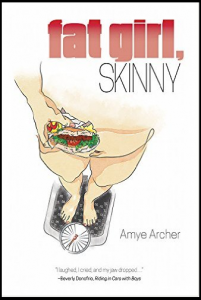

Big Table Publishing Company

January 2016

REVIEW BY EMILY PIFER

—

“Losing weight is a lot like losing your mind.”

—Amye Archer, Fat Girl, Skinny

Amye Archer has lost herself—or she’s determined to, at least the parts that weigh heavy. That is, the pounds. But losing yourself, even parts, even pounds, is a dangerous business. In Fat Girl, Skinny, we watch Archer watch Amye, her younger self—spiraling. First down, then out of control. A crime has been committed in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Her husband of two years, Jack, has been entangled with one of his coworkers. There are texts. Texts Amye finds and cannot ignore. These texts mark the final transgression of their difficult relationship. Amye was tethered to Jack by his need for her to hold him through his anxiety—to act as both witness and antidote to his disease. “I was needed, and so long as Jack needed me, he would never leave me,” she says. But Amye didn’t need Jack. Not really. “I was unhappy,” Archer tells us, “but I wasn’t ready to be without that unhappiness yet.” And so there are boxes and breakdowns. There is anger, guilt, fear. Eventually, there are divorce papers. Eventually, there is a void so wide Amye cannot see out. She nearly drowns. Maybe she did need him, because one thing is for sure, she needs something. So, Amye forks over the discounted membership fee for Weight Watchers, steps on the scale and stares at the number. 265. She writes 165 beside GOAL. Because, she figures, if she ever wants to have the life she’s always wanted—the good man, the baby, the two cars parked outside, the books of poetry, or at least a tolerable job, and not to mention the sweet revenge against Jack—she must get skinny. “Being skinny is a Utopia,” she tells us. We know Amye is going to lose—we just don’t know what.

Archer does not look away, and so neither can we. “I’m only 28, but time is growing thin in my mind,” says Amye. She is left with nothing but the losses that lay at her feet. Jack and their home, the life they built together during a relationship that spanned across his illness and her weight gain. And then her sister, Jenny—the skinny one, smart one, pretty one—moves from across the street to New York City with her boyfriend. In the midst of so much losing (the love, the life, the weight—swiftly at first as grief steals her appetite and leaves her craving cheap beer and dead-end men), Amye begins to lean. She leans on the community of courageous, frustrated women at her Weight Watchers meetings. There is a solidarity in their small talk, in the language of female bodies. The guilt and shame and envy and knowing. For Amye, there is a past marked with pain and rejection and dependency. “This is the face of food addiction. We promise, we disappoint, we eat, we feel bad, we repeat,” she says after falling into a black hole of fast food breakfast staples one morning. And so until she can stand on her own, if ever, Amye keeps leaning. Georgia, a friend since the two were five-years old, is always on the other end of the phone—or the other side of the table at the bar. They begin walking, talking—about men and marriage and desire and sick mothers, about what they will do and where they will go once their bodies are skinny. They dream in bikinis.

There are stumbles—no, there are falls. Amye joins the long tradition of intelligent women who repeatedly choose the wrong objects for their deep desire, and heavy need. She drinks. She chooses tipsy evenings that bleed into mornings over healthy, balanced meals and exercising. She is frustrated at work, but resists her creative yearnings to get back to writing poetry, or try something new entirely. As readers, we begin to feel tired, yet desperately committed—like Amye. We want to grab her by her slimming limbs and ask her how she hasn’t noticed that none of this is working. The weight is trickling off, but does it mean anything if her insides are still quaking with the trauma of repeated wounding? If a part of her is still hanging on to Jack and making it impossible for her to inhale new life? We want to ask her why she keeps seeking validation from everything outside of her body, when we’ve heard it begins inside the self. We wonder how she can’t see what we see. We’re rooting for you, Amye! we want to scream. But Archer knows our satisfaction cannot come easy. She carefully, continually reminds us of the truth about loss, about being lost. And about grief, and loneliness, and rejection—and how these states of being do not dissipate but transfer like toxic energy inside our bodies. About the self-loathing, self-hating trap that imprisons women who want to disappear—who want to be seen, but only in an entirely different body. “This is the life of someone so desperately trying to be someone else,” she says. Fat Girl, Skinny is a story about a survivor—Amye. “Things end and begin again, and people survive these breaks. And I was determined to be one of them: a survivor,” Archer says. This is the language of a battle familiar to so many women. And Archer portrays this battle with a necessary fearlessness.

Archer is relentlessly self-reflexive as she carefully layers scenes of triumph on top of scenes of struggle.

She weaves Amye’s memory with a narrative voice that is privy to a series of realizations and sources of hope that Amye has not yet found inside herself. Archer’s vivid, precise telling calls to mind a line of thinking about what and how we tell ourselves our stories—and write them into memoir. Archer’s work suggests that not only recalling, but vigilantly excavating the ways in which we have survived, which bodes well for a future of surviving.

Fat Girl, Skinny puts chronic struggle with weight and self-worth on the same plate as questions of what it means to be a woman both stuck and drifting. It does not shy away from contradiction and complication. Archer asks her readers to consider whether the life they’ve built (or fallen into) can support their weight. She wonders if there aren’t things we can lose. She begs us to take control of what and how we gain. And to look both back and forward—relentlessly. To not only see, but to try then try again to make sense. In prose that balances the precise with the ornate, Archer provides those who are struggling with a place to lean. She cracks open a conversation we need to be having about struggling with weight. Because Amye’s particular problem is particularly female, Fat Girl, Skinny is a decidedly feminist text. Archer refuses to shield our eyes from the harsh truths of what it means to be starving in a life that so often feels pre-determined by the way in which we fit into skinny jeans, by the way in which others’ gaze all but controls the ways we see ourselves, and how this reflection can become like a prison sentence. For all of these reasons, Amye cannot find her way to an existence that is completely free of body pressures and pressuring. But what Archer does with language, and with remembering and considering, is far more in harmony with reality. Amye loses the weight, but what the fuck does it mean to be skinny?

![[PANK]](http://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)