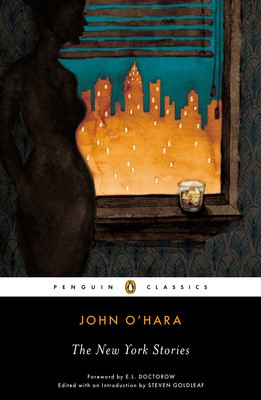

Penguin Classics

400 pages, $17

Review by Bess Winter

John O’ Hara is considered the father of the “New Yorker story,” a term thrown around in M.F.A. workshops as shorthand for conservative, formally traditional, and WASPy. The New York Stories, a new edition of 30+ of O’Hara’s collected works published between the 1930s and early 1970s, is a study of class, ambition, and the extinct publishing landscape that took O’Hara in and fostered him.

O’Hara won a National Book Award (for Ten North Frederick, which was adapted into a film starring Gary Cooper), and was the author of BUtterfield 8, whose film adaptation earned Elizabeth Taylor her first Oscar, and whose title is the namesake for a slew of coffee shops and vintage stores nationwide. From the 1920s through the 1970s, he shaped the urban American short story landscape and, by extension, the mid-century American aesthetic (think highballs, Cary Grant, The Oak Room), by manufacturing hundreds of stories. With the publication of The New York Stories (and new editions of a clutch of O’Hara’s novels with introductions by Lorin Stein and others), Penguin attempts to wedge O’Hara, who—despite his many successes—has always been more of a writer’s writer than a literary great, somewhere in between Hemingway and Fitzgerald.

In the collection’s foreword, E.L. Doctorow paints a picture of a writer who, lacking a college education and “connections,” worked his way to the top of a mainstream literary landscape that still rewarded the tenacious outsider. Maybe this explains the gin-soaked bitterness of O’Hara’s work. As Doctorow points out, even late in his career, O’Hara felt everyone was against him. Doctorow wants us to read O’Hara through a biographical lens, and it’s difficult not to; O’Hara was a writer who worked hard at the business of writing. This comes through not only in the sheer volume of writing he produced over the course of his lifetime—here are over 30 stories set in Manhattan alone—but in his stories’ preoccupation with work and success. Stories in this collection are about the precariousness of the publishing industry, floundering Broadway actors, aging film stars, female advertising executives struggling to deal with men (Judith Huffacker, the protagonist in “The Nothing Machine,” is ancestor to Mad Men’s Peggy Olson), cafeteria workers who stash money under their floorboards, and projectors of dirty films.

Being invited to read O’Hara biographically, though one of the most interesting aspects of this new collection, raises issues not only for the book, itself, but about O’Hara as an author. Editor Steven Goldleaf is faithful to O’Hara’s method of organization; the stories are arranged alphabetically, by title, according to the author’s belief that every story he wrote was equally strong. The author was wrong. The best unfold into a complex revelation of character and situation that confound our expectations of the traditional short story. “Call Me, Call Me” and “A Phase of Life” are stunners, reversing our impressions of the stories’ protagonists in the boldest and most masterful way I’ve ever seen. The opening of “We’re Friends Again,” the only novella in the book, is as affecting as any passage from Dickens. But the worst are just confounding. All of this is to say that quantity, in O’Hara’s case, does not equal quality. Even Harold Ross, the New Yorker’s first editor, vowed never again to “purchase an O’Hara story he couldn’t understand.”

Then there’s the matter of privilege. It’s hard not to see O’Hara as an embittered member of the establishment, and to read his stories through this lens. He lacked a college education because he couldn’t afford to go to Yale, the only school he wanted to attend. He wrote to live—but he earned his bread and butter from the preeminent American literary magazine, and published there more than any of his contemporaries. Despite his talent for writing characters from every social class, he secured his place among the literary elite early in his career, and stayed there until his death. O’Hara wanted only the best and, most of the time, he got it. If he wasn’t born into privilege, he was savvy enough to know how to secure it.

The New York Stories, in its unevenness, gives us an in-depth picture of O’Hara: his style, his foibles, his talent and shortcomings. Whether it’ll serve to wedge him between Hemingway and Fitzgerald, however, is another thing. Hemingway and Fitzgerald have pretty broad shoulders.

***

Bess Winter’s short fiction has been awarded a Pushcart Prize and appears recently, or is forthcoming, in Indiana Review, Wigleaf, Carousel, A Strange Object’s Covered With Fur, and W.W. Norton’s Flash Fiction International. She is a Canadian-American living in Cincinnati.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)