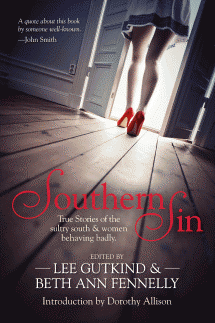

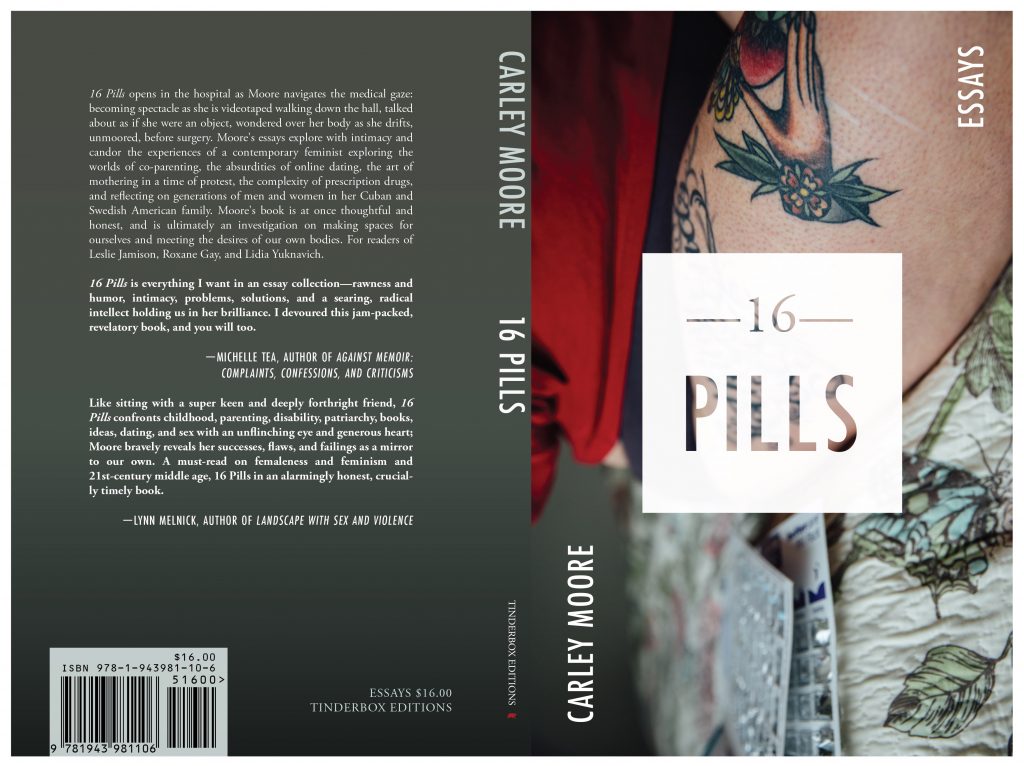

Tinderbox Editions, 2018

REVIEWED BY JESSICA MANNION

__

Carley Moore’s debut collection of essays, 16 Pills, is a therapeutic read, and while no book can boast being a panacea for the ills of modern life, this one comes close. Moore writes like her life depends on it. She dissects the stories of her life with intelligence and precision, and invites the reader to share in her examination. Feminist, political, funny, and irreverent, Moore’s essays are masterful, and show a true love of the form; the stories are deeply personal, while still tapping into shared human experience.

Moore is a Professor of Writing and Culture at NYU, and an Associate for Bard College’s Institute for Writing and Thinking. She is a poet, a novelist, and an essayist, and her love for writing in all forms is clearly evident in this collection. The essays range from short, sharply focused vignettes revolving around a single memory or issue, to more broadly universal themes, drawing copiously from her life and her reading for inspiration. She selects passages from a wide scope of material, using quotes from Zadie Smith as well as more surprising sources, like an article about lice from Scientific American.

The title 16 Pills refers to the number of essays in the collection, and themes of illness, physical and mental health recur throughout. These are not the only themes Moore explores, but the early years of her life had a huge impact on her, and the far reach of this time is evident.

