Interview by Emily Coon

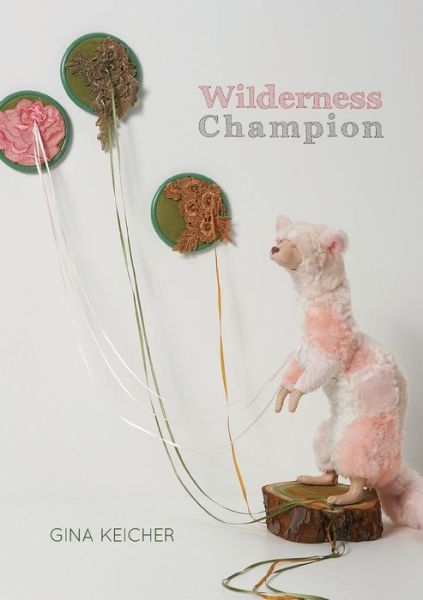

Consider the strangeness and dysphoria of modern existence in America. Poet Gina Keicher does in Wilderness Champion, which roams highways, explores curiosity cabinets, guards lawn volcanoes, and dances in a gun store after the apocalypse.

Emily Coon: Many – most – of the poems in this book are organized into paragraphs rather than lines. Some paragraphs include lines of dialogue. Can you tell me more about that choice?

Gina Keicher: At some point in revision, each of the prose poems saw line breaks. At some point, I also tried to offset the dialogue and give it more space on the page, but the momentum felt disrupted to me. If I write in lines, I tend not to give dialogue its own space, so when I transition to prose poems, I let that convention slide. The dreamy, fluid roll from prose to dialogue appeals to me.

Also, embedding the dialogue became a way to make turns on a technical level. In Wilderness Champion, things change, appear, and disappear. Things get weird. So, letting someone talk seemed like a strange crafty move instead of a strange subject maneuver.

EC: In the book, you have a series of Introductions poems. While they have the names of sciences (e.g. Introductions to Teratology), they orbit largely inside entertainment spaces like circus sideshows or pool halls. What can we learn about science from entertainment? And why many Introductions to a subject, instead of one?

GK: These are sharp questions, Emily. I’m still trying to wrap my head around the relationship between science and entertainment and their ongoing conversation. Science is entertaining—Meerkat Manor, science museums, setting our alarms to a werewolf hour so we may witness a comet for two seconds. Entertainment is scientific. Television shows are written to commercial cuts and time slots. Horror movie scores are set to make us jump. Strip club stage walls are often lined with mirrors. A carnival doesn’t just have rollercoasters, it has rollercoasters and carousels and fun houses and tame, tiny train sets. All these coincidences and choices point to some kind of science, an effort to maximize a spectacle’s entertaining potential for an audience.

Science and entertainment are both necessary, and can also be so fundamentally devastating, to life. Science can (attempt to) tell us the truth, but entertainment tells us, “It’s going to be okay.” Things get a little scary when that reassurance becomes an explanation for how the world functions. I’m fascinated by the ways humans have tried to explain how the world works throughout history. Mythology, science, entertainment. I get pretty wrecked trying to think how humans will explain entertainment someday.

The pluralized Introductions qualify the moments—numerous turns and unfoldings—that inform our understanding of an experience. We don’t go see a sideshow, walk through, and leave. There are exhibits that compel us to stop and reflect, exhibits we ignore, exhibits we photograph. Human experience is a prism. To acknowledge each refracted element gives a fuller appreciation of its depth.

EC: Many of the poems in this book involve what seem to be reactions to the fundamental strangeness of modern American existence. For example, genuflecting in the grocery store in “Introductions to Asphalt” and serving novelty cereal to the dead in “The Family Eulogist Called in Sick”. What is the cause of these reactions? Where is the most immediate place to find dissonance within our lives?

GK: Modern American existence is strange (and also really sad) to me. Maybe these big, weird gestures are attempts, perhaps overcompensations, to react to human experience in a culture in which reactions seem so two-dimensional. Everything is on a screen. So, all the tangible and strange things throughout the poems in Wilderness Champion feel like things to touch and see, things that call for a physical reaction. That being said, that’s a reflective post-writing-the-book answer.

When I was writing these individual poems, the relationships we have with the world around us, our family, friends, loves, and selves—and sometimes the lack of relationships with these people—felt like the large-looming filter for these poems. Family trouble, relationship strife, distant friends, discomfort with the self. It’s really hard to be a good, and content, human when trying to sort these things out and trying to figure out how we relate to the world in our strange new bodies and skins. Lungs turn into anvils. Ghost fathers of dads not-yet-dead populate their living rooms. Shipwrecked lovers build a new boat every day to watch a storm destroy the hull. So, circumstance and connectivity inform a lot of the strife for the people in these poems.

EC: How does dream-logic relate to poem-logic?

