[wpaudio url=”/audio/7_3/Stalcup.mp3″ text=”listen to this story” dl=”0″]

Priscilla led Isaac by the hand outside, walked him to a tree, placed his back against the trunk. She pulled an apple from between her breasts and placed it on his head. She told him to stand perfectly still. Priscilla strode twenty paces away, turned, notched an arrow into her bow, pulled it back with muscular yet trim arms-at that point Isaac fell in love-and let it fly: the apple impaled, the arrow quivering in the bark. Isaac stepped from underneath, left the apple thrumming above. They both could imagine a crowd roaring.

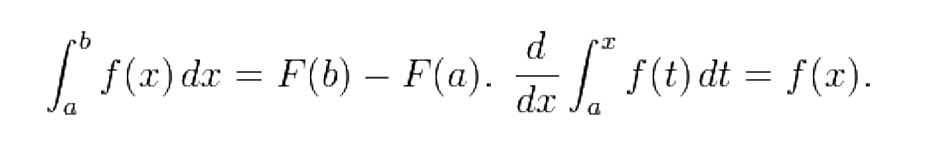

Priscilla had found Isaac in a bar drawing strange symbols onto cloth napkins:

He wrote the words limit, bubonic, infinitesimal, infinite.

Isaac had left Cambridge because skeletons in rags on slow-moving carts were about to bring the plague. He walked home to Lincolnshire, and before kissing his mother’s cheek he went to the pub in the town square. When Priscilla said hello he looked up at her, wrote f(x) = x2, f'(x) = 2x. He said, “The slope of f(x) at x = 3 is 6.” He wrote f(x) = x2, F(x) = 1/3x3. He said, “F(x) at x = 3 is 9. F(x) at x =2 is 8/3. So the area under f(x) above the x axis from 2 to 3 is 19/3.”

“Do you see the pattern?” he asked her. “Do you see the beautiful pattern?”

“Yes,” she said. “I do.” She took his quill and drew the graph, perfectly. He’d never seen anyone but men do that.

Isaac said to Priscilla, “These are the things I know to be true: Geometry is the study of shape, calculus the study of change. White light is the combination of all the colors of the rainbow. Every object persists in its state of rest or uniform motion in a straight line unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed upon it. Force is equal to the change in momentum per change in time. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.”

She leaned forward and kissed him.

Priscilla said she was an archer, needed a partner for her circus act. She downed the rest of Isaac’s beer, plucked a coin from her boot and left it on the table. He picked it up, bit it, said, “I believe counterfeiters should be hanged.” She then led him outside and showed him what she could do and he was astounded. She said she needed more practice before the audition; they had ten days, so Isaac took Priscilla to his ancestral home. She slept in the library, on a velvet couch, surrounded by gyroscopes and globes and prisms and models of the planets with the sun in the center and a telescope made from mirrors. Isaac visited her there each evening. During the days they practiced against the plum trees, persimmon trees, and cherry trees of the family orchard, but it was always an apple that Priscilla plucked from her breasts.

For nine days Priscilla got it right nine times out of ten. On the tenth day Priscilla got it right ten times in a row, and they knew they were ready. They walked to the field bordered by forest that the circus transformed into a festival for four days every four years. When they arrived, men on stilts were erecting the tent. Isaac peeked under the flap to see a pyramid of clowns lifting the poles that would support all that striped fabric. The fat lady was eating five apple pies. The bearded lady was shaving her legs using a bucket and a straight razor. A man with his legs crossed walked by on his hands. A child stood on the tip of an elephant’s trunk, spinning a ball on her finger. Acrobats practiced on the fences edging the field, leaping and flipping and landing in the same place. A woman with a python and her hair as her only clothing blew fire. The manager trotted up, his muscular, unclothed torso turning to furred horseflesh, hooves.

“What can you contribute to the Wriggling Smothers Bar None Circus?”

Priscilla answered, “Death-defying acts.”

They led the centaur to the boundary of the prairie, to where the forest of apple trees began.

Isaac stood dutifully underneath a tree, his spine aligned with the trunk. Priscilla-in her silk striped dress sewn just for the occasion, pinned and tucked to show her lovely legs clad in thigh-high striped stockings, garter straps disappearing under the folds of her skirt-took aim. Her triceps were as taut and curved as bones, her bones underneath were strong enough to support all that tension, and Isaac clutched his side, amazed and pained that his rib could be so improved by being out of his body. The arrow flew, the tip pierced the apple, the sound of contact reverberated through every trunk in the forest, Isaac stepped from underneath, grinning, and thousands of apples, enough for barrels of cider, hundreds of pies, fell from the tree, pounding Isaac’s head and shoulders, thudding down his back, burying his feet. He got so many thumps he slumped.

Pricilla explained to the manager that the trees at Isaac’s home weren’t as laden, where they practiced the trees weren’t wild and flush-a cascade wasn’t part of the act, but could he see the one apple still held aloft by the arrow, the feathers still shuddering, could he see the one that didn’t fall, the one her arrow held? While Priscilla tried to secure them a spot in the traveling circus so that they could see India and Ireland and Jamaica and Africa and the Americas, while Priscilla prattled, Isaac dreamt.

Tuning forks chimed; snakes swallowed apples whole, mounds traveling along the pipes of their bodies; Isaac felt rain, saw a rainbow; a snake in a tree told him, “You, you can understand.”

While Isaac watched, God reached into the dirt at his feet, formed animals from soil. Then God spit, and shaped a man. God pulled a woman from the side of the sculpture. She ate a pomegranate, and she didn’t want it undone. She fed seeds to the man, and they didn’t plummet. The woman said to Isaac, “The universe can and must be understood by active reason. It is never wrong to know-there will always be mysteries.”

The snake dropped to the ground. Night fell. Falling apples glinted silver in the moonlight.

Birds were replaced by bats. Their wings resisted the pull downwards; an arrow pierced a bat and it fell. The force extends to them. How high?

The moon arced across the sky, slashed by each branch it passed.

In his dreaming slumber, Isaac thought, Apples drawn to the center of the earth. The moon-what makes things fall makes planets orbit. Makes tides. Why women taste like the sea. The same force draws the earth up to the apple, the earth up toward the moon. Attractions across empty space.

Isaac awoke, his head aching and bandaged. He’d been placed in a bed, a cot for Priscilla near him on the floor.

The centaur said, “Congratulations. You have a job.”

Priscilla said, “Together, we will see the world. We will be daring.” Moonlight shone through a window, the reflected sunlight making Priscilla’s skin luminous.

Isaac spoke, “I’ve been shown. Gravitas. We fall to the earth in supplication, bound to the clay we were shaped from. The earth is the greatest thing, but every thing moves us-the nearer you come, the more I want to fly in your direction. Each of us is drawn towards each object in the universe. Feeling this lure-instead of just the pull to fall-that is the highest form of praise.”

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)