~by Kate Schapira

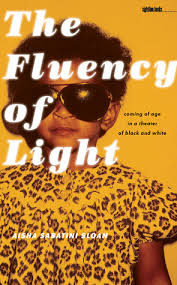

Sightline Books: The Iowa Series in Literary Nonfiction

128 pgs/$17.95

Discussions of whiteness and blackness in America all too often devolve into a series of platitudes. In fear, fury, insistence or exhaustion, statements grow more and more categorical; poetry, complexity, and improvisation leak out. Aisha Sabatini Sloan’s collection of essays—facets of memoir gathered around, crystalized and refracted by works of art and bodies of music—works to put them back.

Sabatini Sloan orders one of her most intense and far-ranging essays, “Silencing Cassandra,” around riots in London when a police officer killed a young man named Mark Duggan. She quotes a BBC interview with a black Londoner named Darcus Howe, who says of his grandson, “’I asked him the other day, apropos of the sense that something was seriously wrong in this country. I said, “How many times have the police touched you?” He said, “Papa, I can’t count, there have been so many times.”’Inaudible remarks continue.” What sound can include both the inability to speak and the refusal to listen?

Sabatini Sloan turns to P.J. Harvey’s howl of an album Let England Shake, Anne Carson’s essay “The Gender of Sound” and playwright Joseph Chaikin to show these riots not just in the context of their history but by the light of works that “[let], like a needle in the vein, the blood out of a sick body, extracting a kind of poison”; that make, according to an unnamed Jamaican musician she quotes, “a sufferer’s sound.” “Silencing Cassandra” also draws glints from Revenge of the Nerds II, the Skatalites, Scared Straight, Secrets and Lies, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Malcom Gladwell, Graceland, Parenthood, and dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson; photographers Lorna Simpson, Charlie Philips and Arnet Francis; writers on music David Katz and Les Black. Writing, in a book about race, of a riot with origins in racism is not unusual or unfraught; what has power is that Sabatini Sloan shows how this is not news, how these works throw off reflections, half-tones, shudders, resemblances we could see if we were watching, hear if we were listening.

In the same essay, Sabatini Sloan writes,

… What haunts me is that I could see that my student was right, that

we were living in a massive delusion, where people seemed literally to be wearing

costumes and stage makeup. But I couldn’t do anything to comfort him about it. I

didn’t know how to tell him that it was possible to see the illusion without feeling

warped by it. To play your role in the game while fully accepting that it was fake,

without feeling like you were going to lose your mind.

The experience of art is one thing that’s kept Sabatini Sloan from losing her mind, which is not to say that it provides a comfort, a refuge or an answer. Another thing that seems to have helped is love. Many essays in the collection are more intimate: with anger and image, music and grief, they mediate the smaller but similarly absorbing complexities of family. In “Resolution in Bearing,” scenes from Claire Denis’s 35 Shots of Rum, Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas, and her father’s home videos cast their lights and shadows on how isolation, independence and a sense of loss tinged the author’s teenage summer with him in Paris.The story of her Italian grandfather, who disowned her mother—not, as our lazy minds might expect, for dating a black man, but simply for moving out to live with friends—is contrasted with Jungle Fever, counterpointed with Fellini’s filmography and interlaced with other stories of her mother’s family and her grandfather’s country to show how history remains in the bodies we feed, displace, injure, embrace.

In other essays, conceptual artist Adrian Piper and painter/performance artist Ana Mendieta offer widely different ways to grapple with fears, presumptions, and cultural noise about which bodies belong where, which bodies are safe or unsafe. “Cicatrization,” focuses on Mendieta’s work as a companion to the author’s trip to South Africa; Sabatini Sloan—who describes herself in the book’s first essay as “brown and curly”—admits, “I noticed myself thinking: so long as there are white people around, we are safe. At which point I knew that I was facing things within myself I hadn’t had to see before. Africa was going to be my reckoning. With what I still can’t name.”

Once again, there’s a whiff of unease about this choice of focus and direction—an American goes to a “Third World” country and realizes something? C’mon! But namelessness breaks the epiphany narrative, easy resolution leaking out the cracks. Mendieta’s work re-enacts and ritualizes“the invocation of violence through burning and blood … the fracturing that history has imposed upon flesh—the pain that either moved our ancestors to this country in the first place, or that which ruptured their bodies in transit.” It releases “shakes and screaming,” it “turns prose into gibberish.” It cuts the story open. Some art does name, but art in all its forms offers us—like the notes “you know [Thelonious Monk]’s not playing” in the book’s first essay, “Birth of the Cool”—the option to return to without naming, to feel what runs under and around the flat statement and the designation.

And so the essay I returned to was “Fawlanionese,” although when I first read it I thought, “This isn’t coming together.” The title is the author’s mishearing of “Fall on your knees” in the carol “O Holy Night.” Mishearing, misunderstanding, selfishness, illness, and stress; economic segregation, environmental injustice, systematic incarceration; the “something fragile” that composes walls, floor, the ceiling that falls in chunks while the author and her father await her mother’s arrival; the flickerings of gentleness and love. I want to press my eye, my ear, to the pieces that don’t unify or homogenize but do call to each other, to the leak where things can leave or enter.

***

Kate Schapira is the author of four books of poetry, most recently The Soft Place (Horse Less Press). Her eighth chapbook, The Ground / The Pass / The Wave, is coming out this summer from Grey Book Press. She lives in Providence, where she teaches writing at Brown University and elsewhere, and organizes the Publicly Complex Reading Series.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)