~by J. Capó Crucet

http://jadedibisproductions.com/

Paperback: $15.00

iPad App: $4.99

Fine Art Limited Edition Snow Globe: $8,500

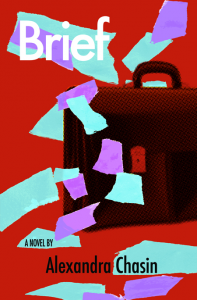

I have a confession to make: I don’t own an iPad, and so I’m not the target audience for the original format of Alexandra Chasin’s Brief. (The iPad, we’re told in a note from the publisher that opens the book, is “the device for which [the text] was specifically written.”) I also don’t make the kind of bank to afford the $8500 limited edition fine art snow globe version (which features a fake Warhol and has “a tiny print copy” of the book buried in its wooden base). That left me with the monochromatic paperback option, tried and true but, as the book’s opening note warns, somewhat limited: part of the experience of the app version is that it randomly splatters images (and snippets of images) in and around the novel’s text in an effort to “evoke the novel’s time period and storyline, probing the role of cause and effect in history.” The paperback version is just “a snapshot of the app,” and with that intro, it’s hard not to feel like you’ve chosen wrong for picking paper over plastic (or whatever iPads are made of).

Bells and whistles aside, the story itself is told from the point of view of ungendered Inqui, an art vandal on trial for defacing a modern art masterpiece. Structurally, it takes the form of a monologue directed at Your Honor—you, the reader—as Inqui makes a plea for mercy. As evidence, Inqui traces the history of art vandalism, trying (along with the unrelated images that interrupt and displace the text) to convince us that Inqui’s crime was inevitable by evoking history and culture, both broad and intimate. Inqui begins at the literal beginning, giving us their whole history-tangled story from before birth:

“The nightly news of the day coursed through the amniotic fluid that surrounded me. Powers was charged with espionage. I got organs. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison. I got arms and legs”

The digressions and lectures that follow tend to circle around (and back) to Winnie, a neighbor born on the same day as Inqui, a sort of twin in Inqui’s thought experiment about the role of history and culture in their lives. Winnie suffers a worse fate, and that fate has in part led Inqui to this courtroom, though the narrative seems reluctant to play up the humanistic aspect of their friendship/romance, choosing instead to stick to the premise for which the format of the book itself is trying to argue.

In an interview at 3 Quarks Daily, Chasin said, “If app-ness itself is a slap in the face of the Literature lover, then there’s one resonance with art vandalism.” While the images are intended to be a manifestation of the questions/premise raised by Inqui and the text, purportedly influencing or manipulating our various readings of Inqui’s defense—each image (at least as was intended with the iPad version) a random accident, much like the things that went into forming Inqui (or so the text argues)—they have, I suspect, less of an impact in the print version. After a few pages, the judge/reader finds themselves just reading around them, though maybe that’s part of the point: image as obstacle. It’s easier to ignore them on the page than on a screen, which might be saying something about the ways print books will manage to survive in the digital age.

But the premise finds its way into the prose, too, which is at times rollicking and super-saturated with snippets of pop culture and advertising butted up right next to philosophy and high art. Inqui’s rants flip and turn and smash these phrases together, the sonic similarities between them being the primary way they’re linked: “Fetuses everywhere scream – you scream, I scream, we all scream — for a large screen.” When Inqui delves into cliché, it’s with the intention of pointing out how we’ve come to accept banal language on a daily basis, and it’s represented with effective and disturbing accuracy.

Brief’s Seattle-based publisher, Jaded Ibis Press, “researches and publishes narratives that represent a continuum of literary history and the future of narrative arts – from the concept of clay tablets and illuminated manuscripts (history) to interactive and brain computer interfaces (future).” It’s an ambitious and rational approach to the way the digitization of books (and book-like objects) will continue to impact reading and publishing. Releasing Brief as it was originally intended by Chasin—as an iPad app—was a brilliant concept, even if Brief as a paperback left me wishing for an iPad.

***

J. Capó Crucet is the author of How to Leave Hialeah, which won the Iowa Short Fiction Award and some other stuff. Stories and reviews have appeared in The PEN/O. Henry Prize Anthology, The Rumpus, Guernica, Ploughshares, Virginia Quarterly Review, The L Magazine, and other places. On Twitter: @crucet.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)