PANK’s Books We Can’t Quit series reviews books that are at least ten years old and have shadowed and shaded, infected and influenced, struck and stuck with us ever since we first read them.

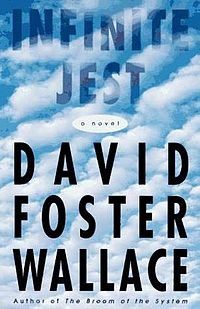

Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace, 1996

1079 pages, $18

Review by Joseph Michael Owens

I submit that Infinite Jest fans have gotten a kind of rap. Whether good or bad, deserved or undeserved, the rap’s derivation remains up for debate. What’s clear though is that I.J. is most certainly not for everyone: hating the book does not make you an inferior reader, incapable of understanding its brilliance, a douche, a simpleton, a minimalist fanboy/girl, etc. Likewise, at least in my humble opinion, loving the book does not make you a hipster, pretentious, a “snoot,” a lit snob, a douche, and/or a postmodern meta maximalist fanboy/girl etc. et al. &c. […]

Infinite Jest is ultimately a book I can’t quit, though I should probably mention up front that it’s not like I’ve tried or have ever had any real ambition to change this. Every reader has a book like this; a book that, for some inexplicable and intangible reasons, sinks its hooks into you in a way that few others can. It resonates with the fibrous strings of your core being. When you read your unquittable book, harmonies synchronize; connections are orchestrated between the page’s ink, the room’s light travelling at 299,792,458 m/s, and the relationship between your retina and the dilation of your pupils; neurons fire across pathways in your brain and . . . something happens.

You inhabit the words of another writer.

Those words often sound like your words in your voice rattling around the recesses of your grey matter and you “get it.” You’re reading a writer who is speaking directly to you, through you, using your own corporeal faculties as the means of his/her transmission.

At the very least, that’s what happens when I read Infinite Jest.

People can be put off by tiny typefaces, sections alternating between all caps and regular caps, obnoxiously long paragraphs, a decentralized cast of main characters, and, perhaps especially, footnotes. Dear god, those 388 footnotes. . . . Yet when all of these elements are present in a single book that tops out at 1,079 pages, you’ve potentially got a recipe for some serious tome-sized loathing.

But when I read this book, it sounds like a conversation that’s already happening inside my head, only a bit smarter. The random stream-of-consciousness bits, the free associations, the digressive footnotes that run on for pages at a time — all of that is what it’s like to be inside my mind at any given moment. Admittedly, n.b., I suffer from severe ADD, so that’s likely the cause of my sheer inability to focus, but it’s possibly also the reason I enjoy the book so much. When DFW digresses, my mind is usually about to wander off somewhere else too!

So much in this book, while written back in 1997, is prescient and timely even for 2014. For example, DFW did a pretty good job of predicting the hipster as s/he is commonly known today, but also digging into the root of what it might mean:

It’s of some interest that the lively arts of the millennial U.S.A. treat anhedonia and internal emptiness as hip and cool. It’s maybe the vestiges of the Romantic glorification of Weltschmerz, which means world-weariness or hip ennui. Maybe it’s the fact that most of the arts here are produced by world-weary and sophisticated older people and then consumed by younger people who not only consume art but study it for clues on how to be cool . . . It’s more like peer-hunger. No? . . . Once we’ve hit this age, we will now give or take anything, wear any mask, to fit, be part-of, not be Alone, we young. The U.S. arts are our guide to inclusion. A how-to. We are shown how to fashion masks of ennui and jaded irony at a young age where the face is fictile enough to assume the shape of whatever it wears.

DFW famously said, “Fiction’s about what it is to be a fucking human being,” and that we write to feel less alone. I know those sentiments are true for me. Writing helps. With everything. Writing is responsible for some of the most significant and wonderfully complex relationships in my life. Infinite Jest is responsible for showing me how to connect to and shape the world around me and bend its light to project through my own literary lens — even if it’s different and strange and unorthodox — to break “rules” that constrain imagination, and, perhaps most importantly, to always explore what I can do with my words as well as my stories, to connect to other people. To feel, as DFW stressed, less alone.

***

Joseph Michael Owens is the author of the story/essay collection Shenanigans! (Grey Sparrow Press, 2012), and has written for [PANK], The Rumpus, HTML Giant, Specter, Bartleby Snopes, Sundog Lit, The Houston Literary Review, and others. He lives in Omaha with four dogs, one wife, and a son.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)