56 pages, $8

Review by Caitlin Corrigan

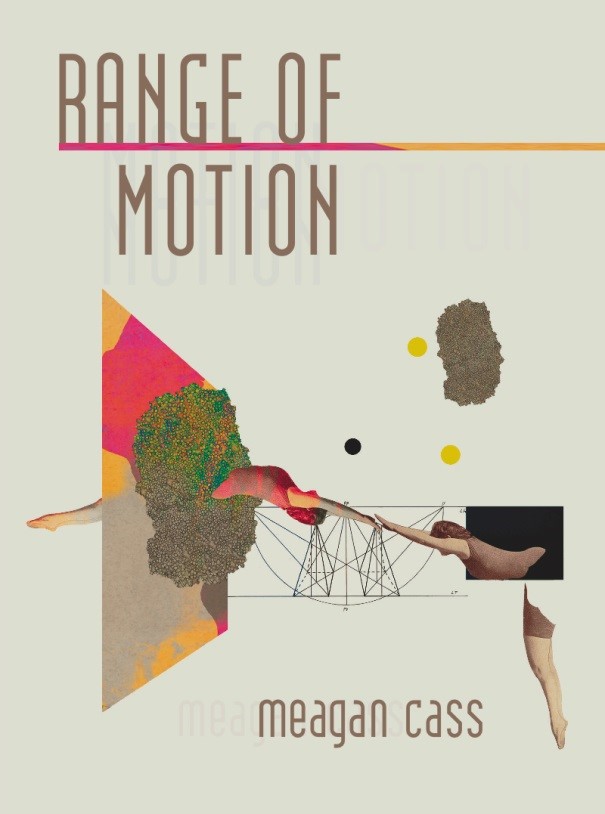

In Range of Motion, Megan Cass performs the magic trick of presenting the inner lives of an entire family with novelistic depth in less than 60 pages. Less sleight of hand and more clown car chauffer, Cass’s gift for manipulating structure and detail creates a dense, but very readable collection of linked stories.

We begin with a flash fiction after poet Craig Raine’s “A Martian Sends a Postcard Home.” In Cass’s version, the Martian is writing from a suburban summer in upstate New York, observing human rituals in all of their fleshy, sweaty glory: “They make the pilgrimage once a year, in that season when the heat blurs the trees in their yards, when they plug up their light squares with grey boxes, when they shout their language across fields that could almost be our surface, redbrown and dry.” The repeated “they” here is broad, but in the following stories, we move much closer, hovering above the more intimate rituals of a family riding the tide of their years together. Alcoholism, affairs, the unreliability of memory—these dark spirits of the American suburban psyche are all present in Cass’ debut chapbook, but there is also warmth, playfulness, and an attention to sound on the line level that elevates these stories beyond what, in lesser hands, could be mere Cheever mimicry for millennials.

Cass, an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Illinois Springfield, follows a married couple and their two children, alternating point of view to create a collaged portrait of the fractures and forgiveness that happen over the course of an entire lifetime. We first meet Ari and Sarah, the couple’s children, in the second story, “Egg Toss, August 1989.” What stands out in this piece is the seesawing between nostalgia and sharp, sensual detail. Ari remembers his sister’s birthday party as “always almost over. The pre-made burger patties have been grilled, the supermarket cake cut, the glut of white frosting smeared on paper plates.” The distancing of the past tense collides with the pure aural pleasure of the line, invoking a dissonance familiar to anyone who has dared reconsider the blurry haze of childhood from the sober light of adulthood.

Later, in “Backyard Dreams,” we learn more about the perm-patting, last-beer-drinking mother seen only peripherally at the birthday party. Rosalyn, now four years sober, her children grown, considers her husband Max’s peace offering of a hot tub. The couple has recently reconnected after an affair and Max presents the hot tub as a reminder of the fun they had on early trips as a family. Rosalyn can hardly remember the reference, but calls to mind the way Max would help Ari after a spill on his skis:

“It must have moved her to see him do this, in the parka and faded ski-pants he bought back in Buffalo, in college, when it was enough for them to cross-country flat fields, come home and make love in their rented bungalow, when they didn’t know about Killington or Mt. Snow or Jay Peak, didn’t know how lift tickets could be a kind of pretentious jewelry, displayed on jacket zippers all season long, didn’t know the ways marriage would make them unrecognizable to themselves, the ways they would betray each other, would feel like they were walking in ski boots in their own house, their movements alien, hulking, dangerous to every small, bare thing.”

The run-on sentence has a spiraling energy that brings us closer to the Rosalyn’s core, but Cass resists the temptation to keep us trapped in interiority. Instead, she exposes these two flawed partners, literally. The story ends with the couple entering the hot tub together in a moment both full of hope and also resignation to the reality of the hurts they’ve both endured: “They stare at each other, the porch light like a search light, their bodies turning hot, their faces reddening, their hair, flecked with chlorinated water, beginning to freeze, to shine.” Is this uncomfortable, sexy, or some combination of both? The characters in Range of Motion are driven to ask, in one way or another, is this how it really happened? Is this how we got to where we are today?

Finally, it must be notes that Cass’ talent for bringing the non-human voices to life seems almost unfair. She closes the collection with the strangely poignant “Portrait of My Father as a Foosball Man, 1972-2012.” This creates a bookended feeling to this chapbook—we begin with an unseen, alien observer and we end with another, and this foosball father articulates the main ache tearing at each of Cass’ characters in Range of Motion. It’s not that he’s unhappy—“ It’s just that it’s been so long since anyone turned his metal spoke heart with purpose…”

***

Caitlin Corrigan writes reviews for Necessary Fiction and The Review Review. Recent essays have appeared in English Kills Review and The Nervous Breakdown, and her fiction has appeared in NANO Fiction, Word Riot, and the Tin House “Flash Fridays” feature. Reach her at www.caitlincorrigan.com.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)