$24.95/256 pgs

Review by Denton Loving

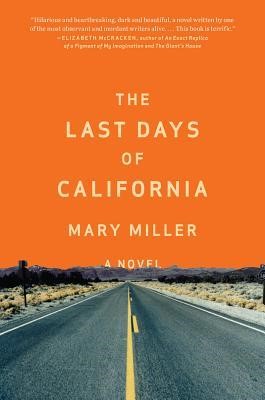

Short story writer Mary Miller (Big World, 2009) makes the transition to the long form in her debut novel, The Last Days of California. In this novel, the last days refer to the last three days of life on Earth before the Rapture. Fifteen year old Jess, the daughter of a fundamentalist Christian family from Alabama, narrates this tale. When a prophet named Marshall predicts the end of the world, Jess’s father feels assured that their family (Jess, her sister Elise, their father and mother) are among the chosen who will disappear from the Earth and be rewarded with eternity in Heaven. The family embarks on a road trip to California, where, because of time zones, calculations show the Rapture will end. Jess’s father wants to be in California, so the family can, ostensibly, spread the word of the Rapture and save some souls in the final days—before it’s too late. The purpose of the trip is juxtaposed by the family’s careless spending and even more so by the adventures the sisters have in the evenings at the various hotels where the travelers stay on the journey.

In what could easily be viewed as the road trip from Hell—rather than to Heaven—these four family members are forced to examine their religious beliefs, as well as their relationships with each other and their views of themselves. Like all good fictional families, this one is complicated. The father has lost his job prior to their trip to California, and details suggest that sudden losses of employment are a frequent occurrence. He is also diabetic but chooses not to follow a diabetic diet since he plans to be raptured before it matters. The older daughter, Elise, doesn’t follow the family’s religious beliefs and is openly hostile to the rest of the family. Jess is the only person who knows Elise’s biggest secret: she is pregnant. Their mother, who has given up Catholicism for her husband’s fundamentalism, is struggling to hold the family together.

Jess’s life is complicated even without taking the end of the world into account. Her image of herself is depressing. She’s sure boys don’t like her and never will. Her closest friend is one of convenience. Faced with what may or may not be the end of days, Jess is changing her ideas about God, religion, her family and how her life is and will be shaped:

Elise had already decided God didn’t exist and she was okay with it. I wanted to go back to the time when I hadn’t thought about whether or not I believed,when I’d gone to church and Sunday school and passed out tracts and it never occurred to me to question any of it. Now everything was in question, all at once, and it mattered.

If The Last Days of California is a narrative of a pilgrimage, it’s unique in that it’s a 21st century, red-white-and-blue-all-American pilgrimage of excess and empty-calories that sometimes feels like a travelogue of gas stations and fast food cuisine of the southern states: “We all liked Wendy’s, except for Elise, who only liked Burger King because they had a veggie burger, but their fries were bad. Their onion rings were decent but the portions meager, even if you got a Large.” While these passages—and they are numerous—speak to a certain inane quality pervasive in American popular culture, as well as to the manner in which minutia become important in long periods of time in enclosed spaces—such as a road trip—commentary about why tacos at Taco Bell are better than burgers at Burger King often feel unimportant and awkward. It should be noted that part of this awkwardness speaks to the difficulty of writing about modern life with a literary frame of mind. Miller’s attempt to examine American culture, when every human action seems to be punctuated by product names and brand merchandising, is admirable.

More significantly, however, passages about processed food preferences deflect from what Miller does well, which is when she mines the inner depths of young Jess’s teenage mind coming of age. Of particular note are the scenes detailing Jess’s first negotiations with boys. The sexual experiences that occur in these brief relationships are by no means titillating. Rather, what’s interesting is seeing Jess learn and process how boys react to her. It’s watching Jess navigate these boys that keeps the reader reading with brief insights such as this one: “I didn’t have to be perfect—hardly anyone was perfect. Why did I think I had to be perfect all the time?”

In these scenes, Miller’s experience and expertise as a short story writer is showcased through her economy of language and choice of detail:

He opened the passenger-side door and I climbed in. It smelled like gasoline. I ducked into the back and sat on a mattress covered with a burnt-orange blanket. It was quiet for the few moments it took him to walk around and unlock his door, and I wondered what I was doing. I knew he wouldn’t hurt me, but this was the kind of situation I had always been taught to avoid. It was risky behavior, how bad things happened.

It’s easier to take big risks when faced with the end of the world, but in this case, it’s the end of the world that leads to the beginning of new lives for these characters. “I wanted my life to be different and better,” Jess tells herself, “but I wanted to be the one responsible for changing it.” By the end of this story, readers will feel confident in Jess’s ability to do just that.

***

Denton Loving lives near the historic Cumberland Gap, where Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia converge. He serves as executive editor of drafthorse: the literary journal of work and no work. His writing has appeared in Cosmos, Literal Latte, Main Street Rag and in numerous anthologies. Follow him on twitter @DentonLoving.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)