BlazeVOX Books

77 pages, $18.00

Review by Anne Champion

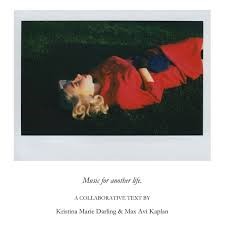

Kristina Marie Darling, already an accomplished poet in her own right (she’s published sixteen poetry collections), has begun paving a new trail with her foray into collaborative writing. Her previous collaborations work alongside poet Carol Guess, but her newest work, Music for another life, collaborates with the accomplished visual artist and scholar, Max Avi Kaplan, and the finished product is a brilliant and moving piece of art. The cover, featuring a Marilyn Monroe look-a-like donned in Jacqueline Kennedy inspired attire, chillingly depicts a woman laying in grass in a corpse pose, and this image foreshadows what’s to come: stunning, delicate beauty that adheres to societal standards juxtaposed with hauntingly devastating realities.

The narrative, composed solely of short prose poems, follows a speaker named Adelle as she traverses her lavish landscape in heels, swanky sunglasses, and pencil skirts. Each page features a different picture of Adelle—either standing outside of her domestic sphere or lounging in nature. The work of light and shadow in these photographs speaks volumes to the Adelle’s search for self and inability to find it, either from being blinded, outshined, or blurred into unrecognizablity. Some of the poses only vary slightly, so you can flip through the pictures quickly and watch Adelle move as if she were an animation. Regardless of the various ways you can look at and interpret the images, the most important thing they do is immerse the reader in a very real and detailed world: paired with the poetry, it’s hard not to empathize with the character while also feeling as trapped and suffocated as she does, despite the fact that she clearly frolics in an upper class status. Maybe even because of it.

A major theme surfacing in the poems is that of façade and distraction. In “Adelle Speaks of History,” the speaker recalls the courtship of her mother and father:

“… hair teased up, her red dress ironed and starched, every fingernail pressed firmly into place… That night, he looked right through me, toward the television set. I’m so many women doing laundry in the off hours.”

The poignancy in the details comes from the irony: women go to extreme lengths to be noticed, but what lengths must they go to in order to retain that attention? Eventually, the fake nails fall off, and even repressing them won’t change the speaker’s fate: in catching a man, she resigns herself to the job of many women before her. She must become the invisible force that makes a man’s home his castle, and once she’s unnoticed, other distractions fill her lover’s attentions, just as she once did.

Kaplan and Darling also play with common stereotypes and images of women. While Kaplan’s model looks as if she just walked off the set of Mad Men, Darling’s lines witness the dangers that clichés have for women. In “In the Midst of Disaster, Adelle Keeps Quoting Hamlet,” the speaker states:

“You’ve never seen me lost in thought, but who said housewives can’t be smart? I’m still the leading lady, a magnificent heroine strapped to the train tracks.”

In utilizing the familiar stereotype that a pretty girl can’t be smart alongside the recognizable image of a woman strapped to tracks waiting for someone to rescue her, readers can clearly witness Adelle’s suffering and loneliness. She’s suffocated by her beauty, silenced by what beauty demands her to be, and her life and sanity is most at risk from the expectation that she remain helpless. Even if her “hero” does whisk her away, he can’t save her from drowning in the weight and solitude of her unshared thoughts.

In fact, Kaplan and Darling critique the pressure of gender roles for both sexes. In “Accoutrements,” Adelle says:

“Tonight I’ll walk the pristine white beach and before long my nylons will be torn. But every landscape needs some imperfection. Men still offer to buy my jewelry as you watch from your Cadillac.”

If “every landscape needs imperfection,” the imperfection in this imagery seems to be Adelle herself, not her torn nylons. Adelle can’t fit the expectation of immaculate perfection that society demands of a housewife, and thus she’s a dark contrast to the white beach she walks along in its pristine, natural purity. The other blot on this landscape is the “you” of this poem, which the reader recognizes as a revolting show of wealth and status, a way of seeing his wife as a possession of his that other men should desire, envy, and barter for.

But nonconformity, unfortunately, comes with punishment, and Adelle experiences that pain frequently in this collection. In “Are You a Magnificent Bird or a Small Child?” Adelle reveals that she knew she would never stay married, favoring instead a single life filled with lavish parties and socializing:

“I knew I’d never stay married because I didn’t want to be married…Until finally the day arrived and the doorbell rang. When I opened the door, there was no one there.”

Chillingly, Adelle acknowledges that the cost for not conforming to societal standards is loneliness and becoming a damaged social leper rather than being allowed to revel in her freedom once the marriage fails.

The collection features an afterward of poems and pictures in which Adelle’s hair color changes and she’s submerged in a pool. Our speaker clearly transforms, but it’s unclear if the images allude to rebirth or drowning. The stoic face of the speaker doesn’t seem hopeful, and neither does the desperation within the titles. Unfortunately, the illness of the world in which Adelle was submerged creates damage of unspeakable caliber, offering bleak hope for a way out or for any sort of growth.

***

Anne Champion is the author of Reluctant Mistress (Gold Wake Press, 2013). Her poems appear in Verse Daily, The Pinch, Pank Magazine, The Comstock Review, Thrush Poetry Journal, and elsewhere. She received an Academy of American Poet’s Prize, a Barbara Deming grant, and Pushcart Prize nominations. She holds an MFA from Emerson College.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)