Unbound Content

125 pp/ $16

Review by Brian Fanelli

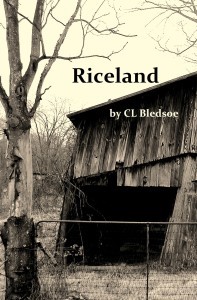

Since the financial crash of 2008 and the recession that followed, much attention has been given to industrial cities like Scranton and Youngstown, places whose economic problems are exacerbated in hard times. In CL Bledsoe’s latest collection of poems, Riceland, the author draws attention to another part of America that extends beyond the rust belt—the American farmland, in particular the Arkansas farm where the poet was raised. Bledsoe’s latest effort is an odyssey through childhood and adolescence, and it is a fine study of working-class themes, family dynamics, and the loss of small, family-run farms.

We are introduced to the father of the family in the opening poem “Roaches,” when the speaker confesses that Dad “worked long hours/and stayed drunk,” while the son too knew the pains of farm labor because he “came in from the rice fields/too sweaty to sleep but too tired not to.” Among the conflicts in the house, including the father’s bouts with alcoholism and the mother’s disease, the son tries to find beauty, and in the case of the opening poem, he listens to nature, more specifically to roaches singing. The poem ends with the image of him crawling into bed, pressing his face against the wall, listening for the roach songs. This desire for beauty, for an escape from daily struggles, is a theme throughout much of the book, and Bledsoe lays it out well, as early as the opening pages.

There is also a mixing of life and death that is a key part of the farm life, and throughout much of the book, the son tries to make sense of it, sometimes reacting against it, not wanting to be the hunter, fish-skinner, and butcher that his father is. In “Feeding the Fish,” the son recounts images of watching his father raise and feed the fish, his dad’s back strong “like the arc/of a sledgehammer,” as he dribbled food into the water “like sand pouring/through his rusted hands,” while the fish trailed “like children/until winter/when they lay fat/and we dragged our nets.” It is clear immediately that the son realizes the power his father has over the farm animals, how he has the ability to give and take life, and that death is necessary to keep the farm running.

Other poems recount the son trying to fulfill his father’s notions of manhood. In “The Old Ways,” for instance, the son recalls coming home from school and seeing a dead calf hanging. While the father instructs the son how to properly cut meat, all the son can do is listen, while trying to be as strong as his brother and father. The son wants acceptance, even though it’s clear that he is far more sensitive to life and death:

When we went inside—

My father shining like a knife blade—

I went into the bathroom, locked the door

And puked it all out.

The father does not come across as one-dimensional, however. At times, the father shows a real tenderness for his son, and he resembles the dad in Robert Hayden’s poem “Those Winter Sundays,” or the father in much of Theodore Roethke’s work: a man who is hardworking but shows his care and love, though not verbally.

In the poem “First Seizure,” for instance, after the son drinks so much that he is rushed to the hospital, the reader witnesses a change in the father. The son recounts in the second stanza:

My father, too worried to fight, remained silent,

even though he’d been the one to find me

in the dark quiet of night, shuddering, my mouth

filling with vomit. Still half-drunk from the night

before, he’d grabbed a towel, saved me

from choking in my sleep and woken

my brother to drive me to the hospital, this man

who didn’t even believe in using aspirin.

The poem concludes with the lines, “My father, who I’d never/seen ask for help with anything, ran ahead/to find a doctor, a nurse, anyone.”

In another poem, “Farmer’s Tan,” the reader encounters what years of hard farm work does to a man, how it wears the body down, how even the strongest person, such as the father, succumbs to tired muscles and sagging skin. The son describes his father’s skin as “fragile,” “falling down to his black toenails, ruined by rice field water,” before admitting in the final lines, “This man, this stone pillar who could break me/as easily as glass in a child’s hands/has been worn down by water over the years.” These other aspects of the father, specifically the poems that show glimpses of his tenderness, or how labor wore him done, are a nice change from the collection’s earlier depictions of the man as non-emotive, concerned only with farm work.

Much of the book centers around the son and father, but the mother and brother are also essential to the family. Some of the most interesting poems also focus on the small town, such as “The Boys” and “James Earl Ray,” which recall young white boys mocking Martin Luther King Jr. or hanging confederate flags from pick-up trucks and stalking and fighting black kids. These poems are some of the most startling in the book, and I would have enjoyed more of them.

Collectively, the poems in Riceland build a fine arc, a strong coming-of-age story, and Bledsoe’s techniques as a fiction writer shine through in his poetry, especially the use of voice and character. The narrative form suits this collection because, like a short story collection or novel, the reader is able to witnesses the characters change and grow, especially the young son, who ultimately reaches a deeper appreciation for his family and the farm.

***

Brian Fanelli’s poetry has been nominated twice for a Pushcart Prize and the Working Class Studies Association’s Tillie Olsen Creative Writing Award. His work has been published by the Los Angeles Times, World Literature Today, Portland Review, SLAB, Red Rock Review, and other publications. He is the author of the chapbook Front Man (Big Table Publishing) and the full-length collection All That Remains (Unbound Content). He teaches English full-time at Lackawanna College.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)