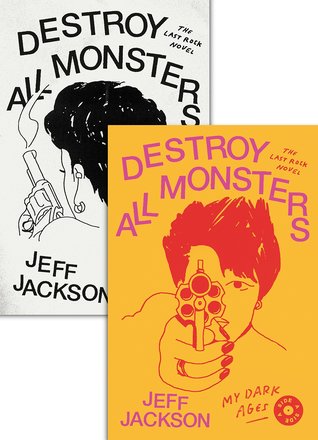

(FSG Originals, 2018)

REVIEW BY MICHAEL J. SOLENDER

__

Rock “n” Roll’s primal appeal has always been its siren call as a refuge, a way of life, and state of being for the disaffected.

Rock has time and again used its power to transport alienated youth to realms without parents, teachers, fast-food bosses, and authority types.

Even in rock’s infancy when the doo-wop vocal group Danny & The Juniors first recorded “Rock ‘n’ Roll is Here to Stay” in 1958, lyricist David White proclaimed rock would “never die.” While it’s unlikely White envisioned rock’s evolution and subcategorization into psychedelic, folk, surf, heavy metal, grunge and garage rock, he instinctively knew the transformative power of this music prophesizing, “Rock ‘n Roll will always be our ticket to the end.”

The end is where Jeff Jackson’s new novel, Destroy All Monsters, The Last Rock Novel, begins. Jackson’s tome explores the troubling consequences when something we love too much betrays us.

A spontaneous epidemic of violent shootings is happening at underground rock clubs across the country. Musicians are being shot and brutally murdered while performing – yet the music continues.

Each new horrifying shooting builds upon the last. Their impact is felt and experienced in total, both repellant and attractive to those caught up in the scene.

Jackson journeys into the violence through the lens of a small handful of 20-somethings who aren’t sure where their life is headed and face each day unconcerned about existential questions any greater than which band is playing where and when. The carnage is seen strangely as matter-of-fact, a not-so-unexpected byproduct of the dreary world they inhabit, outcasts by their own design.

Xenie, Jackson’s heroine and primary vehicle, is a tense and pouty goth-girl who is a club regular following the likes of the Carmelite Rifles at the Echo Echo (inspired by Jackson’s hometown-Charlotte Milestone Club). Florian and Shaun, aspiring songwriters, rocker wannabes, and probably good kids growing up who mowed the lawn without being asked, are in Xenie’s orbit as is Eddie, a hanger-on-er, perched just on the peripheral of the in-group, desperate to connect with them for validation of his self-worth.

Theirs is a world of garage bands, sold out concerts, and mealy clubs with questionable acoustics. Heroes for these kids aren’t wrapped in the flag, found hawking sneakers, or making their class honor roll. They’re windmill-swinging armed guitarists with vintage amps serving up numbing balm to soothe past indignities and inoculation against the uncertainties of what’s next.

The successive club killings aren’t portrayed as crimes as much as inevitable occurrences, each compounding upon the last and slowly gaining momentum. Early on Xenie senses connectivity in the killings and muses over her relationship to them.

Bands were being shot in the middle of their performances all across the country. The noise duo at the loft party in the Pacific Northwest. The garage rockers at the tavern in the New England suburbs. The jam band at the auditorium on the edge of the midwestern prairie. The bluegrass revivalists at the coffeehouse in the Deep South. The killers simply walked into the clubs, took out their weapons, and started firing.

Everybody was slow to call it an epidemic They didn’t want to believe these deaths were connected. I tried to discuss it with my coworkers at the diner, but they reacted with raised eyebrows and sideways stares, treating me like the customer who only orders glasses of chocolate milk and claimed the birds were trying to communicate with him.

I kept my ideas to myself, even though it was clear the killers weren’t acting in isolation. It was as if they’d all been infected by the same idea. They seemed to be following the same subconscious marching orders.

Somehow, I knew each act of violence was a prelude to another. The night before each new shooting, I’d find myself closing the curtains throughout the house and pacing figure eights in the bedroom carpet without understanding why. These events seemed like something plucked from my most disturbing daydreams.

Jackson takes his reader into the club scene of his fictional blue-collar Arcadia, an any-town USA burgh where home base for his crew of clubbers is far from chamber of commerce write-ups or upscale millennial haunts serving $19 martinis.

