~ by Hannah Rodabaugh

86 pgs/$15.00

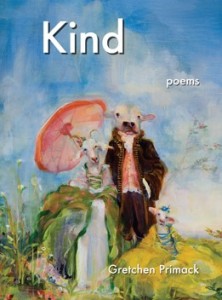

Gretchen Primack’s most recent collection of poetry, Kind (Post Traumatic Press), is protest poetry at its best and worst. At its best, it will make you think; at its worst, it will make you uncomfortable, which will also make you think. The poems, which deal primarily with the inherent dignity of different kinds of animals, will create responses as various as the poems: humility, a sense of the dignity of animals, occasional bewilderment, excitement, and even occasional anger were a few of the many emotional responses that I often felt when reading Kind. This is a compliment. It is rare to read a book of poems, and garner such a variety of emotions and range of emotions while reading it. It certainly makes for exciting reading.

A middle poem, “The Other Half of the Simile,” reiterates what are the most salient themes of this volume. An overwhelming sense of despair fronted within factory farming becomes a short epithet-heavy discussion of human involvement. She hazards:

They beat him like a dog

They packed them in like cattle

They caged them like animalsAnd why do we chafe not at the beating,

but which being

is beaten?Not the cage, but who is caged?

Why should any being be packed?

They were animals

He was a beast to herWho are the beasts?

Just from this segment, we get a sense of how deeply thought and deeply felt concern towards animals is for Primack. This is hardly surprising given her work as a political activist in the animal rights movement. But, she weaves animal rights towards understanding with deftness. Everything is intentional in the landscape of this well-structure volume. For Primack, the rights of animals are human rights, and vice versa.

“Ringling,” written from the persona of a retired circus elephant, relates what an elephant would speculate to humans if our roles were reversed. The poem starts, “Maybe someday you will trick / for me. / Maybe I will find value in you / on one foot.” One thing about her work that fascinates me is this shift in perspective. It can be complicated to use because of issues of anthropomorphism—though Primack is an excellent writer and uses anthropomorphism towards reaching awareness an audience would possibly adopt. The poem finals with the ending sentiment that reiterates this: “None of me / is left [,]” Primack as the elephant muses, “still / you found something / to waste.”

However serious these messages are, they are often interjected with lighter moments. Several poems behave like haiku with an imagistic presence of language. The following section, from “Vermont III,” illuminates a Basho-like simplicity in language:

So much rain—

it just isn’t natural.

The herons are bothered:

no luck with dinner, no

luck with lunch……the hailstones frogjump

the grass, rushing the birds

and newts inside.

This concreteness and simple lyricism was really a joy to read. Primack usually writes with a careful eye to simplicity in this book.

A different example that stuck out to me relates a germinant feeling of language. Peacefulness has become a Keats-like sensibility. In “Wrung,” she writes, “I don’t sleep, but you do—and perfectly… / Meanwhile, / a face away, the breath you have pulled up is clean / as poppies. It smells like growing.” One could almost imagine the woman as autumn by the “granary floor” from Keats’ “Ode to Autumn” in the language. It is pure simplicity at its heart, but it works well in Kind. Able language is such a treat to read by someone who knows how to use it.

One theme that takes precedence involves the pattern towards small personality we are guilty of in judgment of others, and which we present as a dominant view of animals’ personalities. Humans’ lives are often smaller than we view them; animals’ lives are often treated the same way. Another poem, “Matter,” begins with the stanza:

What if you were tiny:

A bit. A mote. What if

you were a grain, a green

grain waiting.

What if a fish

mattered as much as you

matter—if you do.

Blake wrote similarly of human lives in his poem “The Fly.” This needs one admonition. While Blake necessitates the hopeless comparison between human and fly, Primack seems to go a step further and creates a world where such comparisons are rhetorical, intentional arguments: this process highlights animals’ lives and not just the lives of humans in comparison.

In “Mother II,” Primack believes that we wrongly contrast mothering between humans and animals. She writes:

Only humans mother. Only we

care for our babies. Everything

else spits out young. Thank god

you’re here, they say, please

rid me of my children.

While forceful, it gets the point across well, and in a way that was emotionally revelatory for me to read. It seems simple to say, but Primack often speaks about animals’ lives from a perspective we may have not considered.

Primack loves animals and she writes about them with a passion and intensity that few could do. While other nature-based poetry may touch upon the full, emotional lives of animals, Kind is rarer in its language precision towards the topic, and it’s simple and enjoyable. These poems will be wonderful for you if animal rights are important to you. “I want this to become something else, / somewhere kind” (67) she writes about the world of animal welfare. We should agree.

***

Hannah Rodabaugh received her MA from Miami University and her MFA from Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School. Recently, her work has been published in Defenestration, Used Furniture Review, Palimpsest, and Similar:Peaks::. She has work forthcoming in Horse Less Press Review, Nerve Lantern, and Open Letters Monthly. She currently lives in Boise, ID, where she is teaches at Boise State.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)