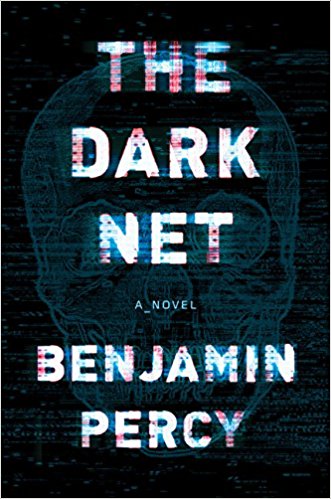

(Cinestate, 2017)

(Cinestate, 2017)

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL NATALIE

—

As befits a gory dissection of horror films, Michael J. Seidlinger’s My Pet Serial Killer opens cinematically.

Lights up on an ennui-stricken graduate student. We’re given a few cryptic words—Claire, student, master—and an impressionistic portrait, its features subordinated to a pervasive sense of unhappiness. Over the next thirty pages, this misery takes shape: What begins as dissatisfaction becomes misanthropy, what begins as loneliness becomes a profuse yearning. An attending psychologist would revise his diagnosis from depression to narcissism; a malignant strain of narcissism with a litany of other issues percolating underneath—but leaving the patient somewhat anchored in reality.

Through Claire’s perspective, we are given the terms of a conversation we can’t yet understand: “I,” “you,” “woman,” “man,” “master,” “pet,” “fight” and—crucially—mystery. Twenty-odd pages in, another character takes shape: Victor Hent, the Gentleman Killer. We’ve seen Victor before, in prior literary and film incarnations. His dark, slicked-backed hair and the shallow world into which he wades evoke Patrick Bateman—particularly as portrayed by Christian Bale.

Predictably, Victor and Claire forge an instant attraction. A reader scouting for tropes might read Victor as Claire’s karma; the runoff of her own toxic psychology into the real world, here to punish her for her narcissistic power fantasies—fatally so. One might expect Claire to join the ignominious ranks of the foolish dead, the slasher victims who could’ve averted their sad fates simply by locking their front doors.

Nope. Seidlinger bucks our first expectation by quickly and firmly establishing Claire as the dominant half of the pair.

But it’s not just that Claire dominates Victor: Her power fantasies are so fully actualized it quickly becomes difficult to picture her suffering any kind of comeuppance, even at the end of the story.

What follows My Pet Serial Killer’s cryptic (but suitably disturbing) opening scenes is a gory romp which explores not only the psychology of murder and murderers, but also the psychology of horror films and audiences; a the literary answer to the burgeoning film canon of self-referential horror flicks: Funny Games, Behind the Mask: the Rise of Leslie Vernon, Cabin in the Woods, and so on.

Without giving too much away—in fact, we can file this comment under ‘Captain Obvious’—Claire’s attraction to Victor stems from his capacity to kill. He kills, she watches. More critically, Claire applies her forensics expertise in order to enable and preserve her clumsy, impulsive “pet.” She’s not just complicit; she’s in charge, and the manner of her voyeurism implicates the audience in her mindset.

Specifically, she tends to watch the murders as a filmgoer would—through camera. Seidlinger makes the deft decision to incorporate old-school cassette tapes here, recalling the early days of slasher flicks. Furthermore, Claire demands Victor cultivate a certain aesthetic, ramp up his Patrick Bateman flair—to her, this isn’t just murder; it’s art, and it doesn’t count if it fails to project an aura of mystery.

At his most direct, Seidlinger cuts the narrative with italicized reflections, which he maddeningly labels “optional.” To oversimplify: These reflections raise Claire’s voice up to the level of the author’s, with deranged allusions to the novel’s critical underpinnings. In these rants, Claire frequently imagines how her work would play with audiences. If Seidlinger’s “optional” tag regarding these italicized rants reflects a genuine ambivalence—as opposed to just a tongue-in-cheek sense of humor—that’s understandable. The old maxim goes “show, don’t tell.” However, it’s My Pet Serial Killer’s direct and deeply interior moments that transform the novel from a violent, audience-shaming slog into a visceral think piece.

For example, the first of the italicized segments contains a satirical advertisement for the horror genre, a darkly hilarious rant which blends Claire’s fetishes together with the fascinations of the audience. Crucially, Claire’s ramblings inch close enough to sanity that the reader can—in some sense—“get” her. From this union between Claire and the audience springs one of the novel’s principal obsessions: mystery.

“In ‘Nothing Ever Happens,’ you live a life of certainties until you come across a mystery, and whatever you do to make sense of that mystery only ever feeds that mystery…in “Nothing Ever Happens,” the mystery is really the only reason to live…with such a state of mind, it’s a good enough reason to let deviance be our director.”

Implicit in this fascination with ‘mystery’ is the admission that the horror genre is popular, not because we enjoy pain, but rather because we hate boredom—and mystery rescues us form that boredom. Horror’s guided by the same core motive force as any other genre; the impulse towards escapism. The fact that the novel admits this early on salvages it from potential silliness—the ridiculousness inherent in a comparison between the average reader and the deranged Claire.

But as the novel unfolds and Claire’s actions become increasingly brutal, the distinction between hating boredom and enjoying pain becomes murkier. Seidlinger’s attempts to incriminate the audience become more potent. And here lays the novel’s true monster: Not Victor or even Claire, but the sense their macabre performance exists because only because we want it to.

In other words, the novel’s real horror is the fear that attends guilt.

And it works.

Seidlinger achieves this black, guilty fear through many channels—not least, a provocative narrator and the bare, brutal facts of the plot. But Seidlinger’s most subtle success lies in his novel’s structure; a well-made two-room insane asylum to house the narrative’s philosophically-demented screams.

My Pet Serial Killer has two parts: Be Mine and You’re Mine. The aesthetics of Be Mine concentrate mostly on blood, Dexter style. You’re Mine is more honest about what happens when people die—all those other, somehow less sanitary, fluids. Both stories have an interplay of sex and violence, but the sex becomes more prevalent in the latter half. While both arcs have a docudrama element, Be Mine plays out many of the classic slasher film tropes, while You’re Mine is heavier on snuff and found footage elements. Furthermore, Claire’s reflections on the genre change in emphasis—from the film to the television format. This seemingly inconsequential shift actually belies an important theme of the novel: That the violence never stops.

In other words, while the novel is never a comfortable read, it gets progressively less so. We graduate from the familiar horror tropes and their attendant fantasies, moving into cruel and uncharted waters. All the while, from beginning to end, Claire mocks—or, more precisely, sarcastically applauds—the reader for staying with her on her journey even as it rockets beyond sterile, commercially-accepted fantasies towards something far worse. In the end, you’re left wondering if you’ve crossed a line—Claire’s line.

The line between hating boredom and enjoying pain.

It’s no mystery—My Pet Serial Killer wants us to feel complicit in Claire’s crimes.

And we always are, even more than we would be than if we were watching them in filmed form. After all, it’s a novel. Our own imaginations are doing the work of conjuring everything that happens. And there lies the story’s principal strength: In the manner of a true nightmare, doubts and fears linger on. Even now, as I slowly reaffirm the difference between the audience and the monster.

—

After its original release by Enigmatic Ink in 2013, My Pet Serial Killer has been re-published by Cinestate today, Halloween 2017.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)