INTERVIEW BY MANDY SHUNNARAH

–

To say Hanif Abdurraqib writes about the music that’s the soundtrack to our lives is an understatement.

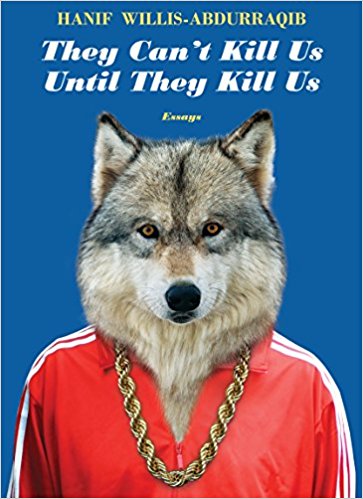

They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us is the first essay collection from Abdurraqib, who is a music columnist at MTV News and a poet whose work includes the collection The Crown Ain’t Worth Much from Button Poetry. Whether it’s Marvin Gaye, My Chemical Romance, Chance the Rapper, Carly Rae Jepsen or Nina Simone, Abdurraqib is writing about the music that makes sense of the world and validates the experiences of those who suffer most when the world is doling out its pain.

The essays in They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us are a forthright look at life at the intersection of music, race, class, and culture. A Springsteen concert opens the door to a meditation on Michael Brown. Putting Nina Simone vinyls on the record player gives way to a discussion on how black people’s stories are taken from them by white hands. Listening to My Chemical Romance’s The Black Parade on the tenth anniversary of its release leads to a discussion on death, grief, and hope in the dark. Future’s recent albums ask listeners to consider the kind of breakup-induced heartache from which it feels impossible to fully heal. A look back on years of Fall Out Boy shows stirs a contemplation on friendship, suicide, and living on your own terms. A ScHoolboy Q show explains how a word can be violence on one tongue and deep companionship on another, depending on the color of the mouth that said it. A Cute is What We Aim For show ponders misogyny and the feeling of having grown up when the art you once loved hopelessly stagnated.

These are not essays on background music or classical tunes praised in the ivory tower of academia. Abdurraqib writes on a breadth of musical taste that is wide and varied, yet all of it is accessible and modern––likely artists Millennials grew up listening to or currently have on their iTunes playlist. Abdurraqib is taking the music many already enjoy and asking us to consider its more profound implications. Readers are asked to investigate the ways in which music shapes and informs our lives.

This essay collection is not for white readers in the sense that it doesn’t pander to them. There are essays on experiences that white people will never know firsthand––like the terror of being pulled over by police because you supposedly look like a criminal or the sanctuary of black churches. For white people, the essays are a necessary trojan horse: it sells them what they want––music writing––but it gives them what they need––social justice.

I talked to Hanif about writing, music, and black joy.

Mandy Shunnarah: What I love about your essays is that they live at the intersection of the personal, the political, and the musical. It’s clear the essays span over the course of several years, so I’m curious what the trajectory of your writing was like. Did you start out writing music essays and incorporate your story and issues of social justice over time? Or have you always blended the three?

Hanif Abdurraqib: I think I’ve always been interested in how the personal can work its way into a narrative without (hopefully) overtaking a narrative. I say personal and don’t simply mean the actual body––but also the emotions, interests, feelings that rest in the interior of the personal. I’m not really setting out to get people to believe what I believe. Rather, I’m trying to get them to find something new and unique in music. Perhaps risk seeing it as something greater and seeing where their own personal narratives might align within the songs they love. So I guess I’ve always blended the three, but I’ve never really imagined it as blending as much as I’ve imagined it as a different way of viewing a landscape I love looking out onto.

MS: Your taste in music is eclectic and it’s clear your ear is keener than the casual listener. How did you become interested in a wide range of artists? Are there genres you feel like you’re only just dipping your toes into?

