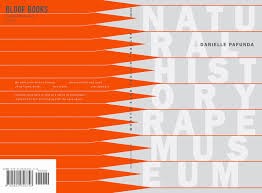

80 pages/$15.00

Review by Anne Champion

Poets get to take great liberties when it comes to language: they play with sound and meaning. Good poets will relish the way their carefully chosen words will take on new connotations next to other words and images. There are only a few words that don’t slip and shift in a poem, and one of those words is “rape.”

Danielle Pafunda’s fifth poetry collection, Natural History Rape Museum, boldly interrogates this word, graphically turning it over for inspection with dirty fingers and bloodshot eyes. In using the word rape, the title casts a long shadow over the rest of the collection. Even cradled between words like natural, history, and museum, the word always finds its meaning with the speed and violence of a gunshot wound. Despite cultural confusion and political debates over the rape and policy, the word holds only one meaning for most women readers, and that meaning is bound up in fear, anger, disgust, and violence. In Pafunda’s blurbs, many readers likened her to Sylvia Plath, and I would have to agree. While Pafunda’s voice is undoubtedly new, fresh, and evocative, the feelings of rage and destruction that these explosive poems leave in their wake are as visceral as those from a Plath poem.

The book is divided into several sections, each embracing its own set of formal constraints. In the first section, the poems are interrupted by their titles which appear in the middle of the page in a box. In another section, the poems are untitled prose poems. Another section looks at a series of animals and objects as totems for the speaker’s suffering. The final section culminates as a series of linked essays on the subject of pain. All sections are unified through their tension between the speaker and the man referred to only as “the fuckwad.”

The collection begins with a stunning opening line: “When they called my vagina. When they called themselves screwed.” The poem’s title, “I hated myself in your womb from conception,” harkens to creation, and the rest of the poem carries the haunting connotations of creation mythology, albeit in a warped, horrific sort of beginning. The poem ends with the lines:

All my long life they every day loved me

by sticking their fingers into my pudge.

While imagery of the womb and motherhood generally carry comforting and maternal subtexts, the speaker of this poem implies frightening truths in her associations. This poem suggests that from the beginning, women are reduced, labeled, given expectations, and the most menacing expectation is the prospect that our bodies are made for prodding. This truth is one women carry their whole lives, dangled over their heads in a storm cloud of fear.

The forms of these first few poems embody mystery, intrigue, and brutality. The titles literally disrupt the lines of the poems in square boxes, and this interruption signals an invasive act of violence, a demand for a space that is not theirs to inhabit. Often, the lines are uneven and disjointed, expressing disarray and a feeling of the inability to be whole, even, or pleasant in the lack of symmetry. Furthermore, much of the language reads like baby talk or gibberish. For instance: “The man in your life will exercise his fink till it wail.” This sort of language requires extra work on the part of the reader, and much of meaning comes through associations made by the word choice, images, and sounds. But this meaning never comes easily, and it often seems nonsensical and illogical, much like trying to make meaning of the act of rape. At the same time, however, this strange claptrap of language gives words to the unutterable and the abject.

In one poem, “When you lie down you get up again and there are fleas as well as bedbugs,” this language culminates in more violent and dark insinuations:

Dog the wolf with teeth from the junker.

Dog the wolf with heedful of pace.

Wolfing up on the rag rug, filed to its singular risk.

When I first read this poem, I had no clue what it meant, but it is animalistic, reduced, helpless, predatory, dirty, infested. The poem read like a dark nursery rhyme, similar to Plath’s haunting cadences in “Daddy.” While I didn’t fully understand the narrative, I read its threats and impressions easily.

My favorite section of the collection features a series of Ode-like poems to various objects and animals. Here is an excerpt from “Wolf Spider”:

Unsacked rice fret into light,

slog pot with your grizzled feel.

Once you had a fine excuse

for a lover. You slammed-gut

swollen sack of piggy laters.

And another excerpt from “Fly”:

Make thousands of eyes at your prey.

Land with digits, carry your own

syrup with you. Trim

multicolored friction, wave

each of your larvae

on to better things.

Like all the poems, this sequence features a rich language play. When read aloud, the words come out as if you’re eating a meal gluttonously and sloppily: they slip and slide on the tongue; they cough and curse in guttural and angry interruptions. All the objects chosen for contemplation are examined through a lens packed with all sorts of surprising sexual imagery and violence. And most of the animals chosen for meditation are predatory or repulsive animals, often abusive or parasitic. However, the most surprising feature of the poems is their ability to make the wretched begin to carry a sort of haunting or nightmarish beauty, as seen with the excerpt in “The Fly” above. The sweetness of syrup, the aesthetic beauty of a multicolored friction of larvae, and the hope for “better things” all take the garishness of the poems to a new and complex dimension. Yet, these poems are not without their threat and anger. In “Stingray,” the speaker accusingly asserts: “Do not think your occupation/so small it doesn’t somehow/commit to the horror.” In this book, all of nature is culpable.

Natural History Rape Museum is a haunted house, a horror show, a gruesome and chilling collection of fear, packed with images of violence, death, and the body.

In an interview about the book, Pafunda stated: “It feels good to conduct the world’s violence on the page. It’s my response to violence without doing or incurring much violence. It’s how I navigate through it.” It’s a successful navigation and interrogation of pain, a collection that is easily as difficult to digest as it is to forget. It’s major triumph in feminist poetry at a time when rape culture is as frightening and threatening in its politics as ever.

***

Anne Champion is the author of Reluctant Mistress (Gold Wake Press, 2013). Her poems appear in Verse Daily, The Pinch, Pank Magazine, The Comstock Review, Thrush Poetry Journal, and elsewhere. She received an Academy of American Poet’s Prize, a Barbara Deming grant, and Pushcart Prize nominations. She holds an MFA from Emerson College.

![[PANK]](https://pankmagazine.com/wp-content/themes/pank/assets/images/pank-logo-large.png)