Spork Press

36 pages, $12

Review by Emily-Jo Hopson

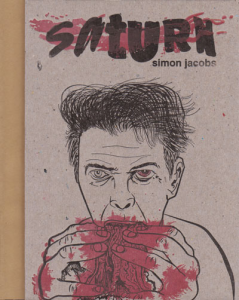

Saturn, by Simon Jacobs (of Safety Pin Review) is a brave oddity: a collection of 16 shorts about David Bowie, both semi-biographical and hyper-fictionalized. If the thought of reading a book of fan-fiction puts you off from picking it up, reconsider: It is a powerful, intelligent work, polished to the gleam in both theme and execution, at sentence and story level. Though Jacobs is clearly a Bowie fan, and Saturn is, by definition, fan-fiction, it is not a work of fan worship – the portrayal is affectionate, but not uncritical. It’s a fascinating, weird speculation on what life might perhaps be like in David Bowie Land, in David Bowie’s “sizable Manhattan apartment,” as the artist comes to the end of his multi-decade career. There are some accompanying illustrations, and these are equally honest; Bowie’s big teeth, jowls, stubble and age lines are all there.

Plot basics are open to interpretation. My reading: Having become “the ‘elder statesman’ of rock, an old man left to passively herald in the new as his voice goes reedy,” Jacobs’ Bowie is descending Mt. Olympus, and becoming mortal. He attempts to stave off the future and his mortality by revisiting and, increasingly, dwelling within his own iconography; purchased works of art begin to take on his features, flashes of Ziggy Stardust and The Thin White Duke appear in stormy windowpanes, movie and video game cameos are re-watched, obscure bit-parts re-inhabited.

In one of the collection’s starkest pieces, Bowie’s wife, Iman, asks him if he is “intent on spending the rest of his career remolding the faces of a past he’s promised time and time again to leave behind.” In “David Bowie builds the house on Little Tonshi Mountain,” the titular house turns out to be an almost-exact replica of one he had built in the late 80s. On the surface, Bowie pretends otherwise – he “acts surprised–a sharp intake of breath, a quick step backwards” for every room he unveils. “David, I’ve already seen all of this,” says Iman. Shades of the real Bowie, here; who after a heyday built and marketed on his effortless changeability, has, in his later years, begun to recycle old masterpieces, bring old costumes out of the box. In Saturn, fear is to blame.

Fear of mortality is hardly untouched territory in literature, but Jacobs weaves his particular brand of fear through almost every paragraph, with spidery skill. After a dream in which he takes the Eucharist – is a mortal man, worshipping a different god – Bowie wakes “in a sweat borne of fear.” In his nightmares, “pale, organic life teems around him,” while God – who happens to look a lot like the Thin White Duke – “presides over the scene as a ghost might, knowing his hands could no longer touch.” Reading 1001 Arabian Nights, “each gilt page he turns fills David Bowie with dread: he expects the Sultan to kill her, to tire of her guises, her artifice and her costumes.”

If Saturn has one weakness, it is simply that David Bowie is so well known to so many people. Questions of how on earth Jacobs and publisher (Spork Press) got away with it all aside, the book may suffer a little from adaptation syndrome. Jacobs’s Bowie aligns with my Bowie, but perhaps the same may not be true for the next reader; in which case, the book won’t do the icon justice, will say too much, or too little, will disappoint.

Alternatively, preconceived notions of Bowie-ness may color the reading – I myself was excited by a fleeting mention of Bowie as a “21st century man.” Swayed by the prior acquisition of trivia, I convinced myself that this was in reference to the song by Marc Bolan (of T-Rex), close friend of Bowie and glam rocker in arms, dead in ’77, preserved a ‘20th Century Boy’ forever. In hindsight, I realize that perhaps I was stretching it a tad. Be prepared for any foreknowledge you have of Bowie, his family or his contemporaries to creep in between the lines.

Jacobs is almost certainly aware of this possibility. He embraces trivia – the book itself is named for the planet dominant at Bowie’s birth. Moreover, this is a Bowie ever-conscious of the lens through which his well-observed life is viewed, of the omniscience of public perception. Friends and family are pre-fixed by journalistic epithets at all times: “his wife, Somali supermodel Iman,” “his son, BAFTA-winning filmmaker Duncan Jones.”

My own journalistic epithet: Reviewer, in love with this book.

***

Emily-Jo Hopson is a full-time copywriter and regular PANK reviewer. In March, she was awarded a Writer’s Bursary by Literature Wales for the completion of her debut novel, The Seven Lives of Esher, a glam rock retelling of the Tale of Taliesin. She blogs at http://thesomethingfishy.tumblr.com.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)