Editorial Assistant Erinn Batykefer sat down with [PANK] Author and Contest Judge Trace DePass to discuss Trace’s incredible work what he’s looking for in a winning manuscript!

Editorial Assistant Erinn Batykefer sat down with [PANK] Author and Contest Judge Trace DePass to discuss Trace’s incredible work what he’s looking for in a winning manuscript!

From the poem “The Tesseract Tethers Rooms”

i tire of death, relative to me, not passing, in 3D. i need this divorce.

you go writ(h)e,

go anthropomorphize rot incessant all thru my body. look! there’s ceiling to this

passivity: dirt. here’s this room i’ve named —

me.

outside that room lives just my other room,

another empty tomb, maybe

a separate cube,

which, after peering at it for long enough, i too

on some days become. watch: i’ve lost

track of my own tesseract face

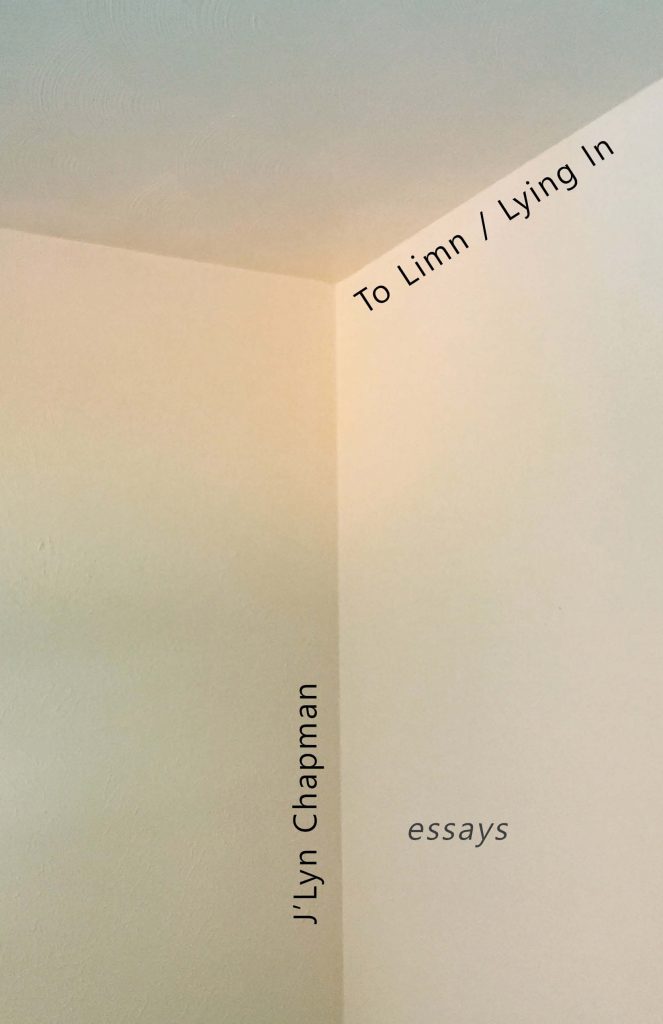

Buy Trace’s Book Here!

Erinn Batykefer: You’ve edited and juried several awards and anthologies, especially for works created by younger writers. What excites you most when you’re wading through the slush pile for those contests?

Trace DePass: I get the chance to witness the heart & mind of a young person at work. Hundreds, if not thousands of them, at the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards, for instance. I watch how the world turns. There are usually always gems to find. For Scholastic’s “Best Teen Writing of 2017” I was really trying to amplify works that changed me if not perhaps the institutions these kids walk into, or see, daily—there was this essay, “On Ableism” which centers the voice of disabled & differently-abled bodies in intersectional justice & climate activism, which eventually led me to the work I do know (in 2019) with the Climate Museum. It mentions the cold war term “sacrifice zones” as lands designated for oblivion in case of nuclear fallout & disabled people as the “quintessential sacrifice people.” So much work by young people gets lost, whereas it could completely change discourse if we were to give it the space to do so. It’s exciting to be able to teach or reference the published work of young people to other young people. I feel like I’m doing participatory action research by spreading THEIR participatory action research & stories, curating an ongoing literary conversation in the culture of children (even if only for as long as I can hold that attention).

EB: What excites you about judging this contest for [PANK]?

TD: I enjoy reading poems in the conversations or arcs that the author curates for them. PANK will always get works that are experimental, whimsical, or playful. I’m glad to be a part of this kind of world-building. It’s probably going to be pretty intense so that’s exciting, lol.

