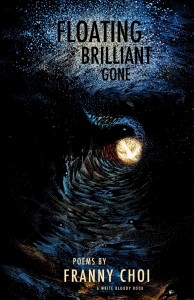

88 pages, $15

Review by Aozora Brockman

Franny Choi’s “To the Man Who Shouted ‘I Like Pork Fried Rice’ at Me on the Street” in her debut book of poems, Floating, Brilliant, Gone, is refreshing. Finally an Asian American woman is flinging back sickening truths hidden within a cat-calling man’s words, delving deeply into his subconscious and into the consumerist desires that fuel sexism and racism. What the man is really saying, the speaker reveals, is that he wants to eat her like Chinese take-out, like she’s a “…butchered girl / chopped up & cradled in Styrofoam / for [him] – candid cannibal.” In few words Choi makes us both smell the taste of human meat wafting from the plastic and feel the violence of a perverse desire that stems from the swallowing of stereotypes of Asian American women. She is, in his imagination, exotic, “brimming / with foreign;” a prostitute from the “red-light district;” and dangerous like “worms in your stomach.” By revealing specific stereotypes hidden within the man’s cat-call, Choi makes clear the fallacies of the “she was just asking for it” argument, as it is obvious that it is his uncontrollable sexual hunger and media-saturated mind that is the causal factor. But the power that is gained from illuminating the nonsense behind normalized justification is measly compared to the physical revenge Choi dishes out in the final lines, in which she is “…squirming alive / in [his] mouth / strangling [him] quiet / from the inside out.” By the time the poem is over we don’t know if we should cheer or cry—after all, the speaker’s desire to gain back her power grows so immense that she takes the man’s life. We end, therefore, with a paradox of a woman and man murdering each other, and with a looming question: where is the fine line between fighting the good fight and replicating violence?

The striving for—and fumbling with—violence and power is a central theme in Choi’s poems. Often power is conflated with love, as it is in “Orientalism (Part II),” which begins with the image of the speaker’s “…cousin and her white boyfriend / dressed as John Lennon and Yoko Ono / for Halloween…” The speaker, too, has a white boyfriend and can’t help but see her relationship through the lens of history: the white conqueror and the war-bride, “…the beating myth to his tin man chest.” Similar to the speaker in “To the Man…,” her lack of power results in a show of violence. Yet one day she looks up to see her lover with his “…lips nearly singed off,” by her words and realizes that he is trying to tell her that “Not every house is haunted.” In other words, in the same way that we cannot assume all Asian Americans are foreigners, we must not expect that all white men will take advantage of, and not question, their privilege. The poem ends with the speaker and the lover pausing at a mirror before stepping inside, both coming to terms with what others may see in them, and who they can make themselves be.

Through her poems, Choi makes us realize that it isn’t until you look yourself squarely in the mirror that you see that you too, are prone to perpetuate an entrenched power imbalance within American society. In “Gentrifier,” she coughs up the unspoken guilt of being a part of the whitening of a neighborhood. She compares herself and other new residents to “pioneers” and the original occupants to “natives,” linking the modern-day displacement to the genocide of Native Americans. She admits, “I look more like the cambodian kids against that wall / than any of my roommates. but feel safest within two miles / of an espresso machine…,” expressing the heart-wrenching reality of knowing that what you find comfort in is detrimental to others’ lives. By looking unflinchingly into the self, Choi forces us to do the same: how are we turning a blind eye to our own role in perpetuating a system that ignores the needs and rights of the 99%? Why is it so difficult to sacrifice our power and privilege? We understand through “Gentrifier” that we are not so different from the cat-calling man who ate: we are both, in some ways, ruled by our desires, which in turn feeds a corrupt hierarchal system.

These truths hurt and overwhelm. As Choi writes in “The Mantis Shrimp Speaks,” to see them all feels like, “Too many truths setting my retinas ablaze, and me mad, mad, mad at the end of it all.” But the worst we can do after our eyes have been forcibly opened is to arrive at apathy. Even so, Choi gives us permission to rest our spinning minds, ending her collection with the poem “Unwords,” in which she is “…too whirlwinded” to the point of not being able to speak. So she allows herself to accept the silence, to “sit at dawn’s feet, kiss her hem” and be flooded with “sweet nothing” in return. By ending with this piece, Choi leaves us in a space of deep reflection and meditation after a barrage of hard-hitting, emotional pieces, and shows us that it’s necessary to pause—to gather up questions and recharge—and that as long as we keep our passion and love, we can rekindle our hope and battle on.

***

Aozora Brockman studied poetry and Asian American Studies at Northwestern University. She was raised on an organic vegetable farm in Central Illinois to an American father and Japanese mother, and her work has appeared in the Split Rock Review, theCortland Review, and the Chicago Tribune.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)