51 pages in PDF form, $10

Review by Maya Lowy

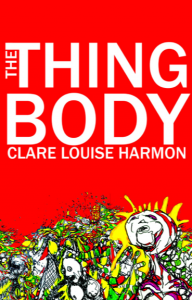

Pushcart-nominee Clare Louise Harmon’s debut collection, The Thingbody, is a kind of claustrophobic flipbook, a philosophic, psychotropic memoir. It sears your eyeballs, claws at your fingers, begs to be listened to. Ultimately, the book is more than the sum of its parts. It mosaics into a compelling peek into a burgeoning academic mind.

Forty-one pages of poems (available, for now, only in PDF: in many ways, Thingbody is a book-of-the-future) alternate between neon-bright blocks of color and postmodern blocks of text. If Gertrude Stein and James Joyce had ever had some sick, stuttering baby, it might look a little like Thingbody. Hand-drawn illustrations throughout remind us of the gruesome, homuncular, and yet somehow not indelicate body of this titular thing. “Call me Skinsack for I am the deindividuated,” Thingbody opens. “I am that which seeks violence seeks and lacks ethical privilege of person.”

Thingbody, we quickly learn, lives within our speaker/narrator, and our speaker/narrator is a woman, a violist, and an academic, who is put into treatment after a suicide attempt. Most of Thingbody, which seems to be presented chronologically, takes place in this “hospitalspace”:

Here in hospitalspace we replaceable we objects we Thingbodies wearing MediChoice gummygrip socks. For us one seventytwohourlockdown is the same as the next we of gunshot or bottleofpills or knifemarks on breasts and stomachs on hands and calves.

It would be remiss not to note that surrounding Thingbody’s launch, Harmon has been careful to be open and honest with regard to her journey of recovery from anorexia. On her website, ontologyofthus.com, she states: “I wrote down a thing that I experienced. Rape and violence and eating disorders are ugly, ugly specters. I wrote them to pacify them. To make these most grotesque things beautiful.” But this book cannot be directly claimed as a book about rape or violence or eating disorders. Harmon is not a straightforward writer, and Thingbody is not a straightforward character:

They say it’s my research that puts me in this place in thusplace hospitalspace parse inscrutable memory or rapevision or PTSD or clusterfuck horror. Find God consider Post Positivist Realism as alternative.

The woman leading us through Thingbody is not a victim. She is a reader, a thinker. She is many things: a human-animal, brute body; a philosopher. She insists on smuggling her

Fagles Odyssey Lydia Davis Proust translation Moby Dick small moleskin notebook with pen drawing of Poulenc Precarious Life Bergsonism The Soundscape The Sonic Self Maria Lugones Naomi’s book if there’s room

into the hospital. She is, I can tell early on, quite a bit smarter than I am. And she’s not afraid to show it.

At the same time, she isn’t aloof; she isn’t afraid to show her vulnerable, physical side, either. This combination of brainy bookworm and desperate, naked, barefoot body is a rare depiction of humanity in literature, a rare entwining of the abstract and concrete, the mind and the body, which all of us perplexingly contain.

That said, the text itself is often more atmospheric than meaningful, more barrage than image. Is that Postmodern, or Post Positive Realism? Don’t ask me. I can tell you that the sparsity and density of words on the page (just a few, crammed together, surrounded by color and plenty of white space) helps me skim through intimidating concepts. With a book as intense as Thingbody, layout is critical, and Harmon’s design goes a long way toward making the writing effective. Scrolling through the PDF, you feel insane, but in bite-size portions. This book feeds you that insanity, makes it almost… fun.

I’ve read Thingbody three-to-five times at this point and I still don’t feel like I can talk about it with any authority. Its texture is somehow both slippery and gritty, like slimed bricks; it gives me an image to grip (“blackplastic mug”) and then grabs it back out of my hands (“in utopia of ubiquitous time”). The scenes of violence are wrenching, the scenes of beauty poignant.

Thingbody succeeds in a gestalt fashion: born from Harmon, it has come into its own squirming living homuncular horror, and that’s beautiful in itself. Am I glad I’ve read it? Yes, wholeheartedly. Did it make me sick? A little. Did it change my life? I don’t know if I’d go that far. But I know that Clare Harmon is an author to watch, that her voice is strong and arresting and portentous of a real development in the field. I’ll assert that I believe Thingbody will be a book with historical importance. Put ten dollars into it and you’ll be thrust into someone else’s head for forty pages. And even if that someone else is, at times, intimidating and a little bit incomprehensible, she’s got a mind worth getting to know.

***

Maya Lowy was raised on the West Coast, educated on the East Coast, and is now an MFA candidate at the University of New Orleans. Her poetry can be found in Quaint Magazine, West 10th, Poems to F*ck to, The Golden Key, and other publications. Follow her on twitter at @mayalowy.

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)