The collection’s first essay, “The Sick Book,” introduces the basis of these themes of body and wellness. As a child, Moore was hospitalized for an unknown medical condition that caused her muscles to contract and twist to the extent that she sometimes couldn’t even walk. While doctors struggled to diagnose her mysterious illness, she was helpless to control her own body, not just the muscle cramps, but her daily schedule, and the tests she had to endure. What she could control were her observations, her thoughts, and her memories. “The Sick Book” is doled out in a series of brief vignettes, memories from this frightening time. Her eventual diagnosis is revealed – although not in this essay – and she refers frequently back to this time as she explores its repercussions on herself and her family.

Moore has a neurological condition called Dopa Responsive Dystonia. She shares this hereditary disease with her father, although hers is a much more severe case; her father’s lived experience with the disease was mild enough that he didn’t even know he had it until his daughter’s diagnosis. The essay “On Spectacle and Silence” begins with a brief anecdote from this time – a memory of she and her father sitting together on a green recliner. From here she launches into an exploration of personal responsibility, political activism, and what it takes to become an adept witness and advocate, as well as the amount of work it takes to learn to play ones role in all three. She judges the failings of herself and her father in particular here, and explores the role of media and storytelling in guiding self-reflection and as a vector for personal and political change.

Moore seems to delight in combining the sacred and the profane: “Nitpicking and Co-Parenting” starts as a humorous essay about she and her ex husband dealing with their 5 year old daughter’s bout with lice. The essay discusses the challenges of co-parenting and raising a well-adjusted child, then veers into a feminist examination of the practical work of nitpicking (i.e. it’s a very women-dominated profession), the trope of a nitpicking wife, and then ties that to the film “Alien,” wherein Sigourney Weaver’s character Ripley, is the hero – but a female hero who is ultimately performing another kind of nitpicking. Ripley does the tough job that no one else wants. She cries and she is in pain, but she knows what she must do and simply does it. Moore explains how “[Ripley] embodies a feminist ethos I’ve come closer to realizing as a single, co-parenting mom” (19).

In the essay “My Pills,” Moore explores the essay as an agent of healing, albeit a difficult one. “Isn’t the essay form itself an anti-palliative, a recipe for pain, and an invitation to cause trouble?” she asks, “Because the writing of an essay is the untangling of the worst kind of mental knot” (86). Moore warns that the essay isn’t a cure-all, and the process not simple. Such examinations can be very messy, but they are also necessary. “In my essays, I plan to wallow and wander, to get stuck and linger over painful moments and difficult texts. I am trying to figure something out here and to name it for myself and for you my dear friend” (86). A better metaphor for an essay in Moore’s hands might be something more akin to the irrigation of a wound. Moore is not afraid to bare it all, to show her vulnerability, as messy as it can be. Instead she probes the things that most people shy away from, and the result is healing.

16 Pills doesn’t offer easy answers, instead it invites the reader to become comfortable with uncertainty. As she says in “Resistance Dance,” “… I feel ‘mixed’ about a lot of shit. If you give me a problem, I will feel two to ten ways about it. I speak from multiple positions. [… ] The essay is my most comfortable genre because it allows me to honestly change my mind. I like landscapes that feel like mixed tapes and I’ll take a queer dance floor over a straight one” (146).

Although she delves into some dark places, Moore’s 16 Pills is ultimately a journey toward optimism and hope, a journey toward self-discovery and acceptance. If only we all could cast light into the dark corners of ourselves with such alacrity.

__

Jessica Mannion is a writer living in Brooklyn, New York. She writes essays, articles, poetry and short stories. Her writing can be seen in publications including Crixeo, and Alliterati, among others. She has a BA in English Literature from the University of Alaska, Anchorage.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)

![Timid Son FINAL.doc [Read-Only] [Compatibility Mode] - Word 6152015 113804 AM](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Timid-Son-FINAL.doc-Read-Only-Compatibility-Mode-Word-6152015-113804-AM-192x300.jpg)