So strongly do some followers identify with certain bands, they transcend mere groupie status and become communities complete with the viscerally connected and those on the outside looking in. History is filled with these swooning masses: Elvis, the British Invasion, the Grateful Dead’s Deadheads, Phish Phans, all enjoyed such super-fans.

Members of this clique nervously pluck out their eyelashes, wear strategically ripped jeans, and spend their paychecks on scalped concert tickets. Xenie and Shaun share matching scars on their wrists, twinned memories of the recent past where the goal was not hurting themselves but FEELING something, feeling ANYTHING. They belong to the only group that will have them – each other.

Being an outsider is not the exclusive realm of contrarians as anyone who has ever longed to be a cool kid can attest. Destroy All Monsters taps into this fundamental aspect of the human experience, nonbelonging, illustrating how those on the fringe coalesce forming tribes just as difficult to crack and complex as the mainstream groups they are eschewed from.

The book is presented in a unique “A” side “B” side format that mimics that of an old-fashioned 45 rpm single requiring the book to be turned and flipped in order to be read. Just like the two-sided vinyl short plays, each side, “My Dark Ages’” and “Kill City” can be read in either order and stand alone.

Side A, the lengthier “track” offers a more linear story line and heavier scene development. Destroy All Monsters B side is almost like a background vocal track, with details and context to the murders acting like harmonies to share underpinnings and give depth.

With the meatier narrative, Jackson asks his readers to more fully ponder the “whys” in the storyline and see how it frames up against America’s political impotence and vexing inability to actionably respond to our own chronic violence and never-ending mass shootings.

Jackson paints in sepia tones, his words create a filmy, nicotine-stained haze giving rise to a discordant lifestyle born from the ability to alienate and repel external understanding.

Staccato bursts and short-sentences create tension bordering on anxiety, tapping to the core of these characters’ angst, stripping it bare. Jackson artfully eliminates distance between action and the reader, hijacking with a propulsive style into real-time dilemmas of belonging, assimilation, acceptance, and attachment.

Our protagonists’ fatalism in the face of epic violence is no more startling than America’s benign acceptance of real-consequence school shootings and daily gun violence. The stark difference however between Jackson’s fictional characters and everyday Americans is in their not waiting for someone else to “do something,” but in acting on their own morals and values in real-time response.

Florian’s face is twisted into an odd strangulated shape. He has a simian brow, but his minuscule eyes simmer with intelligence. His large expressive mouth seems to conceal a perpetual secret. Essential components of his onstage charisma. His band has been invited to headline a gig at the Echo Echo, a local club shuttered since the shooting. It’s a special concert to try to resuscitate the Arcadia music scene. An opportunity to pay a worthy and genuine tribute to Shaun. If it only didn’t mean placing himself in the line of fire. Soon the other members of Florian’s band will arrive, and they’ll have to make a decision. As he navigates the empty hallways to their rehearsal room, he listens to the lonely echo of his footsteps. The crumpled paper in his hand begins to itch.

Destroy All Monsters effectively reveals the dichotomy of loving and hating something simultaneously, a space where what was once embraced and slavishly followed, ultimately becomes reviled, a demon to be exorcised.

__

Michael J. Solender lives and writes in Charlotte, N.C. Follow him on Twitter @mjsolender.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)

Two Dollar Radio’s latest publication is hot off the press. Found Audio by N.J. Campbell is a Russian nesting doll of a novel with layers of mystery, mythology, madness, and suspense.

Two Dollar Radio’s latest publication is hot off the press. Found Audio by N.J. Campbell is a Russian nesting doll of a novel with layers of mystery, mythology, madness, and suspense. If you grew up in the rural South, you’ve probably heard tales of big cats, vampires, the Bell Witch, flesh-eating kudzu, and other terrors that go bump in the night. You may have even encountered some yourself, though probably not all in a single outing. Unfortunately for the protagonist of The Vine That Ate the South––and fortunately for us––he did.

If you grew up in the rural South, you’ve probably heard tales of big cats, vampires, the Bell Witch, flesh-eating kudzu, and other terrors that go bump in the night. You may have even encountered some yourself, though probably not all in a single outing. Unfortunately for the protagonist of The Vine That Ate the South––and fortunately for us––he did.