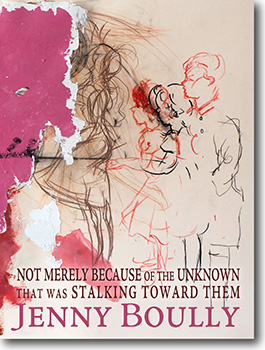

84pgs/$14

Tarpaulin Sky, 2011

In this prose-poem hybrid, the texts of Peter Pan have been enmeshed, re-corded, and spun into a thickness of sensual detail and slippery cross-reference. Under Boully’s fingertips, Neverland has burst open like a sodden swollen root, spilling out cutlery, birds, bearskins, thimbles, peas, open windows, mermaid scales, pubic hair, damp pirate beards, and fairy dust, of course. It is up to the reader to square their pith hat and push on through the glorious mire.

And mire is the word I’d use, not unkindly. NMBUSTT is loud and querulous, muddles about with the borderlines between childhood and adulthood, and reaches across the porousness of growing, to prod about with the solidified state of being grown

As to plot? The text does not so much progress as struggle, deliberately, through cycles of decay and death, memory, forgetfulness, love and the rejection of human love. Already I am exhausted, and I have told you hardly a fragment of it.  Eighty-four pages (of which, sixty-five are the text), and it feels like so much more.

This is in part because Boully’s Neverland, her claiming of this imaginative space, must jostle with countless other Neverlands. While reading, I was drawn into thoughts of: Peter Pan, the play of which I haven’t seen since I was a child; of the ballet version, all lithe flying fairies veiled in silence; of Hook,  where Tinkerbell is a sassy, shrunken Julia Roberts and Pan is a bewildered, then gurning, Robin Williams; the tear-stained, summer-garden story Finding Neverland; black Leather Jacket-clad Kiefer Sutherland in The Lost Boys; Michael Jackson and his lost boys; and after a search on Tumblr, a photoshopped imaged of Disney’s smirking Peter Pan with full sleeve tattoos and  an ear gauge.

Boully herself informs us in the acknowledgments page that the italicized parts within her text are directly lifted from Barrie’s Peter and Wendy and Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. In addition, certain incidents in her work were inspired by Andrew Birkin’s J.M. Barrie & The Lost Boys: The Love Story That Gave Birth to Peter Pan. The result is so many threads, suckered tentacles, oblique roots, that reading is an act of willpower, rather than of flow.

Here, stop here. Let’s take a look at Boully’s creation, what she has staked out in terms of imaginative space. She has divided each page into two halves, the above ground and the below, bisected by a thin line. The lower half of the page forms a constant footnote, is given its own title, ‘The Home Underground’ The upper half, though it might be expected to take precedence, is equal and parallel to the lower half. Both sections focusing primarily on Wendy’s experience of the writhing, multiple Neverland:

These things may fit inside a thimble: a pinch of salt, a few drops of water, the tip of a woman’s ring finger. I will give you a thimble, says Wendy. I will give you a thimble so that you will know the weight of my heart. A thimble may protect against pricks, pin pricks, needle pricks, Tinkerpricks, but not hooks, never hooks. When he stabs his hook into you, you will see that his eyes are the blue of forget-me-nots – but that is Hook and not Peter – Peter who will forget you, whose eyes are the color of vague memories, the color not of the sky, but rather of the semblance of sky, the color of brittle-mindedness, of corpse dressings, of forgetting.

This is from the upper part, towards the opening of the book, although where it appears does not seem important. Time is muddy and unstable in this imaginary world. In the above passage there is much appearance of action and argument, guessing and second guessing, though little can be pinned. Identity blurs. Is it Peter or Hook who is stabbing ‘you’ – and who are you? Are you Wendy? I thought Wendy was speaking? A lost boy? Speakers speak beside one another, over the top of one another the way children and angry lovers do. Threats are made, implied, and off stage (because the text is a kind of stage) threats are carried out, children led astray, and little mossy graves appear, as if imagined into being.

Every now and then a tinny thud when an Americanism slips into the vocabulary of an English-Neverlandish child. Examples of diaper, jelly, and ‘done grown’ rattling uneasily against the terribly English ‘shan’t’ and ‘ever-so’. In Boully’s Neverland there are Katydids and Whippoorwills and cobs of corn, strongly indicative of an American landscape. But then the island, Barrie’s creation and others, has always been a place of mingling worlds, the real, the impossible, whatever a child may make a reality of. Yet sometimes it feels in the linguistic tics that Boully is trying to put on a play-accent, simple rhymes and all, and sometimes slipping. Is this muddling intentional? There are, after all, tiny Tinkerbell-sized tampons. What purpose do the intrusions of the modern or the American serve? This is a questioning text, and asking questions of it feels imperative.

Still, being quite a passive reader, I found myself enjoying the lower space, ‘The Home Underground’, sections more. Not least for the apt position they take up, under the open world, liminal, both physically and psychically. The way the mood is reflective, sometimes maudlin, such as in this passage, taken from a little further on in the book:

Wendy knew, all along, that she would die. She had a song for it. Sing us the kind of afterlife that you would like to have, oh, Wendy. And Wendy sings. She sings the kind of afterlife that she would like to have, and in her afterlife there is her little house, and Peter and she are married- but not like before, but more real, in a marriage made more real, which meant that Peter, little bird, someday too would need someone to help him half way to a place hidden between two stars.

For these sections alone I would carry this book with me, though I might only rarely crack it open. The book requiring the energy of the precocious child I never was, my inner worlds never as slimy and rich as the intentional chaos of this particular Neverland.

Helen McClory was raised in both rural and urban Scotland. She has lived in Sydney and New York City and is currently to be found in the Old Town of Edinburgh in a three hundred year old flat opposite a tunnel into the underworld. The manuscript of her first novel KILEA won the Unbound Press Best Novel Award 2011, and publication is currently being sought for it. To keep the wire steady, Helen is working on a second novel about the intersections of love, failure and technology set in New York, New Mexico and Cornwall. Progress on this at Schietree

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)