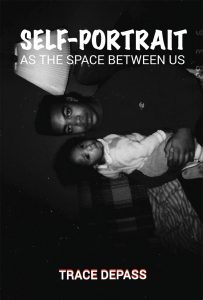

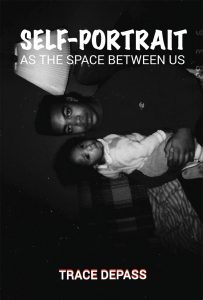

EB: Your own Big Book, Self-Portrait as the Space between Us came out in 2018 from [PANK]Books, a collection that seeks to place a reader “befuddled in what befuddles me.” The poems here resist drawing neat conclusions and instead embrace nuance and contradiction. Is that the point of poetry?

TD: Nuance is one of the drives of my poems. I can’t speak for all poet motivations. I like acknowledging we don’t only live in 3 dimensions; once you pick up an object & literally move it you’re witnessing 4 dimensions (not including the sensory or psychic), then shifting to love or death or my father, a National Guard veteran who also created presets for Korg & Yamaha pianos from scratch. I think English can be confusing & often misinterpreted or sometimes collapsed or sullied by interpretation. There are poems that are nuanced to speak aloud & bring into conversation, even if the voice in our head doesn’t hear that on the first read of the work. I’m not trying to necessarily be undeniable. I’m trying to delineate or make non-linear & up to interpretation through image & sound up until I’m not. Then, the questions: is about consent? Is this consent? How many childhoods, generations, stories, layers, and things like entry points are here? Life doesn’t resolve itself in a simple, mathematical answer & you can say that is a poem, perhaps not all poems.

EB: What are you hoping to see in the submissions for this contest? What, in your opinion, should a book of poems do?

TD: I don’t have an absolute—probably not even a firm—stance on what exactly books of poems “should” do as an experimental, often described as musical + narrative + lyrical, poet. I believe there’s a stance taken for an author in how they want to be read or taught. I think a book of poems considers a lot of people & gives context, subtext, meta-text to those people. It’s completely up to the discernment of the author on how to tether or go about that. The book should have wants, drives, reckoning, character, among other things maybe. The poems will do what they want or need to do if you allow them to direct you. I hope to see what that looks like.

EB: One of the most striking iterative images in Self-Portrait is that of the speaker as Darwin’s Finch, scrabbling and transforming and evolving in his understanding of an absent father and his own identity. You’re also creating a fellowship program with the Climate Museum for high school students. Is science a triggering town for your creative work?

TD: The bird comes as goes like my father has for his own reasons. Some years I knew neither of my parents. Other years, I’m just like them. I see a lot of my own blackness in the migration of birds, yes. Leaving & loving for me are nuanced things.

I’ve worked with a climate scientist that has told me that there’s subjectivity & intention also behind science. I believe there is a nature to the questions we pose, experiment to answer, & thus a human behind the veil of “objectivity.” My book definitely dabbles with this idea. Given there is no absolute objectivity, what isn’t a little triggering sometimes? I question the nature of my own birth so I think I’m pretty strong-willed.

The kids as well as the staff I work with at the Climate Museum open me up to the idea of care & warmth in science, as much as scientific suggestion in the poems. One of our kids, Ota, has a poem that questions if love has a place in a world where we neglected it, this environmental predicament & man-made problem. I love that poem. All the poems in our program, Climate Speaks, feel nuanced in a similar. If you’re in NYC on the evening of June 14th, come check us out at the Apollo.

EB: If you could encourage the writers who will be submitting their books to [PANK] for this contest to keep one thing in mind, what would it be?

TD: You’re not completely alone. Give it time. Give ALL of it time. Play with the script everyday. Keep editing. Don’t just edit for a prize. It doesn’t stop here. You will have to live with what you write & the context that brings you to the page. They are not exclusive. Don’t be afraid to play with form. You may be an entirely different person at the end of editing, likely after publishing it, & so on. Feel everything you feel. You have the initial & final say. Put the poems in conversation in real life & see how you feel. Learn from the process. Think of how you want you & this book to be taught. Get to know some of the author’s work at [PANK] & beyond! Being an author, especially of a book of poems, will not make you rich & it takes a lot of life for poems to make you any kind of wealthy.

EB: Anything else you’d like to share with [PANK]? [PANK] loves you.

TD: If you’re looking for a reader, teaching artist, drummer, beatboxer, playwright, or poet for the summertime, I’m available!!!

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)