158 pages, $15.95

Review by Anna Mebel

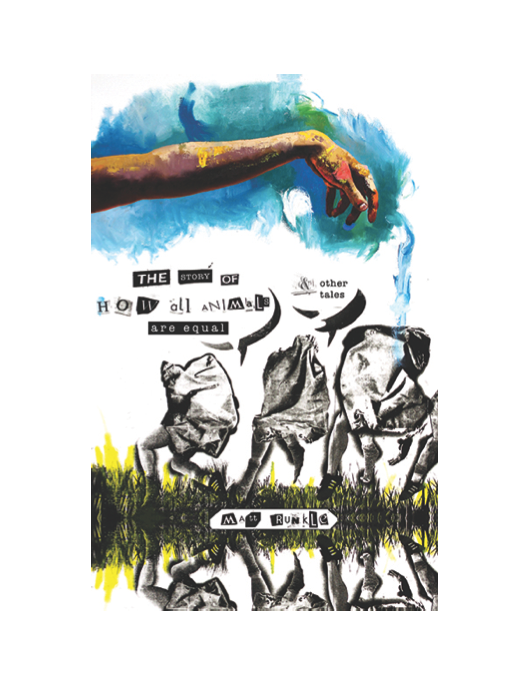

Matt Runkle is both a writer and a visual artist currently studying at University of Iowa’s Center for the Book. He writes short stories and prose poems, makes collages, comics, and art books. Though The Story of How All Animals Are Different & Other Tales is his first book of short stories, Matt Runkle has also published a zine called RUNX TALES. As an artist, he is interested in assemblages, juxtapositions, things that most people would discard. These artistic practices filter into his writing. In The Story of How All Animals Are Different & Other Tales, Runkle mixes fairy tales, love stories, satire, dystopia, prose poems, and careful observations of the ordinary.

The stories are often very short but always efficient, showing us flashes of worlds similar to our own, yet slightly off—an apocalyptic scenario in which people live out of their cars, a supermarket located on the border between two countries, a town in which the punishment is election to public office. He finds “places where comings and goings occur from every side,” where borders dissolve and relationships become unstable, letting worrisome aspects of human nature emerge.

The title story of the collection, “The Story of How All Animals Are Equal,” is about the friendship of a straight woman and a gay man. They call their sleeping arrangement asexual, aromantic. The coinage “aromantic” feels like a close cousin to aromatic, capturing the sweetness of a relationship never touched by sexual desire. Their friendship and sleeping arrangement work only briefly, because, ultimately, the two are a mismatch. Runkle finds the tragedy and beauty in such mismatches—he treats relationships as collage.

The stories in the collection are driven by unfulfilled desire and the weight of unexplained, mysterious pasts. In “Spiel,” we are placed in a gift shop that sells the blandest of gifts, but in a few brief sentences we learn about the speaker’s partner, who would be able to make any of the store’s merchandise seem exciting and new, if she was actually there, working in the store. In “Warmth,” the two main protagonists part tragically because one has suffered longer than the other although the reader never learns how exactly. Some characters, like Carl of “Veterans Day,” try to escape their pasts by making up a glamorous story, but their lies quickly catch up to them.

Successful short-shorts either work by the power of suggestion, letting the reader imagine a bigger world beyond the frame of the narrative, or they’re just plain fun—a good joke that doesn’t outlast its welcome. Still, I’m with Donald Barthelme in that the “aim of literature is the creation of a strange object covered with fur which breaks your heart.” Some of the shorter stories in the collection felt slight, caught up in tricks of language. But while Runkle had many stories with beautiful sentences, the stories I enjoyed most were ones that broke my heart, that showed me something about the strangeness of being human.

***

Anna Mebel lives in Syracuse, New York. Her writing has appeared in Broke Journal, Tin House’s Open Bar, and is forthcoming in 90s Meg Ryan.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)