HA: I grew up in a house with a lot of music, and so I kind of developed my ways of hearing and listening at an early age. It’s a bit of a stretch to say that I grew up in a “musical family”––it’s not like my siblings and I were in a band––but my father played instruments around the house. I had a brief and unsuccessful stint as a trumpet player.

But more than that, I listened to music that my parents carried with them into the house. Jazz and soul and salsa and funk and songs from South Africa. I am the youngest of four, so I got to absorb all of the music which trickled down from my older siblings. My older brother and sister would introduce hip hop to our house, sure. But also, since we were children of the 90s, I got exposed to grunge, metal, and classic rock––all of which allowed me a path backwards, so that when I was old enough to start charting my own musical tastes, I was doing it with a working knowledge of the past, and I’m always so eager to dig out the tasty and unique parts of history resting underneath a recording.

I want to know about what happened to Fleetwood Mac in between Rumours and Tusk. I want to know about Nick Drake’s brilliant burst of output and then his mental and emotional decline. I watch The Last Waltz once every single year and mostly just for the way the camera picks up Mavis Staples whispering “beautiful….” after the Staple Singers join The Band for a stirring rendition of “The Weight.” I see a whole story in all of those moments. I’m listening to the actual music, sure. But I’m also interested in filling the spaces that simply listening sometimes doesn’t afford a listener.

When I was a kid, my brother and I used to sit in our room with a tape-recorder boombox, and we’d listen to the radio all day long, back when folks had to listen to the radio all day to maybe catch a song they loved once or so every six hours. And when the song we wanted to hear came on, we’d rush to press record on our tape recorder, and rip it right off of the radio. And there was that burst of excitement––hearing this thing you’d been hoping to hear and rushing to capture it. It felt like the slow opening of a gift that ended up being exactly what you wanted, every single time. I’m trying to capture and maintain that kind of excitement about music. I’m trying to carry that with me, even when I have the weight of so many other things to compete with.

MS: Out of the hundreds (thousands?) of concerts you’ve been to, if you could only pick one to see again, which one would it be and why?

HA: Oh, I think probably one of the early Fall Out Boy shows that I write about in the essay “Fall Out Boy Forever” in the book. Likely the 2003 Halloween show they did in Chicago at some shitty venue where the stage collapsed.

It was such a fascinating moment because I don’t think I’ve ever had a moment like that again, where I’m watching the turning point for a band happen in real time. My pals and I had been going to their shows since about a year earlier, when they started playing to tiny crowds and were getting heckled endlessly. The Chicago emo/pop-punk scene was at an interesting place in 2002-2003, because a lot of these dudes were just coming out of MUCH more hardcore bands, and the transitions for some of them proved to be difficult. Fall Out Boy was kind of a band without a country, largely due to Patrick Stump’s distinct singing. They were too pop for the hardcore scene, but definitely too difficult to access for the pop scene. It took about a year for them to get traction, but when they did, they really took off.

That Halloween show was the one that really turned the corner for them. I remember it well because shit got so crazy that the stage collapsed and they had to stop playing. Pete Wentz was used to wading out into the crowd and getting this mostly lukewarm reception, but that night when he walked out into the crowd, kids were jumping on his back, tearing at his shirt, grabbing his head. It was wild. There were almost 100 kids packed into a room that maybe only should’ve held 70, tops. You could see on the band’s faces that they had no idea what was happening. In a way, Fall Out Boy was born that night. Since I’m pretty disconnected from the band in its current state, I’d love to see that one more time.

MS: Some of the most poignant essays were those talking about the myriad ways joy is ripped from black people by white people and the systems of oppression they created. In addition to celebrating black musicians, which you did beautifully in They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, what are some of your favorite expressions of black joy?

