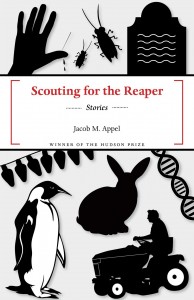

194 pages, $15.15

Review by Max Vande Vaarst

Jacob M. Appel’s Scouting for the Reaper is a masterpiece of human hysterics. In nearly each of these eight collected stories, which shift in perspective across age and gender lines, yet hold firm throughout to their essential self-seriousness, the Dundee-winning biochemist polymath Appel makes a habit of substituting obsession for conflict and the paranoiac for the poignant.

Our first encounter with Reaper’s “Dear Diary” brand of melodrama comes in equal doses through the three adolescent-narrated openers, “Choose Your Own Genetics,” “Creve Coeur” and the title story “Scouting for the Reaper.” The love interests here manifest themselves early, entering their respective scenes accompanied by hammy giveaway lines such as “He was a broad-shouldered, square-jawed teenage dreamboat…his cheeks blossomed like peonies” and “At that moment, the girl – the most alluring creature I’ve ever seen, stepped angelically into our artificial winter.”

The charming gravity these figures are made to possess is immediate and inescapable, locking Appel’s high school heroes into lustful tantrums that often overwhelm whatever half-formed adult troubles constitute the bored margins of their lives. As her parents’ marriage dissolves over questions of her paternity, self-declared science prodigy Louise can only opine, “…there was nothing so extraordinarily special about Jonah, except that at some point I’d decided to love him and only him.”

Of course, lovestruck passion is something of a default setting for teens, enough so that it is perhaps unfair to fault Appel for relying on a device as popular with Hollywood as it was with Shakespeare. The issue with Scouting for the Reaper is the extent to which neuroticism becomes the author’s fallback position, infecting even those stories containing better ideas and more mature protagonists.

In “Ad Valorem,” a recently widowed housewife descends into ferocious longing for her late husband’s accountant, using his like state of grief over the death of his own wife to rationalize her steamy CPA dreams and stalker-esque behavior. The housewife then performs a spontaneous one-eighty upon being asked on a date by the accountant, now convinced beyond the point of horror that he is nothing more than a con man and a cheat. The story maneuvers to trap her on a boat with the duplicitous accountant, presenting a rare moment of true Hitchcockian dread as she struggles between his advances and her binder of evidence, but soon enough backs off and whimpers toward a “happy” conclusion, her husband’s memory now only an apparent MacGuffin in the cellophane plot.

In “Rods and Cones,” a middle-aged librarian suffers psychosomatic seizures and paragraph-long fits of existential loathing over her pet rabbit’s unexpected bout of blindness, going as far as to request guidance and veterinary advice from both her local rabbi and a clinic called “Dr. Zhang’s Earthly Remedies.” We get the impression that, like the unemployed man’s fixation with frozen Neanderthals in Raymond Carver’s “Preservation,” this compulsion, this willful desire to embrace the trees and neglect the forest is representative of a deeper emotional paralysis.

Sure enough, Appel scatters hints of discord: another troubled matrimony followed by another halted insta-romance, this time with a “stunningly handsome” doctor. (The operating principle of Appel’s writing seems to be that if a man and a woman come to interact, they must be declared either old flames or lost-cause lovers within the sentence. I was a bit surprised that the librarian character never bothered to make a pass at her rabbi.) Despite this, the author fails by story’s end to pull back the mask of metaphor and deliver on those fears that hide beneath the skin. Whereas Carver’s quirks help explain his characters, Appel’s quirks consume them.

Too many endings opt for calamity over coherence. Too many mother figures read as vicious cardboard cutouts, popping up once every fifth page to denounce their husbands as “selfish bastard[s]” and their husbands’ former lovers as “cold-hearted bitch[es.]” One of the collection’s better stories, “The Extinction of Fairy Tales,” centers around the memory of Sammy, a submissive black gardener who, in his mysterious, unsolicited service to an elderly white folklorist adheres to the Magical Negro archetype, with a splash of Will Smith’s Bagger Vance thrown in for taste. Even the stories themselves grow repetitive. It is impossible not to recognize that “Creve Coeur” and “Scouting for the Reaper” share almost the exact same plot, albeit it for their gender reversed narrators.

The lone true winner in this collection is Appel’s final offering, “The Vermin Episode,” an imaginative retelling of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis from the perspective of Gregor Samsa’s rabbi neighbor. Here, divorced from his literary comfort zone in the over-educated American northeast, Appel is free to build upon the work of a master to discover a unique allegory for Jewish identity and the value of religious ritual. “The Vermin Episode” is, alas, the shortest of the eight stories by far.

***

Max Vande Vaarst is the founder of the quarterly arts journal Buffalo Almanack and a writer of imaginative fiction. He is currently a graduate student in American Studies at the University of Wyoming and can be found online at www.maxvandevaarst.com.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)