GK: When I had my wisdom teeth extracted, the last thing I remember before going to sleep was the oral surgeon telling me to “pick a dream.” (There was probably a flickering moment of anxiety during which I worried I would pick the wrong dream.) And then I woke up with a mouth full of blood and cotton falling out of my cheeks. I didn’t remember any of my dreams and I sure don’t think I had the opportunity to choose them.

We don’t get to pick our dreams (unless we learn lucid dreaming) and I have yet to be okay with a poem whose logic I handpicked. If I know how to write a poem, I’m going to be bored writing it. Dreams and poems have their own lives and agendas that are separate from the dreamer and poet. While our personal experiences, desires, fears, and anxieties may manifest themselves in dreams and poetry, there’s a similarly uncontrollable quality in dreaming and poetry. Dreams and poems are imperfectly engineered swells that we piece together in waking life and revision, that we make sense of and imbue with meaning. Sometimes we skip that last part and I think that’s cool. Sometimes we just say, “I had a dream about a walrus eating a grilled cheese sandwich and that’s all.” Both possibilities interest me and keep me excited about writing (and dreaming).

EC: “The General” spans ten pages. In the poem, people in a town search for a nameless general in a huge carnival attraction. The searchers are bugged in their homes and given instruction such as “how to kiss right”. This poem reminded me a lot of “Escape from Spiderhead”, the George Saunders short story. Are we looking at the past, or the future, or something else entirely?

GK: “The General” was a deviation for me and it was fun to try a longer poem. I took a class at Syracuse in which we read Frank Stanford’s (amazing) epic poem The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You, which has nothing to do with battle, but one thing I admire a great deal in that poem is the endless permission Stanford gave himself to get strange, to run with ideas and language, and when he got stuck to just go somewhere else—back to characters we had already met or back to a drive-in theater or an outhouse or a farm or a dream.

“The General” felt like my opportunity to give myself some permission to stretch and I’m still not sure why. I started with the idea of the speaker, a partner, and a town worshipping or seeking the general—this unidentified (and unidentifiable) revered being. From there, I think I ran to the idea of holding fast to loved ones while simultaneously looking for death because that’s where we’re all headed. The idea of the carnival and entertainment—the conventional, the cheesy, and the morbid. The idea of war disrupting the domestic even after the fighting is over. It was a lot to throw in the air, but I wanted to riff off the images, sounds, and ideas and see what happened. Tense-wise, I imagined it in terms of the present, but if it’s the future I wouldn’t be surprised.

EC: Human relationships to animals appear in several poems. Notably, in “Jangles the La Mancha Goat”, the narrator envisions dressing her pet goat in a jacket. What do you think of animals wearing clothes, and of designerwear available for sale at pet retailers?

GK: I was talking about this with my cat and we agree that animal fashion is weird and kind of adorable. It’s kind of like the video of a hamster eating a tiny burrito. A tiny burrito is totally not nutritious for a hamster and yet I can’t stop looking. My cat is requesting a hoodie with PANK embroidered on the back. Do pet retailers sell those?

EC: Why did you take the title of the last poem in the book, “Wilderness Champion”, for the book’s title?

GK: At one point in Werner Herzog’s documentary Grizzly Man, Timothy Treadwell films a fox bounding through a field. The camera is all shaky and Timothy keeps saying, “Go, go on home.” After a minute or so of bounding, the fox slows down and Timothy says, “Hey there, little champion” and this stuck with me in a weird and sad way. The book was originally named for the first section—Familiar Animal Engines—those practical things we see or experience, but the name for those things sounds weird. I wrote the poem “Wilderness Champion” when I was working at a grocery store. During each shift, I saw such a large number of people that by the end of those nights I wanted zero human contact, just wanted to fold into myself and reflect. So, the poem was this anti-toned pastoral to a nature that I didn’t really have the time or energy to appreciate. As I revised the manuscript and looked at its shape, I saw a longer narrative emerge—this strange landscape where the self, family, and relationships exist on an off-kilter terrain. The “Introductions” poems feed into the title as well. People learn and survive. Maybe they even win at life.

EC: You’re the curator of the Party Fawn music-and-reading series in Ithaca, N.Y. A plastic party fawn presides over readers and listeners alike. What is the Party Fawn? What’s the relationship between music and live poetry (if any)?

GK: The Party Fawn includes a few writers reading fiction or poetry—work that generally makes people want to party—followed by a performance from a local Ithaca band, which also makes people want to party. Who doesn’t love a baby animal in a party hat?

As for following the readings with a musical set, when I think about how long writers can toil over language, rhythm, lines, and sentence—and how long musicians can toil over the music and the words—it makes an awesome and weird kind of sense to let the two arts join forces at a party that celebrates both.

***

Emily Coon is a writer whose work has recently appeared on the Ploughshares blog and at #MIXITUPFEST in Sweden. She studied literature and cognitive science at Cornell. Connect with her on Twitter at https://twitter.com/emily_coon_.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)