HA: The way my friends sing the words to the songs they know and then make up the rest. The opening moments of a spades game––that first hand, when anything feels possible. The old black woman at the eastside market I go to from time to time who looks me up and down and says it’s good to see you, baby, and I know she means it. The way a joke can echo through a group text and shrink distance. The grease that lingers on the hand and then perhaps upon the fabric of pants after dipping fingers into the Popeyes box. The way the clock pushes past midnight on a Tuesday and I look at my watch in a city that is not my own and insist that I have to go to sleep, and the people I love will give me a hard time until I am leaning over, wrecked by laughter, no longer tired.

I don’t know. I think in order to talk about the lack of joy as a type of violence, you have to know the architecture of joy itself, and realize how precious it is when it is in arm’s reach. I think you have to accept the many forms it takes. These days, I’m interested in the joys that are pre-existing, already waiting for me to slide into. I’m trying to remember those best and not take them for granted.

MS: Since your last book was a collection of poetry, I’m curious about how you balance your poetry and your essay writing.

HA: I imagine everything as a poem, some blooming wider than others.

__

Mandy Shunnarah is a writer based in Columbus, Ohio, though Birmingham, Alabama, will always have her heart. Her creative nonfiction essays and book reviews have appeared in The Citron Review, The Missing Slate, Entropy Magazine, New Southerner Magazine, and Deep South Magazine. You can read more on her website, OffTheBeatenShelf.com.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)

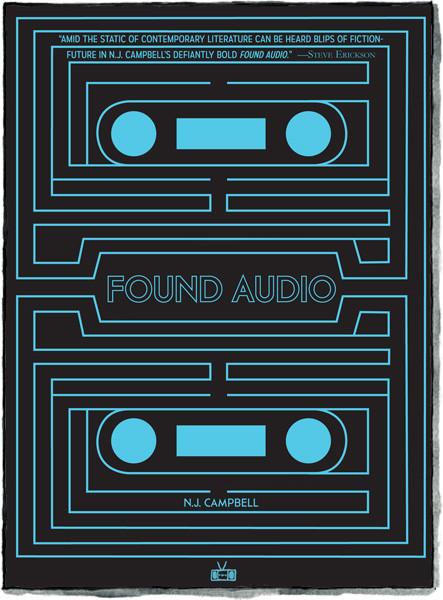

Two Dollar Radio’s latest publication is hot off the press. Found Audio by N.J. Campbell is a Russian nesting doll of a novel with layers of mystery, mythology, madness, and suspense.

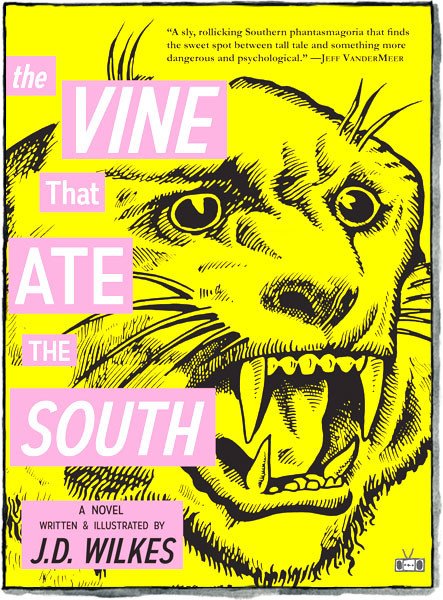

Two Dollar Radio’s latest publication is hot off the press. Found Audio by N.J. Campbell is a Russian nesting doll of a novel with layers of mystery, mythology, madness, and suspense. If you grew up in the rural South, you’ve probably heard tales of big cats, vampires, the Bell Witch, flesh-eating kudzu, and other terrors that go bump in the night. You may have even encountered some yourself, though probably not all in a single outing. Unfortunately for the protagonist of The Vine That Ate the South––and fortunately for us––he did.

If you grew up in the rural South, you’ve probably heard tales of big cats, vampires, the Bell Witch, flesh-eating kudzu, and other terrors that go bump in the night. You may have even encountered some yourself, though probably not all in a single outing. Unfortunately for the protagonist of The Vine That Ate the South––and fortunately for us––he did.