Braddock Avenue Books

304 pages, $16

Review by Jody Hobbs Hesler

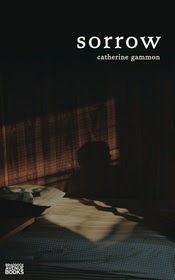

Catherine Gammon’s Sorrow is an unapologetically dark book. In this case, you can almost judge the book by its cover, which shows slants of waning sunlight, a silhouette, and a fraction of a bed surrounded by darker and darker darkness. This is not a book for the faint of heart.

In her acknowledgments, Gammon reveals that she has structured her epilogue as Dostoevsky structured the epilogue to Crime and Punishment, and the flavor Sorrow conjures is the flavor I remember from a long-ago unit on existential literature in AP English my senior year of high school. Gammon nails the sense of epic despair to the point of despondency.

Beginning by wandering through the dreams of fellow tenants of a New York City apartment building, Sorrow plumbs the special loneliness, repression, and anguish of this handful of characters, focusing most narrowly on Anita. In her twenties and working an office job by day, Anita shares a small apartment with her mother. Her mother and the neighbors – Cruz, Tomas, and Magda – each in their own way recognize Anita’s need to be helped and watched over. All also appear to be aware that she sometimes sneaks out at night and has sex with strangers in alleys. Anita’s character attempts to balance naïvete and destructive forces: “These were her selves …: The weeper. The stone face. The killer. And more.”

Early on, after a series of hallucinatory ideations, Anita kills her mother. The act seems inevitable to Anita, predicated on repeated compulsive delusions and an illogical repugnance at her mother’s monotonous existence – always watching TV and drinking beer. Anita behaves with premeditation, sharpening all the knives in the house over time before the event, and then she cleans the crime scene and goes out into the night, creating a social encounter that will afford her both an alibi and an orchestrated moment to “discover” her mother’s murdered body.

After her mother’s death, Anita’s horrific history of molestation unscrolls. She has survived abuse at the hands of male relatives of three generations, continually and repeatedly since her infancy. Her mother had taken Anita away from the rest of their family – a few brothers, a sister (the whistleblower), and Anita’s father – and continued to pay one of the brothers to stay away, all in order to protect her. As soon as the mother is dead, though, the brother comes back. Incidents of childhood molestation and then of the renewed incestuous relationship between Anita and her brother are revealed in intensely graphic detail. (See note in first paragraph: not for the faint of heart.)

The question, “What is true?” repeats throughout the work, referring to the crime as well as to the molestations, and it is a question that is never fully answered. Regardless, whatever assortment of incestuous incidents actually did happen to Anita, her losses and injuries are thorough and profound.

The most powerful moments in this book are the scenes with Officer Booker and, later, Anita’s sense of belonging when she finally winds up in jail. Booker suspects Anita almost right away, while her neighbor friends choose to think differently. Interviewing the apartment’s superintendent, Mr. Cruz, who had been something of a mentor to Anita as a child, Officer Booker presses him to say “Anything. The Truth. How you remember her when she first moved in here. How she inspires such loyalty. Why you care for her as if she were a member of your own family…Things like that.” Booker’s terse, direct dialog captures his character well and offers moments of certainty within the fabric of more dreamlike sequences.

In jail, most other inmates “saw [Anita] as one of themselves . . . She found allies.” After the fraught life that has landed Anita in jail, even this convoluted sense of community seems to contain the seeds of hope.

***

Jody Hobbs Hesler’s work has appeared or is forthcoming in Steel Toe Review, Stealing Time: A Literary Magazine for Parents, Valpariaso Fiction Review, Prime Number, Pearl, Potato Eyes Journal, Leaf Garden Press, Charlottesville Family Magazine, A Short Ride: Remembering Barry Hannah, and some prize anthologies. Visit jodyhobbshesler.com for more.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)