~by Dan Pinkerton

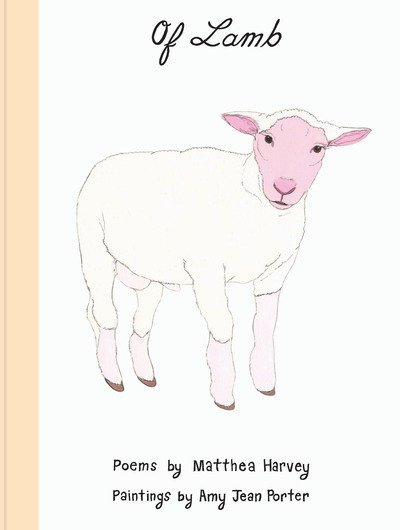

Of Lamb, by Matthea Harvey, paintings by Amy Jean Porter

McSweeney’s Books

Many of the classics have an air of weirdness about them, novelty coupled with discomfiture. The art startles, making you more alert, opening you to a new kind of beauty. Think Dalí or Buñuel, Wallace Stevens or William Faulkner, Bladerunner or Charlie Kaufman. Of course there’s bad weird, weirdness for its own sake, genuine insanity. Such weirdness quickly fades. But there’s also good weird, the weird that endures. Of Lamb, a book of poems by Matthea Harvey with paintings by Amy Jean Porter, is assuredly good weird.

The weirdness is there in neon from the start. Porter’s paintings are a hodgepodge of color and line, stencil-style patterns, leaves and limbs and vines spiraling across the page. We get glimpses of everything from Manny Ramirez to Seventies-era split-levels to Washington crossing the Delaware. In one illustration, the book’s protagonist, Lamb, stands on a table gnawing at his back leg, surrounded by cacti, while a large wasp settles on his haunch. In another, Lamb is tightrope walking above an old cabinet-style TV set on which an image of Peter Jennings plays.

Throughout Of Lamb we get these layers of image and meaning and tone. There’s a psychedelic Alice in Wonderland quality to the pages, the way different time periods overlap, the way Lamb changes color, the way the mythological and mundane intersect. Of Lamb is not just weird; it’s trippy. And I mean that as a good thing.

Each page can be viewed as an individual image-poem, but the pages also link to form a narrative, the story of a life lived—in this case the lives of Mary and Lamb. There’s the obvious and intentional connection to the school rhyme, but, as Harvey points out in her afterward [spoiler alert], the text is also pieced together from the book A Portrait of Charles Lamb, which chronicles the life of Charles Lamb and his sister Mary. The author wisely waits until the end to describe her source material and erasure process. I’m better off knowing, but it’s a little bit like seeing behind the curtain. Some of the wonderful strangeness disappears.

The story starts and ends with Lamb, a very pensive and well-spoken, uh, lamb. His personality is such that—as with literary cousins Charlotte the spider, Pooh Bear, Fantastic Mr. Fox, even the FX channel’s Wilfred—we soon enough forget he’s not human. Of course when Wilfred’s not waxing philosophical, he’s sniffing butts, and Lamb, “one of the listeners” who “moved among the rouged illusions of dawn,” also occasionally chomps on a nettle or yearns for the nearest farm field. Whereas Wilfred’s primal impulses are played for laughs, Lamb’s imply a more existential struggle.

The early Lamb takes in the world like a child does when he first encounters Mary, in jeans and sneakers, “crying in the hedge,” both characters painted blue to evoke an air of shared sadness. They find they are kindred spirits, both of them “unbalanced” and “high-strung,” both of them undomesticated. Though “bound together,” they stand apart from others, watching the “thronging crowds.” Here we get a strong sense of adolescent awkwardness, pimply isolation, a craving for connection.

The bond that forms between Lamb and Mary goes sideways, gets creepy, with some bestial undertones. “Lamb felt unusual next to Mary,” Harvey writes, and in the accompanying image we see the two sharing an embrace. Later, “They pin’d and hungr’d after bodily joy.” The painting shows them standing apart from one another with somber expressions, yet cherubs smile overhead in an image and text reminiscent of William Blake. While we’re thinking of Blake, we’re also recalling James Dickey’s “The Sheep Child.” This is a symptom of good weird, the ability to take references from various eras, toss them in a blender, and come up with a palatable puree. I’m thinking of how Tarantino turns Danny Zuko into an aging junkie hitman doing the twist with Uma Thurman in Pulp Fiction, or how in Twin Peaks David Lynch combines Fifties-style pop and coffee at the Double R with Canadian brothels and dreams of murder victims speaking backwards in red rooms. The artifacts Tarantino and Lynch incorporate into their films serve as signposts back to reality. Harvey and Porter manage the same thing in Of Lamb, using various eras, references, and subtexts to give the book more body, more bouquet.

Lamb and Mary meet “in whatever room happened to be closest” and become “intertwined.” Mary indulges in “animal satisfactions” while Lamb in turn begins walking upright, calling himself “half a man.” He struggles with the contradiction between his animal and human selves. While Mary’s features morph, growing lamb-like, Lamb becomes increasingly articulate. As time passes, both Lamb and Mary come to sacrifice their urges, cautioning against pleasure, which leads to sadness, remorse, a feeling their world is shrinking.

Lamb manages to root out his contradictions. He comes to enjoy smoking, wearing slippers, gazing at his reflection. He is “dandified and amusing, often invited out to dinner.” Mary isn’t so fortunate. She secludes herself, falling into a funk, and it is at this point the story turns yet again with its reference to the “snake in the temple garden.” It seems the two are not undone by their initial carnal urges but by later consuming the forbidden fruit. Contemplation and knowledge are what injure them. When Lamb is old and fat, he is left with his memories, which paradoxically he has trouble remembering.

As you’ve no doubt gathered by this point, there’s a lot going on in Of Lamb. It’s a shifting, heartfelt, and ultimately sad book. I’ve already called it weird and trippy, so I may as well go so far as to say it’s deep—deep as in layers of substrata. In short, it’s not for kids. Or maybe it is. In her blurb, Rae Armantrout calls it an “adult-children’s” book, which is apt and true and speaks to the book’s ability to transcend genre. Regardless, I doubt I’ll share Of Lamb with my kids until they grow a little older, not that there’s anything graphic or objectionable in it I don’t want them to see. Maybe the opposite: there’s too much I’m afraid they’d miss, because Of Lamb is a book that demands repeat viewings, like all the best stories and paintings and films that seem at first bewildering, maybe even disconcerting, but draw us to them again and again.

***

Dan Pinkerton lives in Des Moines, Iowa with his wife and two kids, both of whom have strong opinions about what constitutes great literature. His stories and poems have appeared in such places as Quarterly West, Hayden’s Ferry Review, New Orleans Review, Subtropics, Sonora Review, Boston Review, and the Best New American Voices anthology.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)