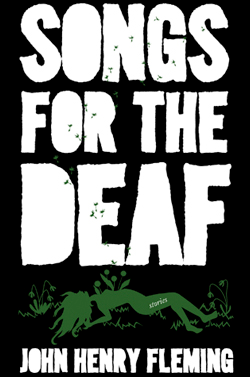

Burrow Press

172 pages, $15

Review by Thomas Michael Duncan

For one reason or another, so much short fiction is preoccupied with everyday people. Perhaps because ordinary, relatable characters are the quickest and easiest way to connect with readers. Of course, quickest and easiest are not synonyms for best.

The characters in John Henry Fleming’s stories are not ordinary. Take the father in “Chomolungma.” When a crisis threatens to tear his family apart, the man of the house takes drastic measures. Or maybe “drastic” isn’t the right word. “Insane” might be a better descriptor. He orchestrates a leisurely family outing to the peak of Mount Everest. But with the family strapped for cash, he can only afford “discount Sherpas” who “can’t even tie their own shoelaces.” A lack of physical conditioning, proper equipment and provisions, bone-chilling walks along shaky ladders spanning deadly chasms—these perilous obstacles are mole hills to this man. The basic idea is noble, to unite the family by working together to reach a common goal. But the father pits his family against an unconquerable opponent, dooming them from the start. His wife and son succumb to delirium, and his daughter begins an ill-fated romance with one of the young, cheap Sherpas.

The family survives longer than logic would allow, but by this point in the book readers will be ready to forfeit their disbelief. Through earlier stories they will have already encountered a girl who hovers above the ground and a nomad who can read the future in clouds. Comparatively, a family of four surviving in one of the harshest environments on the planet is no stretch of the imagination.

Fleming’s peculiar characters often mean well but wind up being punished for it. The cloud reader, for one, finds himself persecuted for refusing to break his own moral code. Young Antonio, of the title story, woos an entire town with his magnificent singing voice, yet he’s infuriated when he fails to entertain a young deaf girl. Foolishly persistent, he continues to sing for her, refuses to believe that anyone could be immune to his God-given talent.

“The Day of Our Lord’s Triumph” is laid out like an ancient scripture (and annotated with “marginal notes for children”), only the “Lord” of this story is a teenage boy, and his great miracle is winning a pickup game of basketball.

“The chill rain did fall, yet Our Lord received the weather as His due gift. He juked His Sworn Enemies into sprawling positions on the wet concrete and brought laughter to the mouths of the Manifold Witnesses. He played the wind and calculated the effects of the rain on His shots, as the storm spoke in harmony with Our Lord’s passion.

This is how Our Lord did persevere.”

Fleming is atop his game with this story. This is the least-conventional narrative he gives us, as well as the funniest, which is a hard-won accolade in this collection. Fleming finds room for humor in every piece. There are even jokes to be found in “Coward,” a story about an emotionally damaged young veteran. On page one, his father holds a knife to his throat. On page two, he loses his gig as a radio DJ for his college station for being too risqué and the campus paper runs this headline: “Report: Panties Up All Over Campus.”

The way Fleming juxtaposes humor with affliction is part of what makes Songs for the Deaf so enjoyable. Rather than detracting from one another, the comedy and tragedy are amplified. This happens within stories, but also through the collection’s arrangement, with heartbreaking stories standing side-by-side with laugh fests.

There is no such thing as normal in Songs for the Deaf. The outrageous is standard, the unusual expected. And why should it be any other way? After all, is the idea of “normal” anything other than a agreed-upon fallacy? By the end of these stories, readers might pleasantly surprised to discover just how much they identify with these odd characters. But they shouldn’t be surprised. We’re all odd.

***

Thomas Michael Duncan lives and writes in upstate New York. His fiction has appeared in Necessary Fiction and Little Fiction, among other places. His website is tmdwrites.tumblr.com.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)