Books for Precocious Kids and Big-hearted Grownups

by Dan Pinkerton

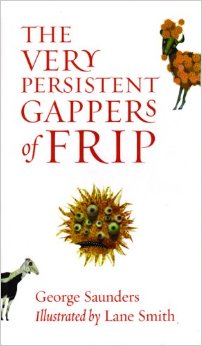

The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip

by George Saunders

There’s nothing even remotely formulaic about George Saunders. The style and tone of his stories are so distinct they become instantly identifiable, fundamentally Saundersy. Even the author’s lone children’s book, The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip, shares some DNA with his adult stuff. The book has been tamed to achieve a PG rating—no clubbed raccoons dumped into pits, just some squabbling, some light roughhousing, a little sand in the underwear—but the other elements are there: the amusing dialogue; the slangy, pared-down diction; a world similar but not quite like ours; a protagonist who manages to see beyond the limiting factors of her existence. At 84 pages, including some full-page illustrations by Lane Smith (The Stinky Cheese Man, The True Story of the Three Little Pigs, James and the Giant Peach), Gappers even resembles Saunders’ other works in length. One might consider it a starter course in Saunders.

The story is set in Frip, which can scarcely be called a town, lacking anything by way of stores, schools, or other amenities. It’s more like a three family collective wedged between sea and swamp where the families subsist by raising goats. All would be well and good were it not for the gappers: small, round, spiky creatures who crawl from the ocean, attaching themselves in large numbers to every goat they can find. Why? Because Gappers love goats. Encountering one elicits from them high-pitched shrieks of pleasure. For goats, the feeling is not mutual, and the animals stop producing milk, a major concern in a one-industry town. Saunders sets all this up neatly, economically, in the opening pages.

The town’s children (all five of them) spend their waking hours brushing gappers from the goats, collecting the creatures in sacks, and dumping them back into the ocean from whence they came. If this were one of Saunders’ grown-up tales, the gappers would likely be tossed on a bonfire, their shrieks of pleasure turning to cries of pain. But then the story would be over by page thirteen. Cruelty never occurs to the kids here. They go on gapper-brushing for hours on end, an exhausting way to spend one’s childhood. This is simply how it’s always been.

Many of Saunders’ characters share a shrugging acceptance of their fates, whether trapped in CivilWarLand or Spiderhead or Frip. Though the families in Gapper do relocate their houses progressively deeper into the swamp, trying to flee the gappers, no one but Capable, the book’s aptly-named heroine, considers actually moving to a different, gapper-free town. Things don’t always end happily for Saunders’ grown-up protagonists, who are variously ditched by spouses, canned by corrupt bosses, or just killed, but Capable perseveres, even when the gapper situation seems insurmountable.

For instead of glomming in equal numbers to the town’s various goats, the gappers start focusing their efforts on those nearest the ocean, which are, of course, Capable’s. She can’t hope to de-gapper the goats herself, and her father (crippled by grief over his wife’s death) is no help, so Capable must entreat her neighbors, the Romos and Ronsens. But they’re so thrilled to be free of the gappers they can’t bear to be dragged back into any gapper-related turmoil.

Luckily Capable is endowed with clear-eyed focus, sort of a diminutive Neo in this grade-school version of The Matrix (minus the martial arts, human-harvesting machines, and Laurence Fishburne’s cryptic aphorisms). She’s able to see and do what the rest of the herd cannot. “Just because a lot of people are saying the same thing loudly over and over, doesn’t mean it’s true,” Capable recalls her mother saying. So while the others exhaust their savings by moving their houses farther into the swamp, Capable sells her goats and takes up fishing.

Initially our heroine is criticized for her decision, told that fishing is unladylike and that girls should merely stand around looking graceful. But once the other characters glimpse Capable’s success, they ask her to teach them how to fish (so maybe there is an aphorism here, something about giving a man a fish…), which she does after some hesitation. The townspeople take up angling and the goatless gappers adjust the focus of their affections, making Frip “what it is today: a seaside town known for its relatively happy fisherpeople and its bright orange shrieking fences.”

Overall Gappers is a pleasant read, not as funny as Saunders’ other stuff but also not as dark. We care for Capable’s plight but can’t become overly invested in it since her main adversaries are harmless slug-starfish-Furby amalgamations. The absence of Capable’s mother (or the Romo boys’ father, for that matter) might prompt questions from inquisitive young readers, but otherwise there’s nothing objectionable here.

There is, though, a curious political subtext running through the book, beginning and ending with the Ronsens. In refusing Capable’s plea for help, they attribute their own good luck (i.e. the momentary absence of gappers) to hard work and assert that Capable deserves her misfortune because of some perceived lack of effort. Later the Ronsens thank God for “giving us whatever trait we have that keeps us so free of gappers.” And when Bea Romo complains to Carol Ronsen that her boys are too tired from collecting gappers to practice their singing, Carol remarks that the boys might be happier if they merely accepted their lot in life. Conservatives are sometimes accused of such behavior: blaming victims, engendering Social Darwinism, using religion to divide and categorize.

I’m not arguing such criticisms one way or the other, I just found it odd to stumble across them in a book for grade-schoolers. Maybe the political content is for the benefit of the parents reading along at home? Because I’m not sure the subtlety of these ideas is going to sink in with the Pokemon set. Maybe it’s an effort to inculcate children, to reach them before any conservative dogma has become ingrained. Coming as it does midway through the book, however, it doesn’t seem integrated with the rest of the story. We’re talking about goats and gappers and sad fathers, and suddenly we’re in the terra nova of an Animal Farm-style allegory.

By reading Gappers, we get a better sense of Saunders’ strengths and shortcomings as an author. Here he’s a bit constrained by his audience. It’s not that Saunders is ever particularly graphic (though he can be grimly, gruesomely violent), it’s just that he’s at his best when his settings and themes are bleakest. Only then can Saunders’ stories thrive from the contrast between his dark futuristic visions and his brilliant wit. Also absent from Gappers is Saunders’ recurring preoccupation with consumer culture, his funny/phony brand names, his glassy-eyed characters wandering around a world where everything has been trademarked and co-opted. Very little consumption actually occurs in Gappers. While there’s mention of currency, the only time money changes hands is when the townspeople hire movers to lug their houses deeper into the swamp and when Capable exchanges her goats for fishing tackle. What’s intriguing is that these characters, so removed from consumer culture, seem just as depressed as (for instance) the 400-pound CEO from Saunders’ first story collection. So is there any great message we might come away with after reading The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip? Maybe just this: de-gappering your life is hard but worthwhile in the end.

***

Dan Pinkerton lives in Des Moines, Iowa with his wife and two kids, both of whom have strong opinions about what constitutes great literature. His stories and poems have appeared in such places as Quarterly West, Hayden’s Ferry Review, New Orleans Review, Subtropics, Sonora Review, Boston Review, and the Best New American Voices anthology.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)