Dear Reader, If you’re a bastard, send me a letter. If your father was absent from your life, please do write. If you haven’t talked to your father in years and don’t know if you will– because he’s a bastard—an epistle of any style is welcome. Use words or visuals, no limit. I’m collecting letters from individuals who have been affected by the absence of their fathers for dear Gerald, an epistolary project I have been working on for the past two years.

We all seem to suffer fatherlessness, be it a particular father loss, through degrees of unavailability, estrangement, abandonment or death, and since we all are offspring of capitalist patriarchal societies, I find this to be interesting.

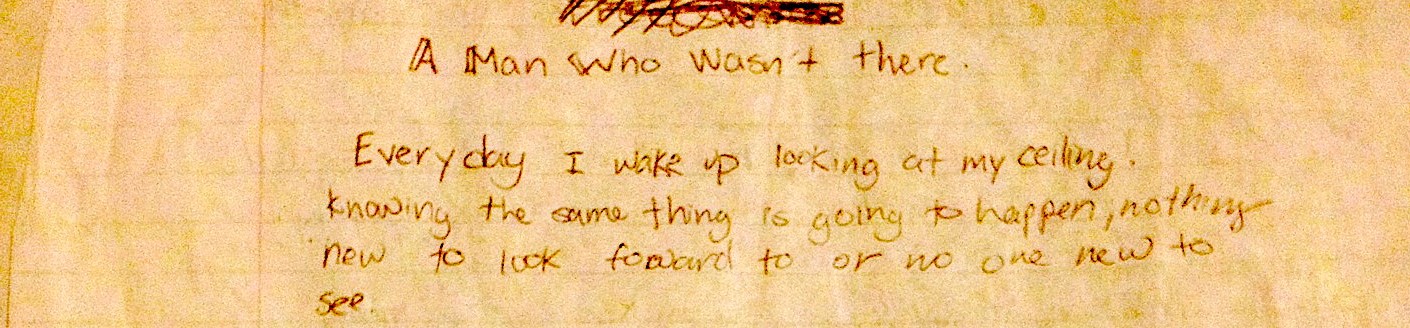

dear Gerald, a collection of epistolary poems, which came to be because my mom asked me if I wanted to write my father in Guyana. It was my 33rd birthday. Last time I saw my father, I was 3 years old. Some years later, I’m not sure when, he was deported back to his homeland, never to return to the States. Because I wasn’t sure what to say, I wrote poems instead.

dear Gerald,

I broke away

from murmuration and murder,

do you stand in the crowd?There must be a theater where you show,

a marquee with your billing.

Selective and unapologetic,

you’ve wandered shore to shore.England doesn’t ask you

where you’ve been,

doesn’t tumble from your neglect.No, she will not cry,

not puzzle over your roll.No cry Brooklyn, Georgetown.

No tear London, Kingston.

Tobago, Chicago—not even.But into our brothers’ arms,

we supine and cry.

The poems inspired a project idea: Self-publish the collection to exchange for letters from people who are estranged from their fathers. The letters will be used for a second collection, which I’m considering titling Who’s Your Daddy? And lastly, go to Guyana and give my father a copy of dear Gerald. The project has been funded by the Center for Cultural Innovation in California. dear Gerald, like most of my writing, attempts to uncover, reclaim, and restore, which means that I’m often writing from a place of loss.

Dear Dad,

Now at 31, for my sanity, my heart, my soul- daddy I need you to understand that I don’t blame you. You need to understand that no matter what anyone said, you were always my father and I love you, now forever and always. I want you to know that I pray for you every night. My greatest fear is that primo will call and my next visit with you will be the one where I, as your oldest child, will have to make your final arrangements.

I moved to Oakland seven years ago, and the Bay Area lost a lot of folks to the Jonestown Massacre, which happened in 1978, in Guyana. This is how most people know of the country. Kool-Aid was never the same after I learned that detailed associated with my father’s birthplace. For several years, I strung together a series of facts or stories or yarns about him, constructing a man of my mythical imagination. Through this creative act, I was asking: who is my father? Who is the man who taught my 19-year old mom to drive with his Cadillac? Whose ancestors were from a marooned colony in Venezuela? Whose police officer father was found drowned? I wanted to give him a location in my life, a kind of hereness that allows me to put myself at the center of the narrative and deepen my understanding of who I am.

Dear Tennyson,

Then there’s this father thing: thorny, complicated, despairing. Without you, my persona was blurred; for what did I have to wrap around me, but a tatterdemalion of indifference and lost empowerment? If fathers are crucial to our confidence in navigating the world, then what of me? Through much of my life, you hardly knew me: my talents, my friends and concerns; my loneliness and how I could remain stubbornly stone-faced. Did this bother you? Did I matter?

We are always in this active state of answering who we are—the process may be one of shedding or accumulation, invention or dissimilitude, whatever is your flavor, we seek ourselves in any shape or form. However the answer guides us, we come into a new meaning of ourselves. As I explore different modalities for healing, especially now living in the Bay, I’m always confronted with the question of how do I show up. When I introspect on that, I turn to my parents: how did my mother show up? How did my father? Discussing the dear Gerald project with others, the pattern of absentee fathers became uncomfortable and disturbingly apparent—a patriarchal and absent figure is the model for all our governance.

