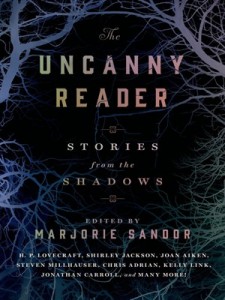

St Martin’s Griffin

576 pages, $21.99

Review by Dan Bradley

The hardest readers to shock and surprise are, perversely, voracious consumers and lovers of horror; we’ve read it all before. So with this new collection of 31 uncanny tales, refreshingly attentive to international and contemporary voices, can editor Marjorie Sandor revamp the strangeness and power of the uncanny for a new generation of readers?

The collection is inspired by the ‘haunted word’ itself. Sandor introduces the collection by tracking the etymology and semantic shadows cast by ‘uncanny’ and how its broad insinuations snake through languages and cultures, touching upon so many parts of our lives, enabling it to inspire such a wide ranging collection of tales ‘from the darkly obsessive to the subversively political, from the ghostly to the satirical.’ In Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay ‘Das Unheimlich’, commonly translated as ‘The Uncanny’, his catalogue of experiences capable of creating an uncanny sensation, which ‘speak to the uninvited exposure of something so long repressed… that we hardly recognize it as ours,’ could easily read as a template for the greatest horror art, fiction and cinema of the past century:

When something that should have remained hidden has come out in the open.

When we feel uncertainty as to whether we have encountered a human or an automaton.

When the inanimate appears animate. Or when something animate appears inanimate.

When we see someone who looks like us—that is, our double.

The fear of being buried alive.

When we feel as if there is a foreign body inside our own. When we become foreign to ourselves.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)