~by Sherrie Flick

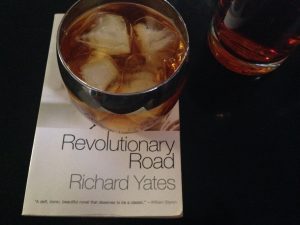

This month at Eat Drink Book, I stir and shake Richard Yates’ novel Revolutionary Road.*

Published in 1961 but set in 1955, Revolutionary Road gives witness to the burgeoning, now clichéd and reproduced on coasters, dish towels, fridge magnets, and televisions shows, 1950’s suburban culture.

As the novel unfolds, we crawl into Frank and April Wheeler’s relationship and watch it fester and boil behind their pristine picture window. Frank Wheeler–perhaps the best ever written anti-hero–drinks, his wife April drinks, his co-workers drink, his mistress, their friends, their real estate agent, everyone—everyone—drinks in this book. And they seem to, amazingly, hold their liquor.

Yates himself was no stranger to drinking, and this might be why the drinking itself, although present and obvious when you dig, is also seamlessly tucked into the narrative—like a compulsion—an omni-present antidote for the Age of Anxiety.

Part I follows four days of Frank Wheeler’s life, starting Friday with the Laurel Players abysmal production of The Petrified Forest through to Monday, Frank’s 30th birthday.

Friday night Frank and April have a full-blown fight driving home from the catastrophic performance. April sleeps on the couch, and Frank closes himself into their bedroom “drinking until four in the morning, methodically scratching his scalp with both hands, convinced sleep was out of the question.” He wakes Saturday morning to see “the first fly of the season … crawling up the inside of a whiskey glass that stood on the floor beside a nearly empty bottle (35)”. The perfect visual description of the hangover about to come.

Saturday doesn’t go so well. April still won’t speak to Frank. Her silence builds into Sunday where he is “heavy with beer” and looking forward to a visit from their neighbors, the Campbells (59). Usually on these evenings “with the pouring of second and third drinks they could begin to see themselves as members of an embattled, dwindling intellectual underground” (61).

Tonight is different for the foursome, however. They’ve come ashore deep in the suburbs, unable to talk themselves out to sea. Frank grows anxious. “There was nothing for him to do but get up and collect the glasses and retreat to the kitchen, where he petulantly wrenched and banged at the ice tray (69)”. He’s drunk; he knows it. Frank turns 30 on Monday, and he loathes himself for saying it seems like the end of an era.

Frank is a war veteran, and in the novel it’s only during times when he remembers his service, has a deliberate plan of action, that he has purpose. Otherwise, Frank fumbles forward in fits and starts through this new, shiny world with clean kitchens and smartly seamed pants, practicing his pensive looks and sexy walk.

Another failed evening and Frank heads into the city Monday morning. He talks with his hungover cube-mate Jack Ordway, notices the secretary Maureen Grub, and decides—why not—to get together with her. He contrives some filing that makes for a late lunch and calls for “round after round of drinks” at the restaurant (100). This leaves Maureen feeling a bit out of focus. After lunch they end up at her place. She asks him up for a drink, actually. They have sex, and Frank’s feeling back on top of the world. So much so that he needs out. And with a quick “You’re swell” he’s “down the stairs and out on the street and walking; before he’d gone half a block he had broken into an exultant run, and he ran all the way to Fifth Avenue….He felt like a man” (106).

Frank catches the late train home, where his luck has seemingly changed. Not only is April speaking to him, she hands him “an Old Fashioned glass full of ice and whiskey” (108). There’s a birthday cake and presents and a scene of exultant American normalcy.

After Frank cold showers Maureen off, he comes out “feeling like a million bucks” (112). April sets “a bottle of brandy and two glasses on the night table” (112). She proposes they move to France where real intellectuals live. She’ll work and he can spend time thinking, intellectualizing.

Since we aren’t in April’s point of view here, we can’t know what her real intentions are, but her plan frightens Frank. It makes him glimpse for an instant how he postures through his world. But like a good drunk, he soon falls prey to the fantasy of it. “After a minute he found it easy to stay awake, if only for the pleasure of sitting with her under the double cloak of a blanket, sipping brandy in the moonlight and hearing the rise and fall of her voice” (113).

They have a plan. Frank takes a last big sip “letting it burn the roof of his mouth and send out waves of warmth across his shoulders and spine…” (120). The plan is in the future, nothing Frank needs to worry about now.

They stay up all night talking about their escape. Dawn rises and they fall “asleep like children” (122), waiting for their hangovers to settle in, again.

*Yates, Richard. Revolutionary Road, Vintage Contemporaries, NY, 1961.

***

Sherrie Flick is author of the novel Reconsidering Happiness and the flash fiction chapbook I Call This Flirting. She lives in Pittsburgh.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)