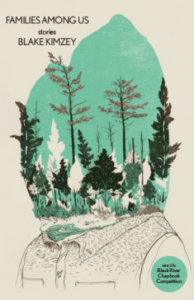

40 pages, $8.95

Review by Thomas Michael Duncan

In the first episode of his podcast, The Monthly, Mike Meginnis observes that the chapbook, as a form, appears to be something “people enjoy publishing much more than they enjoy reading.” This struck me as a smart, if generalized, reflection on the medium. Like new literary magazines, a spattering of chapbook publishers appears to sprout from nowhere every few days. This is likely an outcome of the current economic and cultural climate, where it is too expensive for upstart presses to print full-length books when more and more readers gravitate towards digital editions or free online content. The chapbook offers a cost-effective way to put something physical in a reader’s hands, but the ease of production also lends the form to hurried publication and incohesive collections.

Yet when a publisher puts real time and consideration into a chapbook, when a writer tells vibrant stories that bleed into the margins, and when a sharp design meets fitting, fascinating artwork, the result is too great to ignore. In other words, the result is Families Among Us, winner of the 2013 Black Lawrence Press Chapbook Competition. Continue reading

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)