Dear American G.I. No. 1,

I watch Post-Vietnam era action movies to be closer to you. Sites for reflection

mark what has already occurred through the persisting white/dark/white

strata seen by way of animal print. Camouflage firmly in place. Missing

in Action.

I’m asking for letters, so I can connect to how others made sense of their absent fathers. What are the father stories that were told? How did they absorb those stories into recognition of themselves personally, even politically, and then how do they revision? Talking back and questioning their fathers, saying what can no longer be silent, is an act of paying critical attention to male authority. By doing so, we learn to question all bodies that govern us, near and afar, directly and indirectly, next to you and next door to you; we wonder in quiet and out loud and directly to those entities that shape us.

Dear Floyd,

Father, all of my trouble and beauty and difficulty and love come from you. In a box of your things, I find reminders of our connection; I see your actions echoing in my life. In your friends’ memories, I get a second-hand taste of the joy you gave freely. Your humour evident in left-behind belongings and laughing tales told by those who knew you longer than I, and I find myself jealous, and sorrowing. I shared a bond with you greater than most, and yet I am the one who knew you latest and least.

Reading these activated voices, the letters I have received so far, excerpts of which have been inserted throughout this essay, I learn of our similarities—and how it is that we all have similar stories? From Kentucky to the Philippines, L.A. to New Jersey, how is it that the behaviors are the same? What are the narratives shared by our fathers that have mastered them the same? The answer to that is what hurts us all.

dear anthony lee porchia,

you said i was a redbone not high yella & that everybody has a father & these are things i keep in the back of my journal right along with bucket lists & nightmares, how the pages with your name on them seem all wa-wa-wa- & pity party when i read them back to myself, about all the times you were never around & all the times you didn’t do a thing about all those things sits on my skin like buyer beware only i had no control over what i was buying & no control over being purchased & i know that you said jesus died so that i can have everlasting life but some how that particular bible verse does not cover a multitude of all your sins.

As a woman, seeing the impact that male authority has on the daily lives of women across the globe, it is important for me to seek out my father and ask him if he can unlock, in some way, the crystal stair of “dick culture,” so we can move forward in a way that allows for better treatment and respect of women and children. Maybe together, my father and I can develop a treaty on “Let’s Not Fuck Each Other Up” with these stratifications that put us in psychosocial distress. That you, dear Gerald, are capable, in all ways necessary, to grow a child. That you, dear Gerald, have done the inner work so you are not passing along your self-hate, brokenness, arrogance, and sorrow—and then no unconditional love to balance it out, no presence to help in the healing of self, and the many selves before us. What is needed is a higher-level of thinking to get us out of the mindless, redundant narrative that male authority has assigned to us all.

Father.

Do you break?

Are you broken? Father.

Can I stop? Can I stop yet?

Is it enough?

Can I be your little Alexander?

If I climb high enough, will you watch?

Father, I can.

I assure you I can.

I will climb until you say, “my child, I am proud!”

Crush, until you smile and blow a kiss to your diligent boy;

Your loving son.

I am just waiting

on permission from you

to stop

breaking.

It is not answers I specifically desire, it is the conversation that matters. To engage and be accounted for and seen. It’s a way of stepping out of the wound and into a whole view of yourself.

Dear Whoever You Are,

. . . I need to put this matter to bed and call it a night. Whoever you are, wherever you are, know that I am doing alright. Actually, I am doing better than alright. I am married to a wonderful woman and I have a beautiful and very intelligent daughter. She is a grown woman now. You missed out on a lot. I am forever grateful someone was there to pick up the slack.

To learn more about the dear Gerald project and to submit a letter visit: http://atoguyana.wordpress.com/dear-gerald-letter-submissions/

Excerpts from letters written by Tessara Dudley, Mary Louise Hotlen, Reinette F. Jones, Jane Y. Lopez, April Lorenzo, Mg Roberts, Amoja Sumler, and Anastacia Tolbert.

Arisa White is a Cave Canem fellow, an MFA graduate from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and is the author of the chapbooks Disposition for Shininess and Post Pardon, which has been adapted into an opera. Her full-length collections Hurrah’s Nest and A Penny Saved were published in 2012, and dear Gerald was self-published in 2014. Her debut collection, Hurrah’s Nest, won the 2012 San Francisco Book Festival Award for poetry and was nominated for a 44th NAACP Image Award, the 82nd California Book Awards, and the 2013 Wheatley Book Awards. Member of the PlayGround writers’ pool, her play Frigidare was staged for the 15th Annual Best of PlayGround Festival. One of the founding editors of HER KIND, an online literary community powered by VIDA: Women in Literary Arts, Arisa has received residencies, fellowships, or scholarships from Headlands Center for the Arts, Port Townsend Writers’ Conference, Rose O’Neill Literary House, Squaw Valley Community of Writers, Hedgebrook, Atlantic Center for the Arts, Prague Summer Program, Fine Arts Work Center, and Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference. She is a 2013-14 recipient of an Investing in Artist Grant from the Center for Cultural Innovation, an advisory board member for Flying Object, and a BFA faculty member at Goddard College. Her poetry has been widely published and is featured on the recording WORD with the Jessica Jones Quartet. Arisa is a native New Yorker, living in Oakland, CA, with her wife. arisawhite.com

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)