a truth that you realize, you do it in a non-calculated way. Your body just opens up to the truth and it’s a portal that can slam shut quickly. Most people stumble on the truth and then can turn their backs to it without realizing it or wanting to, because it appears randomly in a moment. It makes sense to have those moments appear and then the characters move on. It’s not conscious on a writer level, but more on a character level. I think I write about the types of person that thinks this way. Like, there it is, I see it, and I’m going to blink and it might not be there when I look again.

EM: That’s a very nice way to put that. So what was the first story you wrote here?

MR: “Tattoo”. That was started probably in 2014? 2015? And then most of the longer short stories after that. In the last year, it’s been mostly flash. Flash really opened me up in a way longer stories didn’t. They feel rule-less or more freeing in their containment.

EM: Is there a story you feel closest to?

MR: It changes. At the moment, I feel a connection to “Napkin of Death Metal” and “All You’ve Heard is True.” It goes back to the idea of flash. I think there’s so much of me in both of them and if I tried to write these as longer pieces, they would feel diluted. I feel like these are four-dimensional. I like to joke my favorite is writing in the fourth person and I think this is what I mean. I think!

EM: So obviously you are writing a novel in fourth person.

MR: I am writing a novel and I have been for many years and I haven’t quite cracked how to do it. I know people have opinions on how to do it. And many people have done it, so I know it’s possible. But I haven’t yet!

EM: How do you approach keeping your character’s level of perception of her world consistent in a novel versus in a story? (to clarify: do you struggle with interiority in the form of novel versus in the story?)

MR: I actually started writing this novel in third person and it never quite worked. I switched to first but then it wasn’t working then because it was about more than one person, so I found the groove using several different POVs. And while I have not completed this one, of course I have already started formulating the next and I also am thinking of it as several different POVs. I feel comfortable with telling the story that way. Multiple POVs feels like you’re telling an oral history and I’m obsessed with them. Like reading a documentary. And yes, I do think that is also a way for me to keep handle on the character’s interiority, because I’m finding ways to use different character’s thoughts and happenings as companions and comparisons to others. In a way, it feels a little like trying to formulate that collection order. Finding ways for the story as a whole to feel like teeth on a zipper gnashing together. And again, it’s not always about interiority for me, so much as the conversation between the character/writer and the reader. The characters are not talking to themselves so it’s more like an open interiority. Like the roof’s off the room.

As far as being productive, lock-down with children has made me feel like my hands are tied. But the goal is to have it finished this year.

EM: That’s ambitious — even for a writer not locked down with children!

I was trying to figure out how you wove such suspense into the story “Lilith,” when we already know the ending at the start – Lilith is not coming back. Can you tell me your secret? When writing this one, did you find yourself not wanting to conform to tropes about missing women? Is this why the character thinks in terms of time tables, lists of facts, even math equations here?

MR: I wanted there to be an element of logic as a way of containing your feelings. Some people don’t know how to feel. But they do anyway, so what are ways that feeling emerge? I was obsessed with thinking about those crime solving brainstorm boards. Pictures of people and places connected by strings. I wanted to play with how logic and feelings can work together.

This story came together on one of those days where I just felt depressed and like I couldn’t think and I just felt like watching Dateline which is like a once a year, falling into a depression, brain-clean. Just sit there and watch stories about murder and crime and how people figure out these puzzles. I saw one about a missing woman. She was never found. It’s a pretty famous one, although I can’t remember her name. You didn’t get the benefit of the arrest at the end. A question you don’t get the answer to. It was frustrating for me, sitting there depressed on the couch, not knowing what happened to her. How is it going to feel for someone who is actually invested. I just wanted to try to understand how that felt. I felt like there were so many questions within my family that were never answered. Or answered much later. So I also wanted to think about how sometimes you can’t have an answer, you can’t solve something and so how do you move on? Do you make up an answer and accept it or do you keep trying to solve it? Or do you just get stuck?

EM: Do you want to tell us about the book’s cover and your vision for how this melancholy image correlates to your title?

MR: The cover is a picture I took that is actually larger. You don’t get to see the whole image and the whole one is actually more hopeful. That hooded man — that’s my husband and that’s a park in our town and one of our kids was in the swing. So, the sort of gloomy hood of death is next to a kid in the swing, but turned away. So it’s actually kind of funny.

The black and white, the hunch, yes, it’s melancholy as I think my stories are, but I do think that the title also reflects an acceptance. Everything will disappear in time, but that means the bad things too. Any pain or crisis, lockdown. All that will be over at some point. The effects of all the things we live through, good or bad, remain. That’s what stories feel like—the stubborn invisible.

EM: How did you maintain confidence or stop yourself from succumbing to self-doubt when working on this project, or maybe your next project? Any special powers you tap into in order to dig your feet in?

MR: I don’t have self-doubt about my ability, but I am so lazy when it comes to time and I’m absolutely a late bloomer so it doesn’t bother me to take a long time to get a project done. I feel like if it’s worthy and meant to be in the world, I will finish it.

Any writer’s special power is reading. But I’m a bumble bee reader. Maybe because my name means “honey bee” or I feel like I’m missing out if I don’t, I have to be reading like 15 books at once. The best thing is to have a big pile of them and read 10 pages in each until you cycle thorough and start over again. It’s kind of like flipping through channels. I look for similarities and connections and see if the different books speak to each other in some way. Yesterday, 2 things I read mentioned Zeno’s Paradox. I’d never heard of it before and then twice in one day, Zeno and his philosophies come into my hands. Reading and thinking give me the confidence to write because I want to be that brain exercise for someone else. Just a link in the chain.

ORDER WE KNOW THIS WILL ALL DISAPPEAR HERE

________________

Melissa Ragsly is a writer living in the Hudson Valley. Her work has appeared in Best American Nonrequired Reading, Best Small Fictions, Iowa Review, Hobart, and other journals. More can be found at melissaragsly.com.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)